The Brain and Long Covid

2 new studies shed light on persistent neuro-inflammation from even mild infections

Ever since the UK Biobank study that showed brain atrophy, loss of grey matter, and cognitive decline in about 400 people who had Covid compared with matched controls, via baseline (pre-Covid) and subsequent (~3 years later) MRI scans, there has been significant worry about the impact this virus has on the brain. Two new studies, both from researchers in Germany, illuminate the mechanisms for inflammation of brain tissue which is persistent and occurs even in patients with a mild Covid illness. Importantly, these were studies of people with Covid, not specifically individuals who were suffering from Long Covid.

The Munich Study

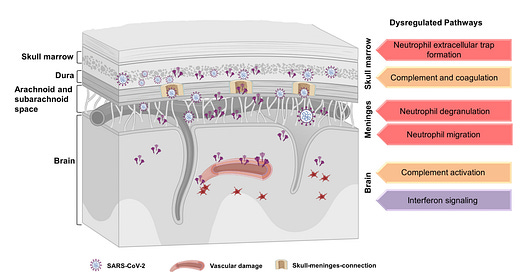

Newer insights in the past decade about inflammation and the brain have pointed to the borders of the brain—the skull bone marrow-meninges axis—as a niche reservoir that can drive the process. This is where a high density of circulating immune cells reside, patrolling the brain tissue via skull microchannels and lymphatic tissue.

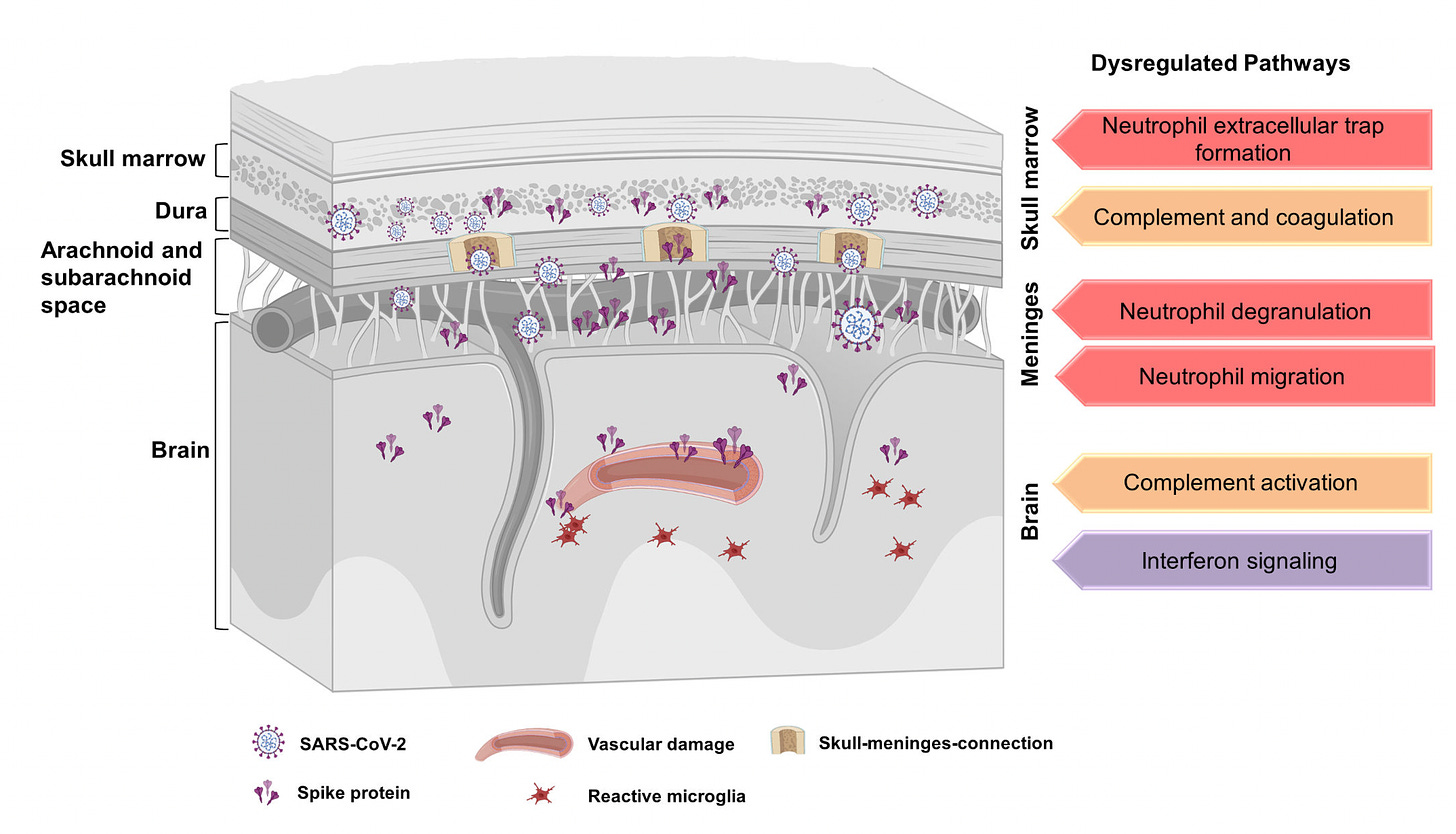

In a comprehensive imaging and omics study of mice and humans, the skull, brain and meninges, along with the vertebra and pelvis bones, were assessed from 20 patients who had died from non-Covid causes but had previously documented Covid. Long after their Covid infection (some but not enough details are available in the supplemental material), most (12 of 20) of these individuals had marked accumulation of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in the skull-meninges and brain tissue, not found in controls. Only the spike protein, not other parts of the virus, was found in brain parenchyma. In the mouse model, when the spike protein was injected, there was brain cell injury, death and persistent inflammation. As opposed to the other bones and marrow assessed in both humans and mice, there was a differential inflammatory picture in the skull, reflecting the importance of this immunologic niche reservoir.

Ali Erturk, the senior author of this study (in preprint form) summarized their findings in this twitter post. (SMC-skull-meninges connection that harbors the spike protein.)

Below in red is the staining for antibody to the spike protein demonstrating its extensive presence in one of the individuals with prior Covid, and absence in a control (lower panel). Accordingly, the persistent presence of the spike protein itself may be considered pro-inflammatory for the brain. Of note, this work cannot be misconstrued to relate to Covid vaccines, a theoretical issue that would need to be separately explored.

The Hamburg Study

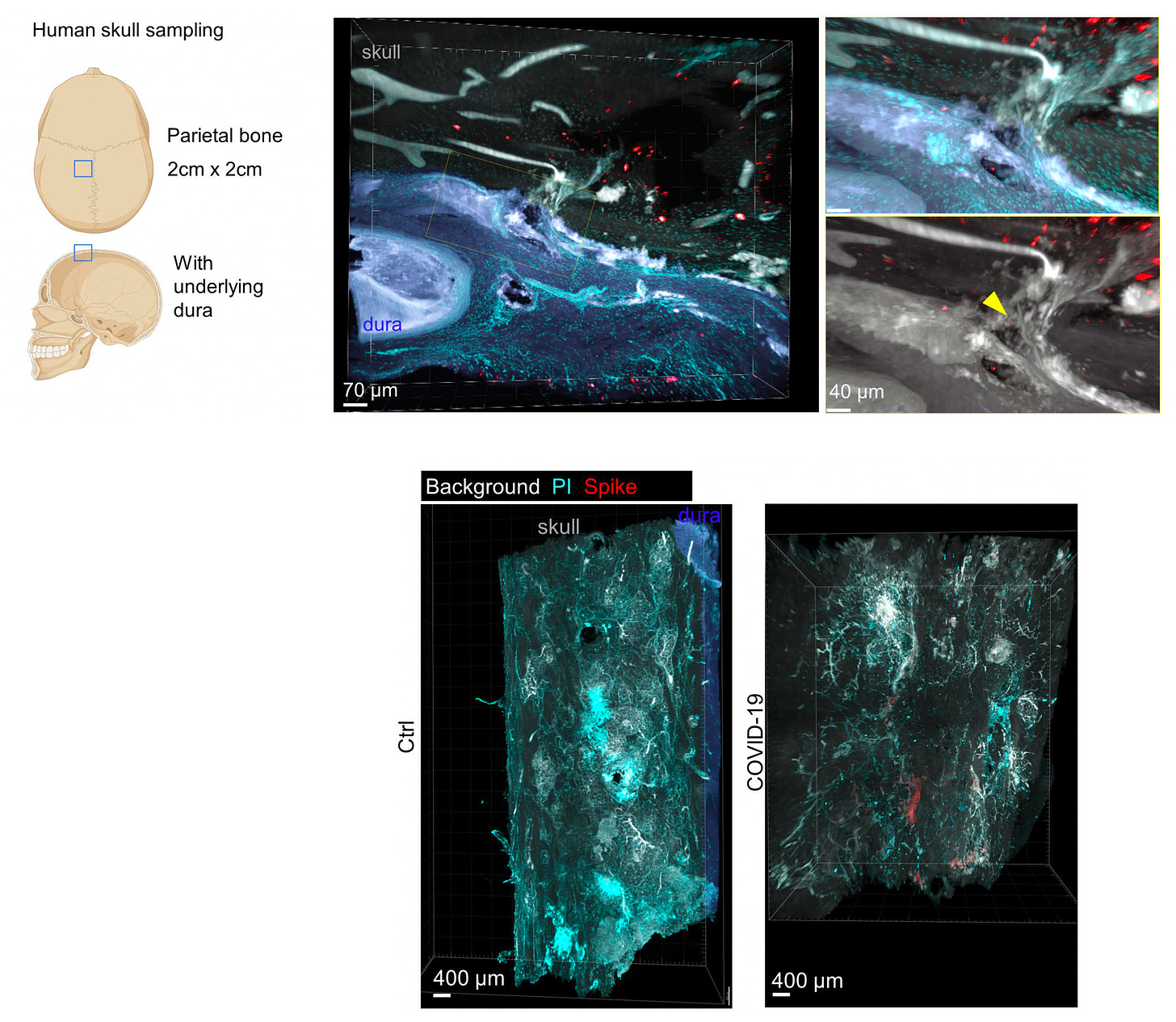

A very different study of the impact of mild to moderate Covid was undertaken by the Hamburg group, using comprehensive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess 11 different metrics (abbreviations below and correlations with histology, pathology) in 223 unvaccinated people who had Covid compared with 223 controls with no evidence of Covid infections.

Unlike the UK Biobank study, which was mostly in patients who had moderate Covid (15 patients were hospitalized in that report), 56% had only mild Covid. The images were obtained at about 10 months after Covid and the principal MRI findings were related to two important brain white matter neuro-inflammatory markers—-extracellular free water (FW above) and mean diffusivity (MD).

There were no differences in neuropsychiatric scores, including lack of evidence of worse cognitive function. The MRI inflammatory marker abnormalities were so pronounced that machine learning could accurately differentiate which scans were from the Covid patients vs the control group, as shown below. Unlike the UK Biobank study, there was no evidence of cortical atrophy.

To underscore, all of the participants of this study were unvaccinated, which takes out the potential confounder impact of Covid vaccines. There are ample studies to tell us that vaccination helps protect against Long Covid, such as the prospective one published this week, which also confirmed the risk of reinfection for subsequent Long Covid.

Contextualizing these Reports

As pointed out at the top of this piece these 2 studies did not select for patients with Long Covid. Their findings of brain inflammation were independent of symptoms, and in many cases, as previously documented, the central nervous system process develops asymptomatically. Overall, however, there are many prior studies that correlate the presence and magnitude of inflammation (via cerebrospinal fluid or blood markers) with Long Covid neurologic symptoms such as brain fog, memory loss, cognitive impairment, and sleep disorder, as summarized in the graphic and accompanying article below.

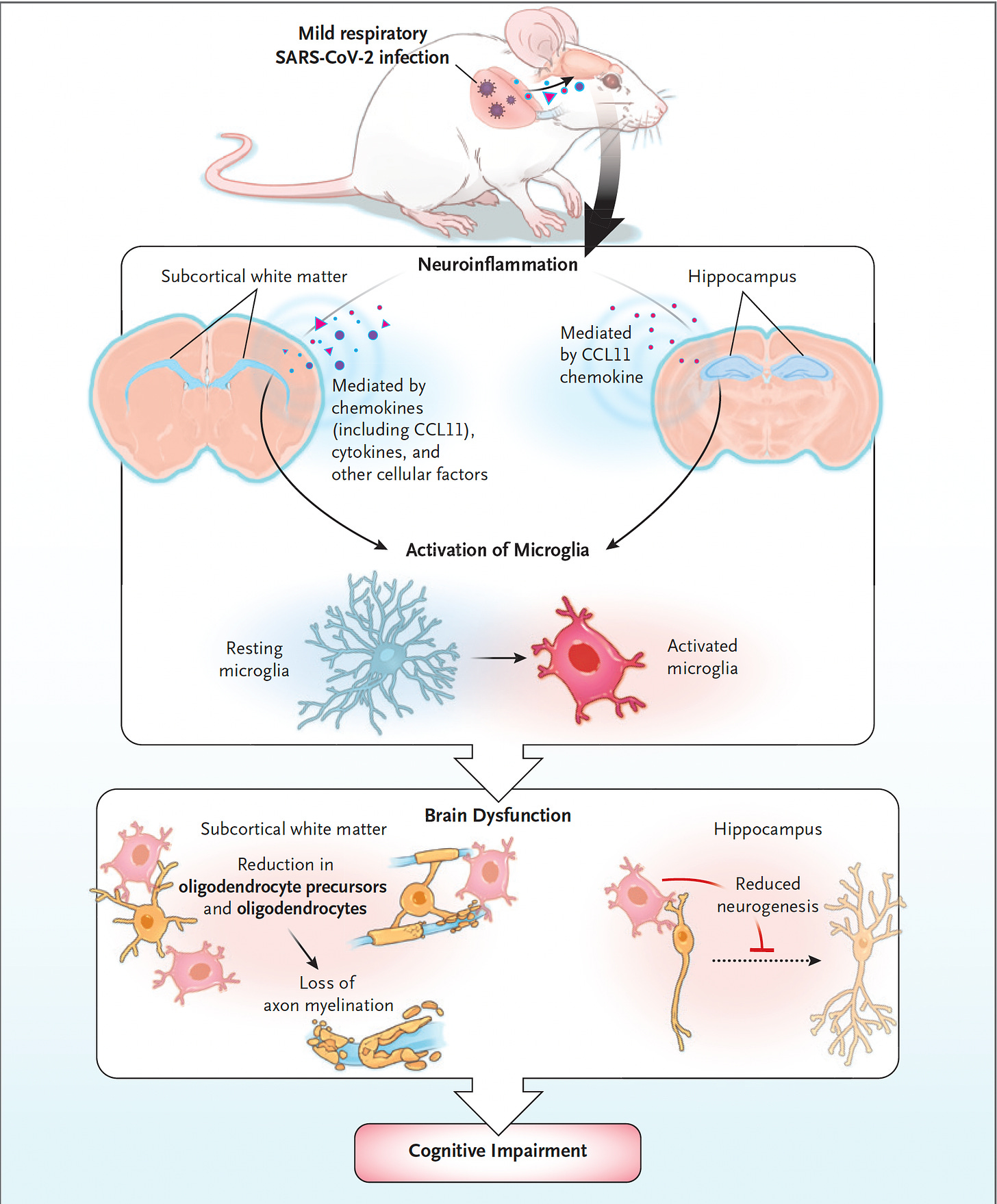

Multiple neuronal cell types in the brain are involved, as established in animal models of mild Covid. Chief among them are the microglia, the macrophage resident cells of the central nervous system, which transition to an active, neurotoxic state, including promoting astrocyte reactivity, that leads to loss of oligodendrocytes and myelin as shown below.

The similarities between Long Covid brain and chemo-brain (cancer chemotherapy induced) have been duly noted by Monje and Iwasaki and laid out fully in their superb pathobiology review paper in Neuron. While actual infection of neurons is particularly rare, the inflammation process is the hallmark feature with several potential drivers (panels B through F below)

The Munich study has pointed to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein as a key inciting component of the inflammatory process. This concept was raised previously by others, such as in a post-mortem and brain stem cell organoid study by Crunfli and colleagues.

There have been several other very recent reports that extend the findings of neuro-inflammation and characterize the neurologic involvement in Long Covid. These include a functional MRI study that showed people with Long Covid, compared with healthy controls, exhibited an abnormal pathway of brain activation to perform cognitive tasks and another that demonstrated decreased regional brain oxygenation during cognitive tasks in symptomatic patients.

A common thread for the 2 new German studies is persistence of of neuro-inflammation, with the histologic or imaging findings present months after Covid illness. The persistence of the virus or its components, such as the spike protein, as a driver of the diverse, multi-organ involvement of Long Covid was recently reviewed and certainly this potential mechanism is reinforced by the new reports. The issue is what perpetuates the brain inflammatory process over time, with several pathways that have been proposed (above Figure). Moreover, the critical challenge that lies ahead is how to arrest this process and alleviate the neurologic symptoms that people with Long Covid are suffering. Calling for heightened public awareness of Long Covid this week, Wes Ely, an ICU physician at Vanderbilt University, wrote in the Boston Globe: “Numerous studies document the haunting brain impacts of Long Covid, from the loss of supportive cells in the brain called glial cells [glial cells of the brain are microglia, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes], to early death of our neurons leading to signs of early dementia in too many Long Covid patients, even young ones who had only mild infectious symptoms during their initial Covid infection.” The association of exposure to multiple viruses and subsequent neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, has been well established, as recently reviewed here and here.

The potentially reassuring finding of the Hamburg study was the lack of cognitive decline that was noted among the patients with mild to moderate Covid at 10 months. However, that differed from the UK Biobank and other reports that had longer follow-up, more patients with moderate Covid, and larger sample sizes. What is disconcerting to recall is the post-polio syndrome (known as PPS) that appears late—from 15 to 30 years after poliovirus infection—and what can be a disabling, progressive condition characterized by muscle atrophy, severe muscle weakness, falls, and chronic pain, and a leading theory for its basis is persistence of the virus or its components. The point here about SARS-CoV-2 is that we don’t have long-term follow up; we don’t know what will be the real impact on brain function. The persistence of neuro-inflammation at 1 year after even mild Covid should highlight this dangling concern and bolster our efforts to avoid infections and reinfections of this virus, along with definitive work to find safe and effective treatments.

Thank you for reading Ground Truths. If you found this informative, please share it.

Your free subscription denotes your support of this work. Should you decide to become a paid subscriber you should know that all proceeds go to support Scripps Research. That has already helped to bring on several of our summer high school and college interns.