I met Peter Attia in early 2020 when we did a podcast (The Drive episode #91, he’s now past #260). He’s an exceptionally bright physician with an outstanding medical training at Stanford, Johns Hopkins (surgery), and the National Cancer Institute (surgical oncology). His career path is atypical, since he left medicine for a stretch to work at McKinsey and Company in financial credit risk, a stint that he believes gave him a better understanding of risk in medicine.

Since Outlive was published at the end of March, I’ve had several patients come to clinic visits and ask me about various points in the book. So I knew it was time to give it a close read. In the introduction, he positions himself well: “This is how I see my role: I am not a laboratory scientist or a clinical researcher but more of a translator, helping you understand and apply these insights.” He provides extensive citations to support the vast majority of his assertions, with nearly 40 pages of single-spaced references. Overall, I think it’s quite worthwhile and well done, but I’ve got a few issues that I’ll discuss.

Major Themes and Strengths of the Book

Medicine 3.0

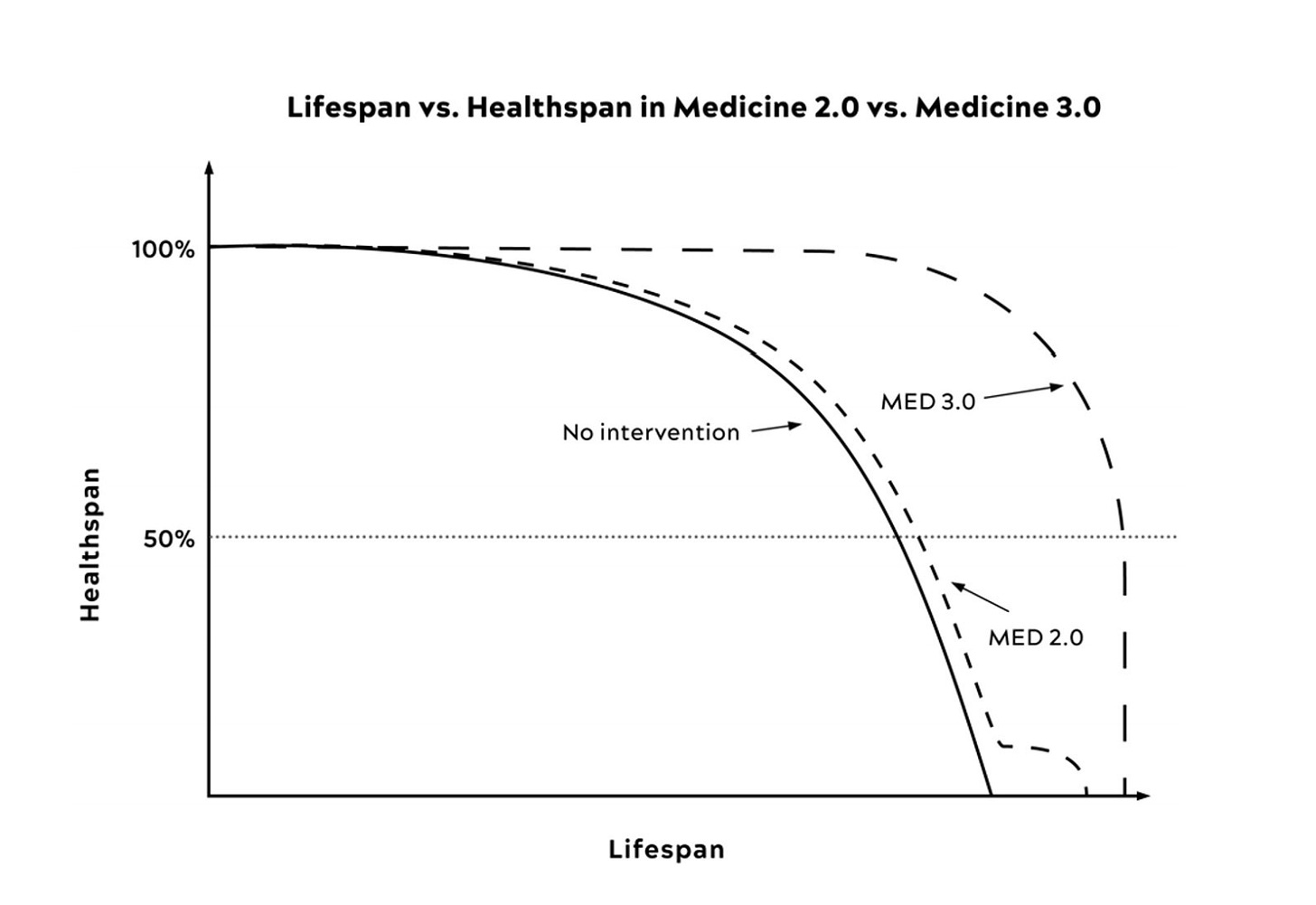

Rather than emphasizing longevity (“staving off death”), Peter’s “Medicine 3.0” is focused on maintaining healthspan with the major emphasis on prevention, recognizing each person as a unique individual. Throughout the book, he systematically reviews the ways this shift to the right of the theoretical curve below can be achieved. This means addressing and countering what he calls the “Four Horsemen”—heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s (and related neurodegenerative diseases) and metabolic dysfunction (insulin resistance, Type 2 diabetes). He does an exceptional job of weaving all the common threads together for these 4 chronic conditions, such as how metabolic dysfunction is a key underpinning across the board. Through details of his tactics of better exercise, nutrition, sleep, and emotional health, the Four Horsemen and our burden of chronic disease can be prevented, or, at the very least, forestalled. The overarching hypothesis is that a “compression of morbidity” might be attainable by preventing these conditions, reducing the time in decline, as shown by the sudden drop of the Medicine 3.0 curve below. It’s quite alluring, since we’d rather not live in a prolonged debilitated state. It’s hopeful, even likely, but it’s not proven.

Exercise

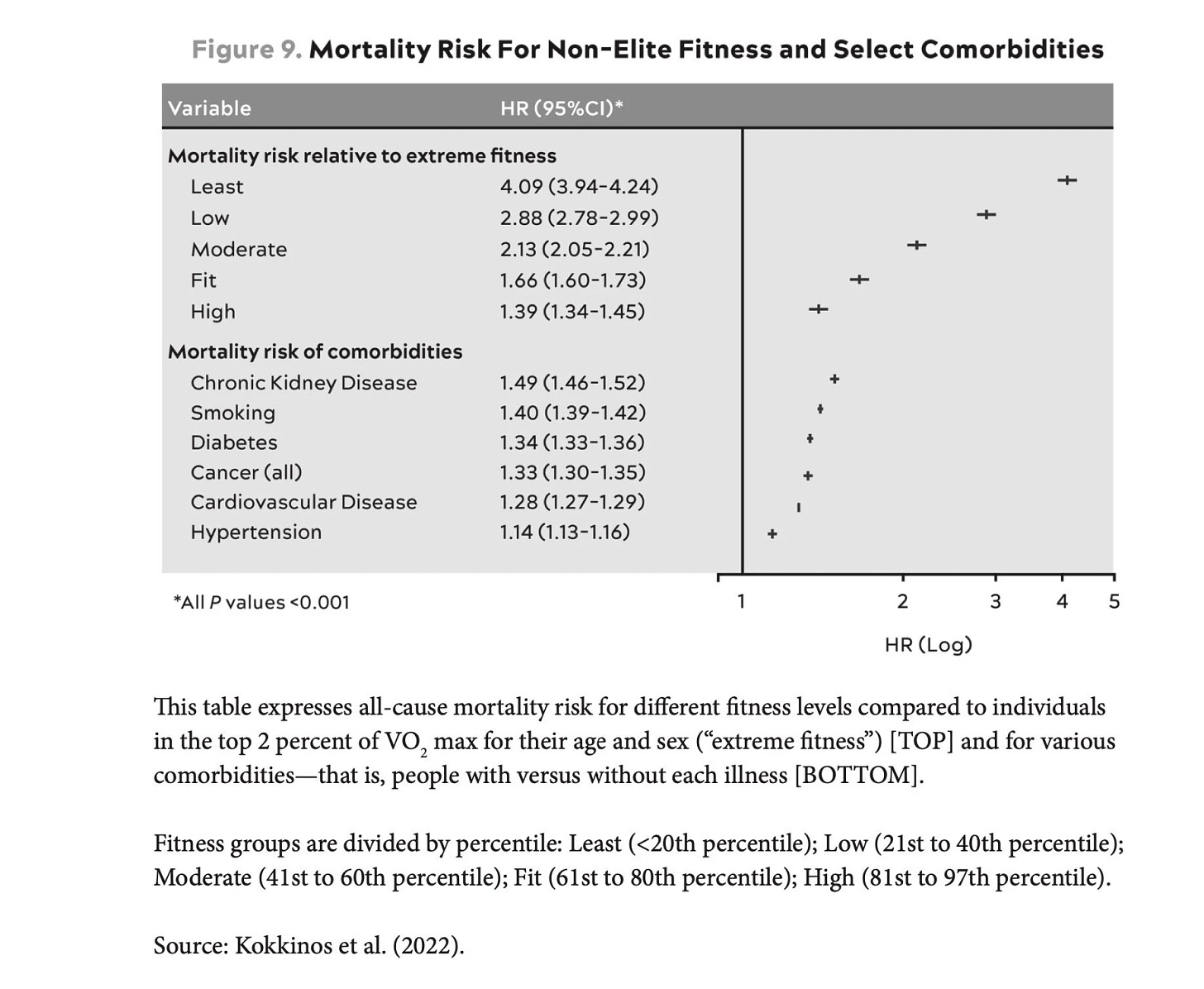

“I now consider exercise to be the most potent longevity “drug” of our arsenal.” Attia is really big on exercise, personally spending hours a day to be in top shape, and has dedicated several chapters and portions of the book to this and related matters of fitness, such as stability. One notable study he cites is from over 750,000 U.S. veterans ages 30 to 95. The least fit 20% group had 4-fold higher risk of dying than a person in the top 2% of their age and sex category (Figure below, JACC, 2022). He reiterates the paper’s conclusion: “Being unfit carried a greater risk than any of the cardiac risk factors examined.”

Nutrition

While most physicians do not emphasize (that’s putting it politely) its importance, Attia is deeply into this and conveys much useful information, especially in Chapters 14 and 15. He goes through his recommendation for protein intake per day—1 gm per pound—which is nearly 3-fold the minimal recommendation, no less obtaining 9 of the 20 amino acids from our diet since we can’t synthesize them. He gets into depth for each of the energy substrates (warning against alcohol, putting carbs in context, along with good and bad fats). There is no push for supplements, which is refreshing to see with little to no data to support their use. Whereas he used to advocate the keto diet as beneficial, he’s revised his perspective, and is much more balanced about the right, individualized nutrition plan, whether it is caloric restriction, dietary restriction, time-restricted eating, or whatever works to achieve the objective of being metabolically healthy.

Insulin and Metabolic Dysfunction

Attia really shines with his knowledge in this area, and it’s the best presentation of the data and explainers that I’ve seen. He makes a solid case for insulin resistance to be recognized as a critical condition, since it’s the precursor to not just diabetes, but also liver disease (NASH and NAFLD), and the other 3 Horsemen. We’ve placed too much emphasis on obesity per se, without zooming in on metabolic dysfunction which can occur in people who are lean (approximately 33 million of the 100 million Americans with metabolic dysfunction are non-obese). 90% of American adults have at least 1 of 5 factors of the metabolic syndrome (hypertension, high triglycerides, low HDL, high fasting glucose, and central adiposity).

Other Good Stuff

Some other things I particularly liked are his great use of metaphors for explainers of complex topics, for example: “atherosclerosis as kind of like the scene of a crime—breaking and entering, more or less. Let’s say we have a street, which represents the blood vessel, and the street is lined with houses, representing the arterial wall. The fence in front of each house is analogous to something called the endothelium, a delicate but critical layer of tissue that lines all our arteries and veins…”

That’s in the heart disease chapter, which he covers well, making the case for ApoB and Lp(a) measurements to supplement LDL and HDL cholesterol for risk assessment. To get a very good handle on a person’s genetic risk beyond blood tests, I use the heart disease polygenic risk score with my patients. Our team at Scripps developed a free app for this purpose. I agree with his perspective on the value of knowing one’s ApoE isoform. His summary statement about women and heart disease can’t be highlighted enough: “American women are up to 10 times more likely to die from atherosclerotic disease than from breast cancer (not a typo: one in 3 vs 1 in 30).”

I love the way he rips on Hippocrates “Do No Harm,” covers very difficult areas like Mendelian randomization, and reviews the Bradford Hill criteria for strength evidence of epidemiology. His personal and patient’s insights about using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) are valuable (full disclosure: I am on the BoD of Dexcom, so I stay away from advocating CGM).

The last chapter (“Work in Progress”) is especially poignant, in which Peter reveals his abuse as a child, his personal mental health difficulties and how he’s dealing with it. When I met Peter to do the podcast his marriage was in rocky shape, so it is terrific to see how all is good now with his wife and family.

Some Concerns

There are a few points where it seems Peter gets off track of a supportive body of evidence, or gets ahead of his skis. For example, he takes rapamycin (page 88) and apparently advocates its use in his patients, because of the data of consistent benefit for improving longevity across animal species. But, as he also points out, it induces immune system suppression (it’s a drug to prevent organ transplant rejection) so it may not be safe. He apparently suggests his patients get total body MRI imaging (page 172) to spot cancer early. There aren’t any data that I know of, except anecdotal data from companies like Human Longevity Inc, which incorporates this in their expensive checkup package. The concern I have here is engendering “incidentalomas” (a word my friend Issac Kohane coined)—that is finding something that leads down a rabbit hole that has to be chased down, like a nodule in the lung or liver that requires a biopsy, which carries risks, no less considerable anxiety and expense. In short, total body MRI could do more harm than good and we need prospective studies to meaningfully assess this approach. Multi-cancer early detection blood tests may ultimately prove to be a better tool, spotting cancer well before it is large enough to be a mass on an MRI, but that’s also not adequately validated, as I’ve recently summarized.

The bigger picture issue is that the full package that Attia presents, what he and his colleagues provide in their clinic, is not affordable except for the most affluent individuals. But that doesn’t detract from his book that is highly informative, with many ways to take a more aggressive position to promote one’s health. It’s inspirational. We know as physicians how hard it is to get people to take charge of their health and develop comprehensive plans to focus on exercise, nutrition, sleep, and mental health—by reviewing the science behind, in depth, and in a way people can understand it, this book helps people do that.

I’ve invited Peter to turn the table and do a Ground Truths podcast to discuss the book further and address the points I’ve raised here—I’m hopeful he’ll find the time to do it in the weeks ahead.

Finally, let me say I’m very appreciative to Peter for the multiple years and arduous work he put into writing Outlive. It’s an important resource for people who want to take more initiative to stay healthy, and it is deserving of its major success.

Thanks for reading Ground Truths!