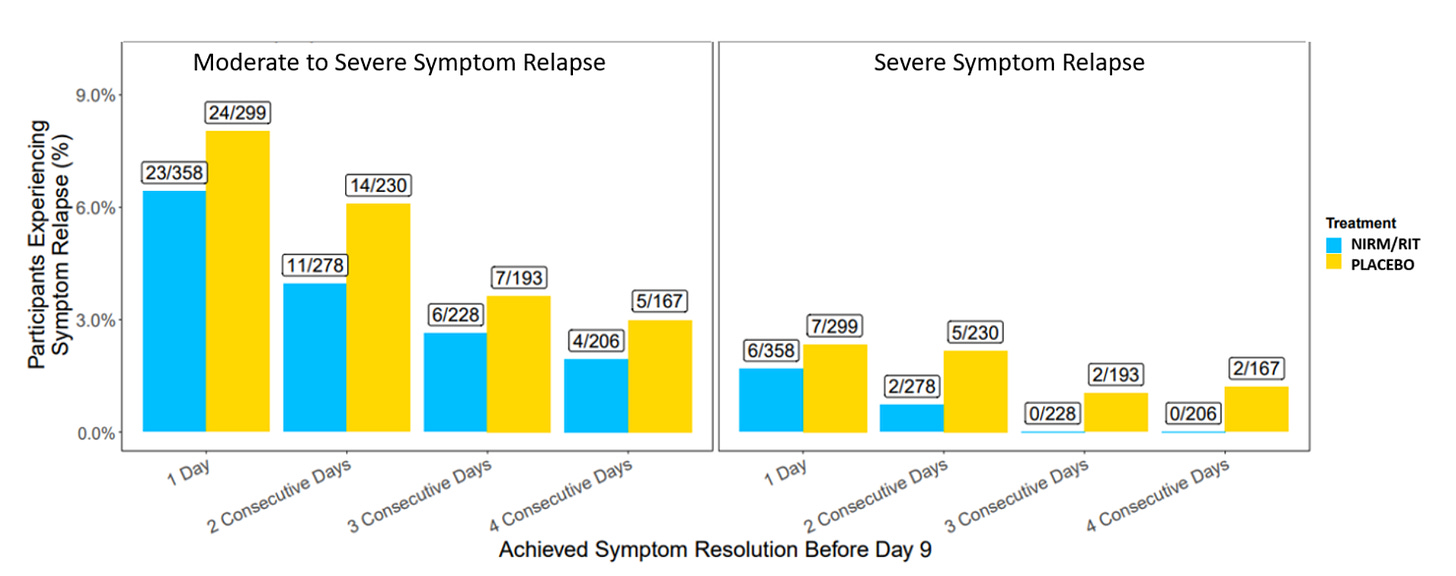

Concerns that Paxlovid rebound is extremely common cropped up in recent months with millions of prescriptions of the 5-day treatment pack in the US. All of us know of people who experienced rebound symptoms and a positive rapid antigen test after completing Paxlovid treatment, which led to calls for consideration for a longer course of treatment. In the main randomized clinical trial (EPIC) of Paxlovid in high-risk patients, the frequency of viral load rebound was very low: 2.3% in the Paxlovid group (990 patients) and 1.7% in the placebo group (980 patients). The symptom data are shown below, which lacked any excess in the treatment group. These findings certainly didn’t correlate to the real-world perception. Perhaps the fact that the trial was performed during the Delta wave and with unvaccinated participants could account for results that were so different during the Omicron sublineage waves (BA.2, BA.2.12.1, BA.5) in the United States, and that many of the people reporting Paxlovid rebound had been vaccinated.

Then we saw President Biden, the CDC Director, Rochelle Walensky, and Anthony Fauci all experience rebound, which reinforced the sense that Paxlovid rebound was quite problematic and common, perhaps even to be expected in the majority of treated patients. Indeed, many physicians and patients were (and are) unwilling to prescribe or take Paxlovid, thinking it was better to confront the infection without interfering with one’s immune response or engendering risk of a protracted illness.

But we were missing a prospective, systematic assessment—with controls—to get a handle on what was really happening. My colleagues, Jay Pandit at Scripps Research Translational Institute and Michael Mina at eMed, designed such a decentralized trial with rapid enrollment of 247 participants between August and November 2022. Importantly, the study was independent from Pfizer without any funding or support in any way. When we discussed the trial, we expected the rate of Paxlovid rebound (excess compared with controls) might be 30% or higher.

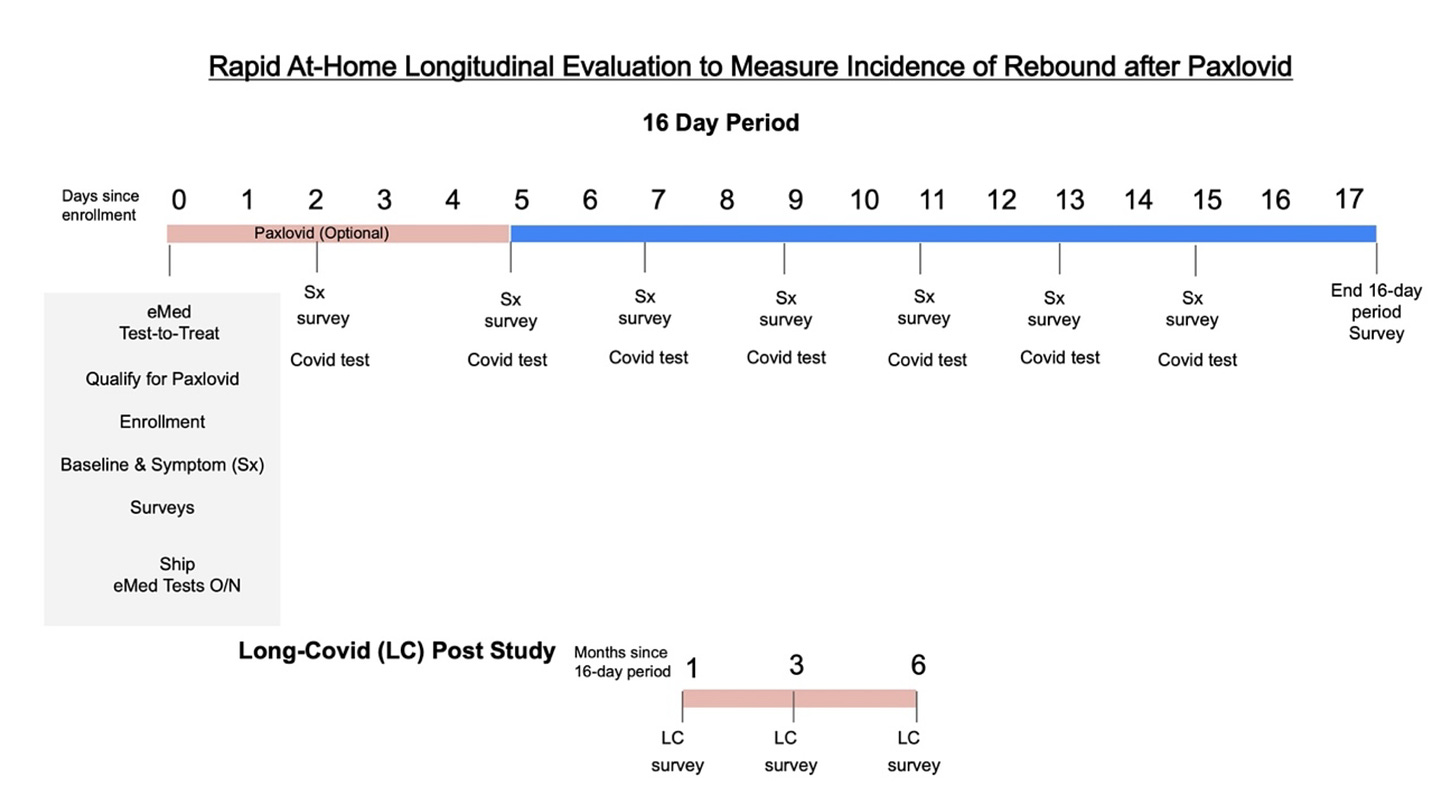

The protocol is shown below with every other day rapid antigen testing out to day 15, symptom survey out to day 17, and 6-month follow up. 170 people completed the protocol: 127 in the Paxlovid group and 43 in the control group. 95% of the patients were vaccinated with at least 1 dose.

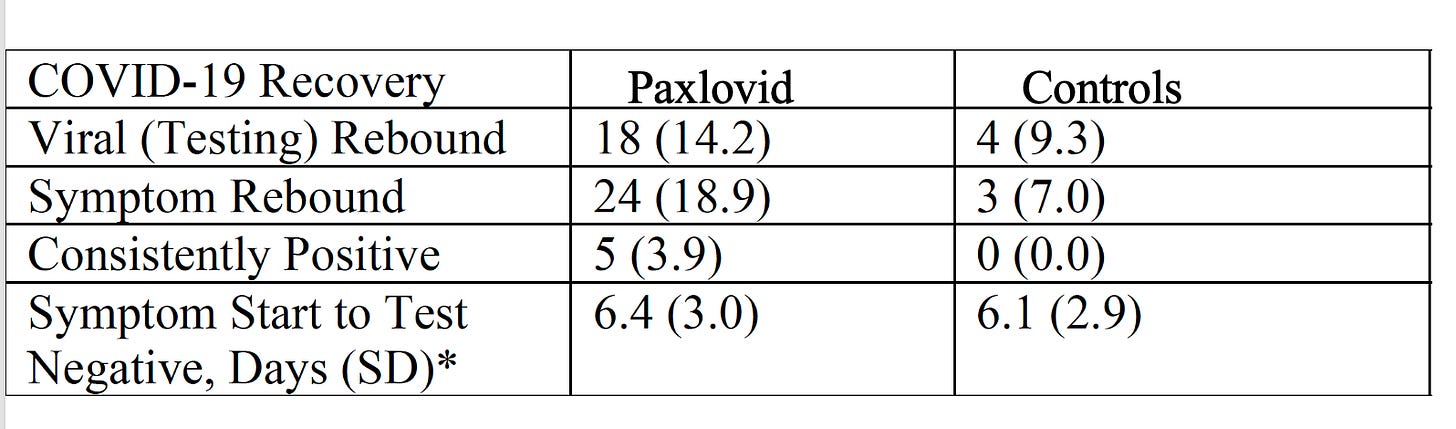

The results are summarized below. By rapid antigen testing, viral rebound occurred in 14% of the Paxlovid group and the excess compared with controls was 5%. With respect to symptoms, it was nearly 18% compared with 7%, an excess of 12% for Paxlovid versus controls. These rates are considerably higher than the EPIC trial, reviewed above, but far less (especially flanked by controls) than the perception in the medical community and the public.

Of course, more studies need to be done to replicate and extend these findings, along with fully understanding the mechanism of rebound (for both Paxlovid and non-treated). But I think there are 3 important takeaways from these data:

We can’t rely on perceptions based on anecdotes and social media. There is a bias of ascertainment and reporting, since the people who did well with Paxlovid, without rebound, are likely to be quiet, no less the people who did not take Paxlovid but later developed positive tests, with or without symptoms. The only way to know is to conduct a prospective, systematic clinical trial, with controls, which our group did, to shed light on the frequency of this Paxlovid problem.

Paxlovid rebound highlights the importance of real world effectiveness studies—that randomized, placebo-controlled trials (RCT) are not the end all body of evidence. Here the RCT led us to believe that rebound was extremely rare, but it was clearly higher in the clinic. While the mechanism for rebound is not fully resolved, the virus strain during the RCT was quite different than the subsequent Omicron lineages. And the patients in the RCT were unvaccinated, so extrapolation to a population with the majority having had some vaccine-induced immune was strained. Further, the RCT had less than 2,000 patients enrolled whereas over 10 million people have been treated now, and the demographics of the RCT sample may not have been representative of the population treated for many other features besides vaccination status.

The excess in rebound with Paxlovid versus controls is low, 5-12% for viral testing rebound and symptomatic rebound, respectively. That is considerably less than our expectations and some estimates that have been shared that were well over 50%. This should be reassuring to prescribers (which include pharmacists) and patients, that the chances of rebound are low. The empiric need to take longer duration of Paxlovid (i.e. 7-10 days) is reduced from these findings, but certainly that strategy should be further explored, especially if there is a way to know a priori which individuals would be at risk for rebound and might benefit from a longer course.

That brings me to my recent post about Paxlovid and reduction of Long Covid, an unexpected bonus, and a reason to consider treating with Paxlovid, which was associated with a 26% reduction in the Veterans Affairs report.

I hope the new Scripps Research study will help alleviate some concerns about excessive rebound and get the right balance for decisions for treating with Paxlovid.

Thanks for reading, sharing the post, and your subscription to the Ground Truths newsletter.