Polygenic Risk Scores: Ready for Prime Time?

A new multi-ancestry report on 10 conditions moves us forward

“The potential impact of polygenic risk score (PRS)-based risk assessment in clinical practice is substantial”—eMERGE investigators

Today in Nature Medicine, Niall Lennon and 80 co-authors published an important paper, advancing the clinical case to use polygenic risk scores for determining high-risk across 10 common conditions.

Established in 2007, the eMERGE (Electronic Medical Records and Genomics) multicenter consortium has, in recent years, been working on improving, validation, and clinical implementation of polygenic risk scores. That includes expanding data inputs to achieve diverse ancestry and ethnicity, assessing performance, developing threshold for high-risk, selecting which PRS conditions have high performance and actionability for high-risk individuals, and creating reports for individuals so they can readily interpret their findings.

Some Background

Recall that a PRS is a large collection of common genomic variants, often hundreds, that are associated with a given condition through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), with rigorous thresholds for statistical significance. These variants do not necessarily represent underpinnings of the condition of interest, but may tag genes or regions of the genome that are functionally important—and in some cases actually have a cause and effect relationship. Importantly, each validated PRS adds independent information to clinical factors for categorizing a person’s risk. That’s why it’s worthwhile to know, for example, if an individual has little or no risk from clinical criteria, whether there is high-risk at the genomic level. You might consider that otherwise hidden information. Case in point: I have no family history or risk factors for coronary artery disease, but have a very high CAD risk score in the top 1%.

We’re talking about actionability. Like taking a statin to prevent heart disease (fully validated by PRS for coronary artery disease), or need to undergo a screening test for cancer. Not for a condition for which there’s no preventive strategy known.

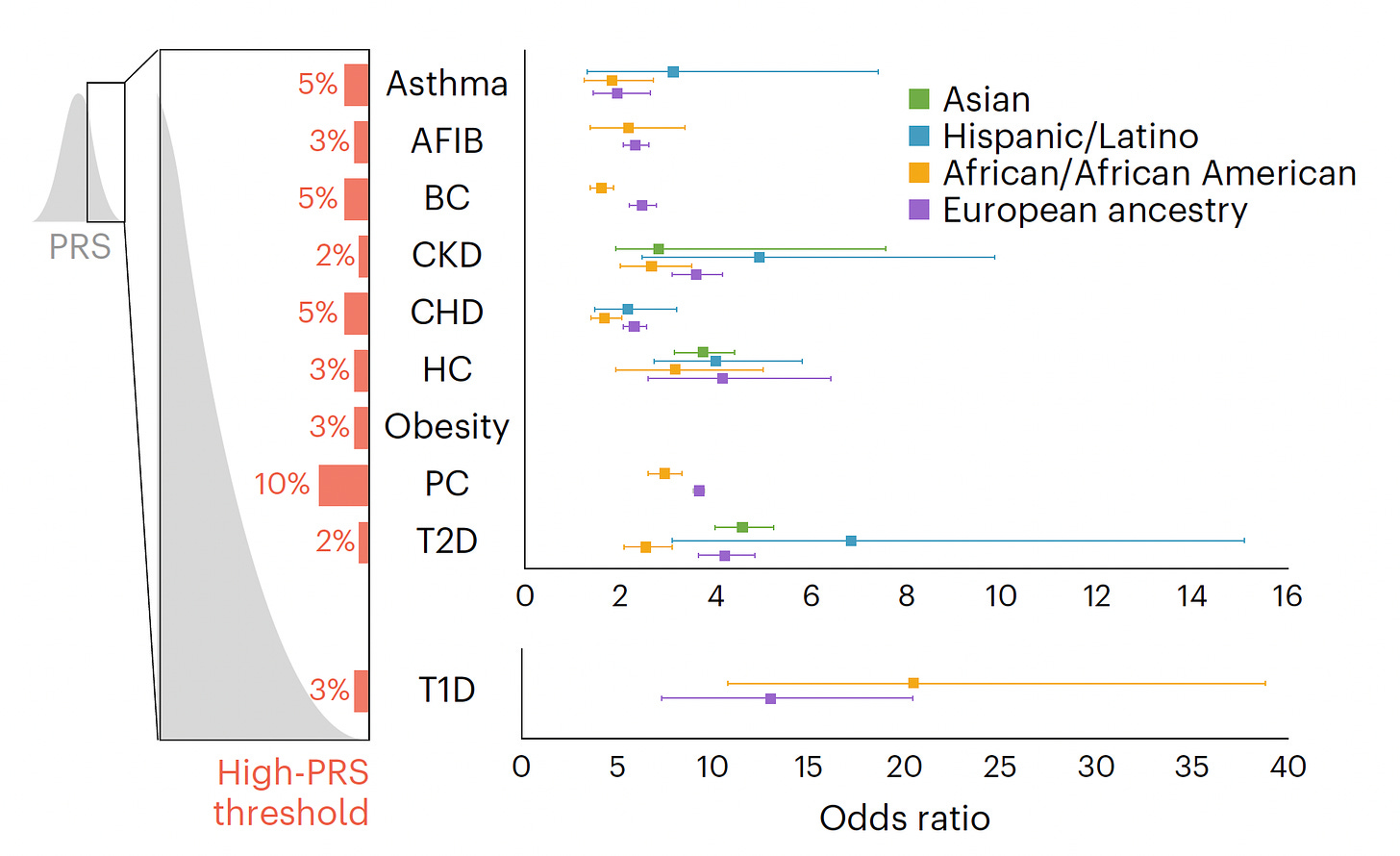

The eMERGE Report

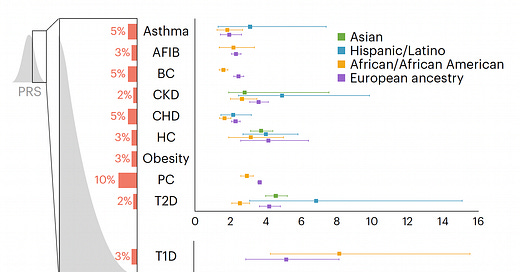

Back to the study at hand. Starting with a PRS for 23 conditions, eMERGE winnowed down to just 10 that met all the selection criteria, and divided people into 4 populations as shown in the Figure below. For each condition the threshold for categorization as high-risk is shown (varying from 2 to 10%) and the odds ratio for each of the 4 populations provided. As you can see, the odds ratios were high, ranging from approximately 2 to 7-fold risk across the 10 diseases, with some inter-ancestry variability.

The PRS process started with a 1.8 million SNP array (from Illumina) imputed with the 1,000 genomes data, adjusted by principal component analysis. Accuracy of the PRS (correlation with whole genome sequencing) across all 10 conditions was very high, ranging from a low of 93% for breast cancer to 99.5% for Type 1 diabetes and obesity. Precision, as measured by repeatability, was 100% for all 10 conditions.

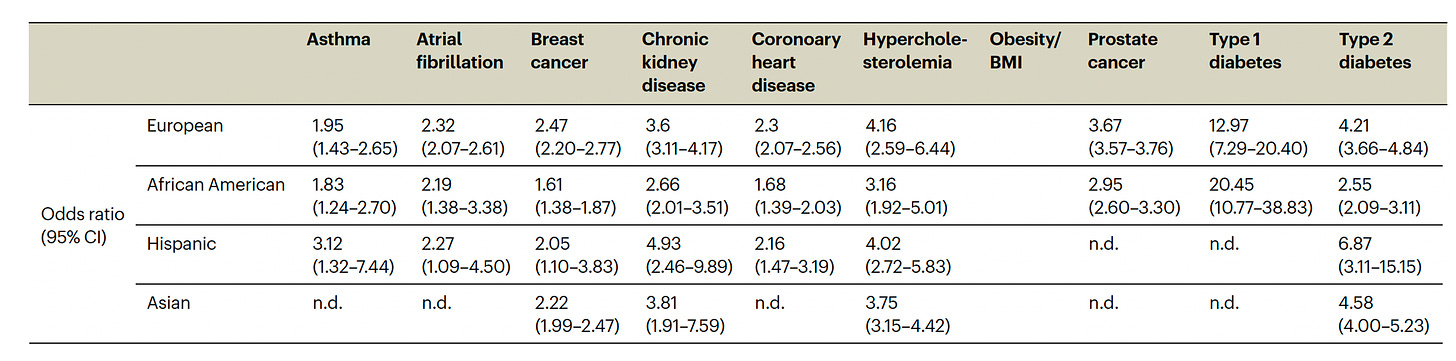

The actual odds ratio data with 95% confidence intervals, corresponding to the graph above, is seen in the Table below. n.d. is not determined due to inadequate number of individuals of a given population assessed.

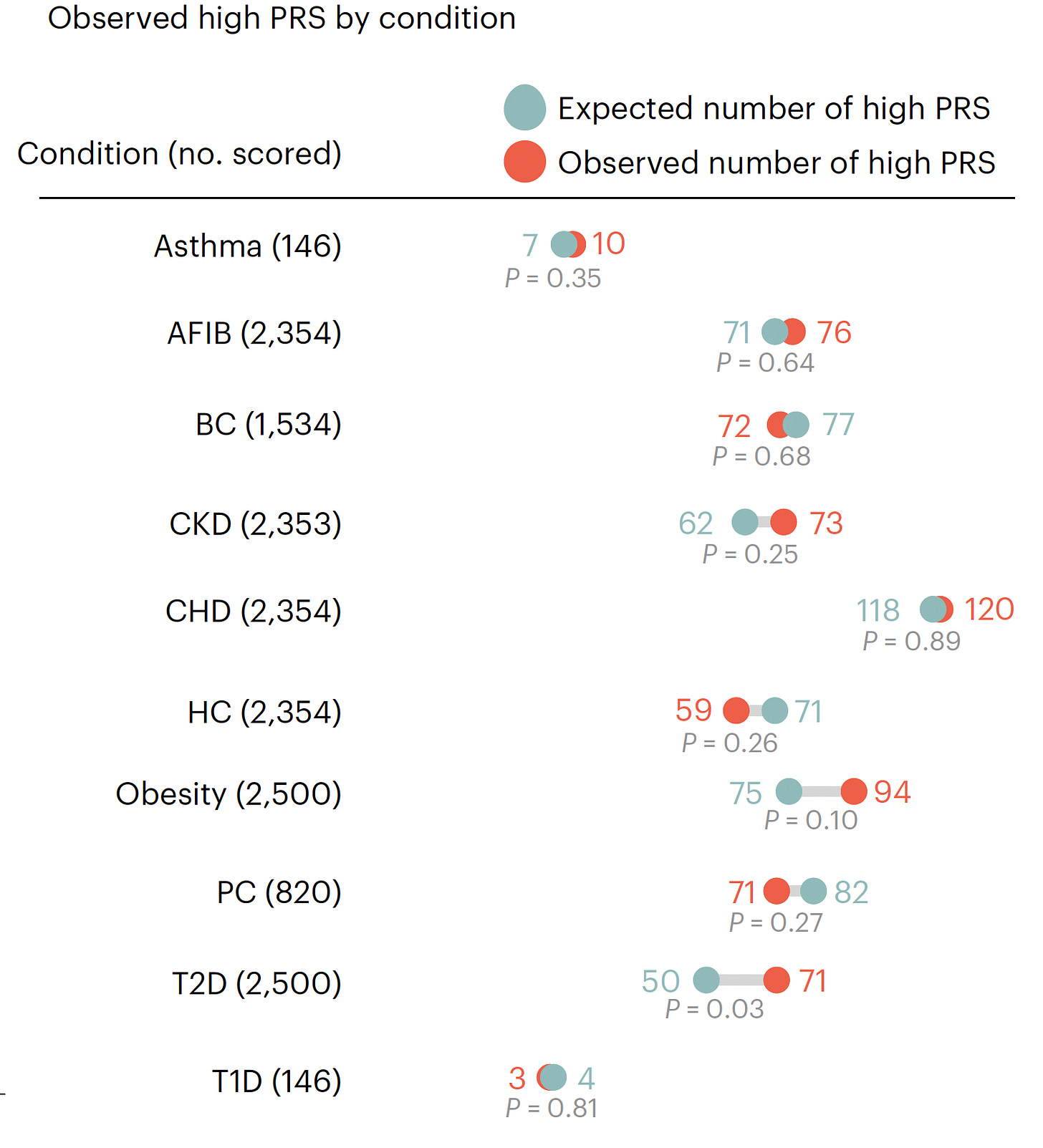

As assessed in the first 2,500 people prospectively, 20.6% had at least 1 high-risk PRS, 2.6% had 2 PRSs that were high-risk, and only 2 individuals had 3 high-risk PRSs. The number found to have a high-risk PRS (both expected and observed, no significant differences except for T2D) for each of the 10 conditions is shown below. High-risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) had the highest yield

eMERGE plans to assess another 22,500 people prospectively, but it’s quite likely that adding more participants will not result in a material change of their findings.

Concerns about inequity? “PRS-based risk assessment in diverse populations has the potential tor educe health disparities by ensuring that clinical use of PRSs accurately reflects disease risk in diverse populations.”

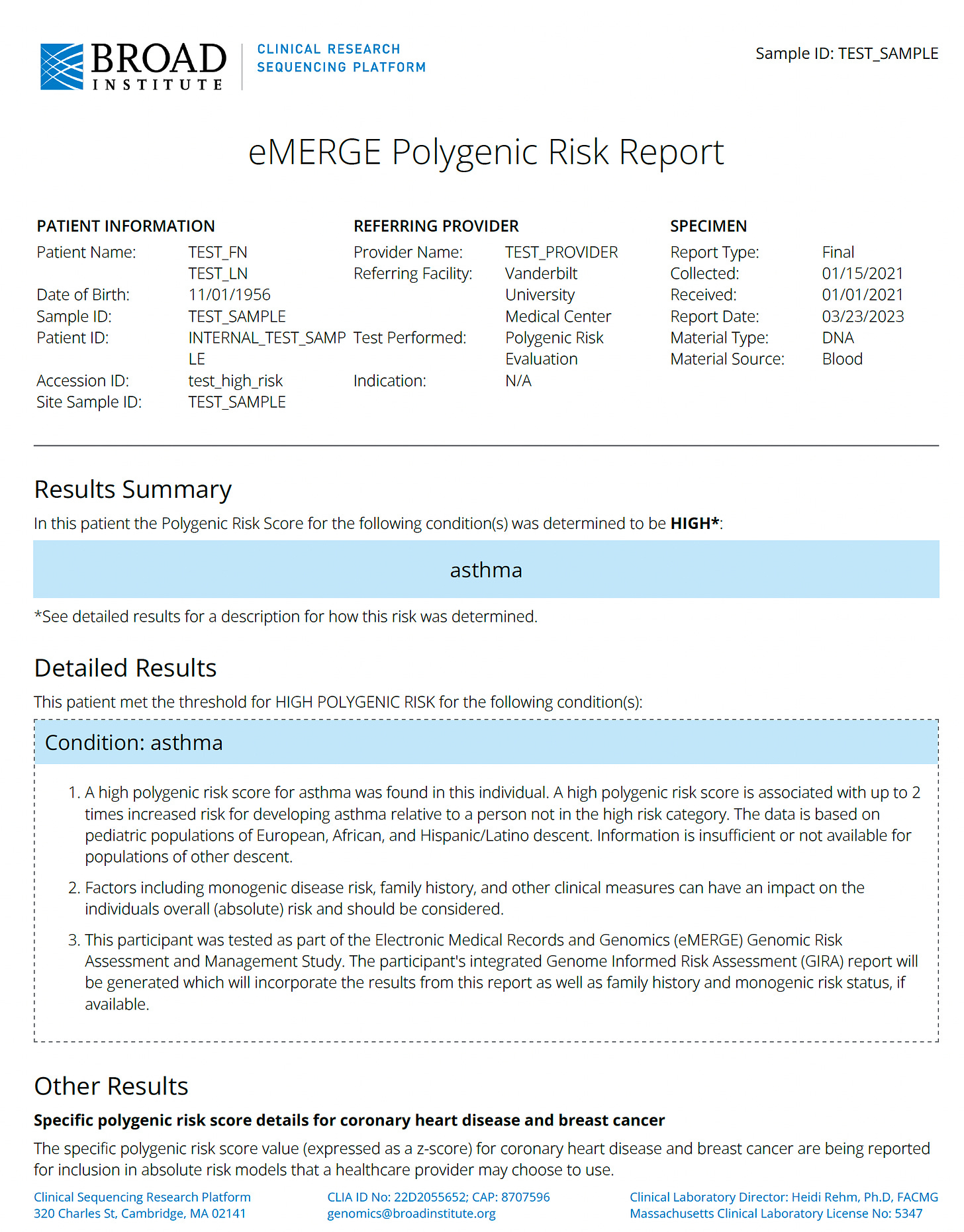

Here is a sample of the clinical report they developed

Their bottom line: “In conclusion, the eMERGE Network’s work in PRS development represents an important step forward in the implementation ofPRS-based risk assessment (in combination with other risk estimates from monogenic testing and family history) in clinical practice.”

Ready to Implement?

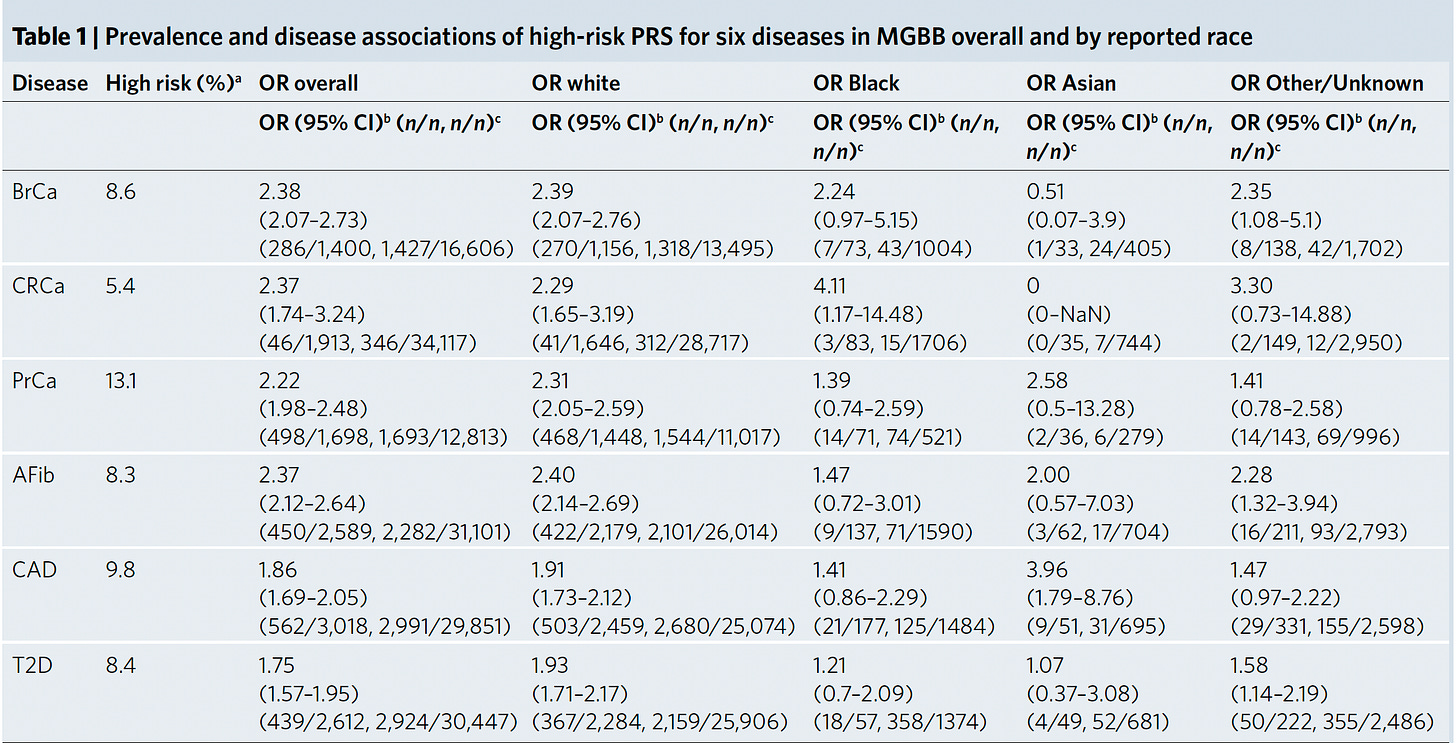

Last year, the Mass General Brigham health system started a plan for implementing PRS for their patient population for 6 conditions, all but 1 (colon cancer) overlapping with the new report. The thresholds for high-risk were somewhat different and their results broken down by ancestry into three groups below.

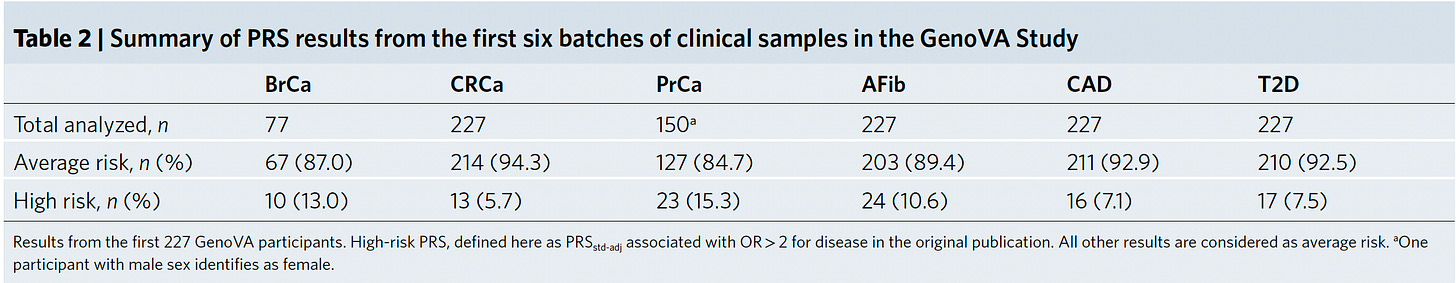

And here, prospectively assessed in 227 participants

Their conclusion was very similar to the current report: “data from increasingly larger and more diverse populations, coupled with computational advances, are propelling PRS into consideration for clinical implementation.”

The Answer is Yes, But…

Using PRS to know if a person has high polygenetic risk for an important condition like heart disease or cancer is long overdue. The problem has been lack of adequate multi-ancestry data and validation. We’re getting over that barrier now.

The paternalistic genetics community doesn’t believe people can understand probabilistic thinking, that they will get a PRS deemed “high-risk” and automatically conclude they are destined to have that condition. I disagree with that bent, and my experience is that, with proper explanation, this should not be considered a reason to withhold their data. I emphasize their data.

Next is the problem that a PRS doesn’t say when. There is no age cutoff, so the risk could be at anytime along one’s lifespan. Yes, that adds to the fuzziness since age of onset data are lacking. It’s a shortcoming, but knowing one’s genetic risk when very high is still worthwhile, irrespective of when it may manifest.

There is also the need to integrate clinical factors with genomic data, which doesn’t get done by providing a PRS result by itself. That where’s multimodal A.I. can kick in, and for now clinicians can help do that with a patient’s data.

The next problem is how to get a PRS?

There are several companies that market PRSs to consumers

23andMe (initial fee and $5 per month subscription to get PRSs), Myriad Genetics, Allelica, and Ambry Genetics.

There are also companies marketing PRSs through health systems

Open DNA, Genotype, Genomics PLC, and Allelica.

But these companies are not using multi-ancestry, state-of-the-science PRS adjusted risk scores, like what has been reported today. Their data are not transparent for thresholds and validation. Following the post, 23anMe pointed me to a white paper on their methodology and that their threshold for a high PRS (“increase likelihood”) is an odds ratio > 1.5.

Summary

Actionable polygenic risk scores should be part of medical practice, be made widely to the public, and be used widely by clinicians to help promote prevention of diseases in their patients. The eMERGE consortium report and dataset could be the basis for that long overdue, unmet need. Their careful and rigorous work to move this forward should be considered seminal, as it could help to finally bring two decades of GWAS data into the public domain and for the medical community to use on a daily basis. Let’s hope we’re at a turning point to make PRS the real deal (finally).

Thanks for reading Ground Truths.

Please share if you found this post helpful.

All content on Ground Truths—newsletter analyses and podcasts—is free.

Voluntary paid subscriptions all go to support Scripps Research.