100 years ago, the first Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital was published in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, the precursor to the New England Journal of Medicine, which has been publishing what are known as clinicopathologic conferences (CPCs) since 1924 on a biweekly basis.

In this week’s NEJM CPC, a case of a 19-year-old woman presented with respiratory failure that started with difficulty breathing during exertion and cough during a vacation cruise with her family 2 weeks previously, and “shortly after a dental procedure.”

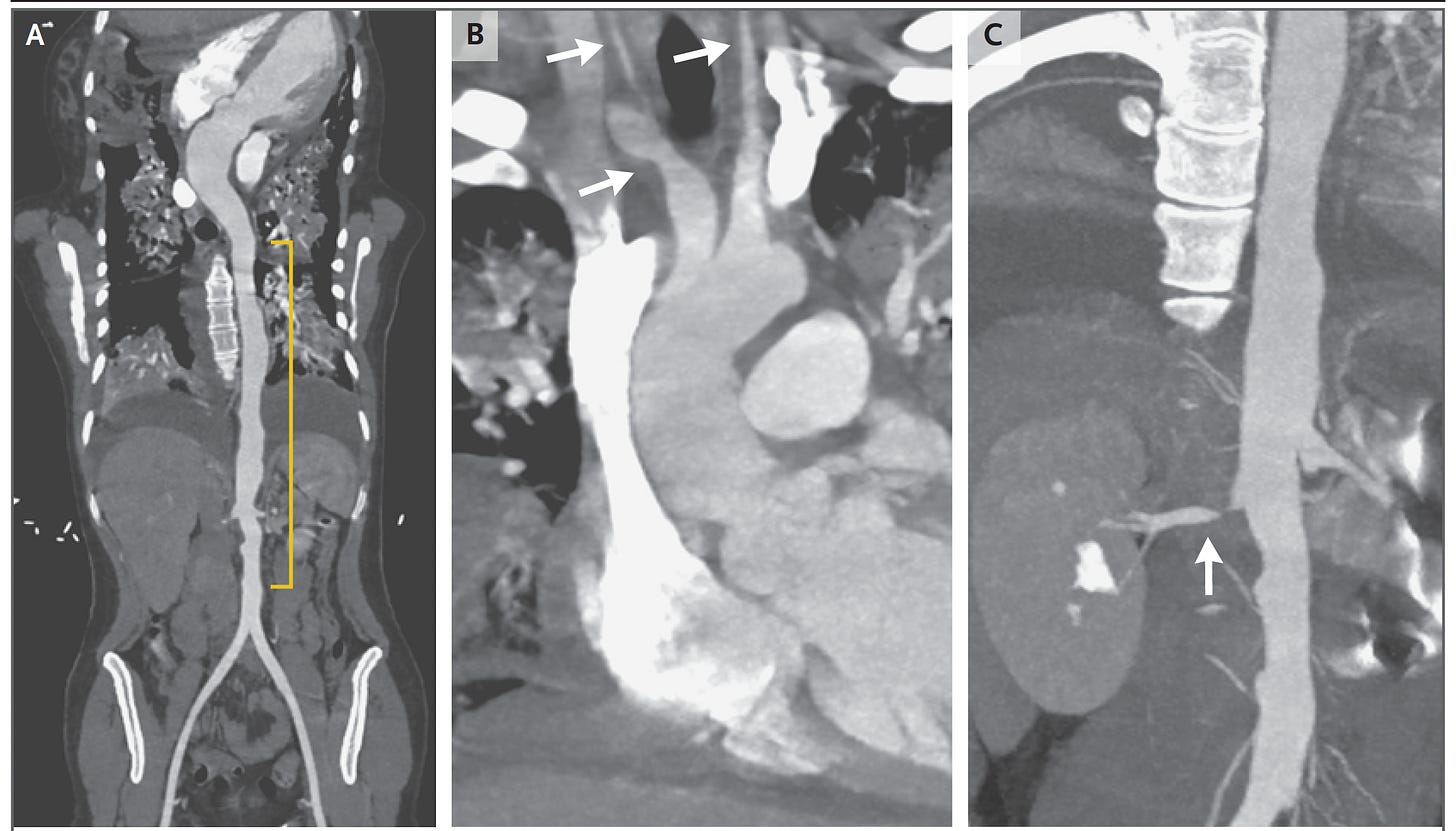

There were no shortage of red herrings but it turned out that she had Takayasu’s arteritis, although not confirmed by a biopsy of the aorta at the time of surgery, but shown by the CT angiogram below with a highly irregular contour of the aorta and focal narrowings to some of the major branch arteries. The differential diagnosis included many conditions such as infectious aortitis, giant cell arteritis, and systemic IgG-4 autoimmune disease. Takayasu’s arteritis is extremely difficult to diagnose because its presentation is so highly variable and it’s quite rare. This patient did not present with the usual symptoms of weight loss, joint and muscle pain, and signs of specific arterial blood supply deficits. Nevertheless, the correct diagnosis was made by a rheumatology expert, Dr. Cory Perugino.

The CPC is a longstanding tradition that continues in many medical centers throughout the world, first introduced in the United States in 1898, undoubtedly influenced by Giovanni Battista Morgagni who published a book of 700 cases with anatomy-clinical correlations in 1761. As they evolved over the years, CPCs were extremely challenging patient cases to stump the medical expert. After presentation of the relevant data, the clinician expert would be asked to provide a differential diagnosis and presumptive final diagnosis, and the actual, definitive diagnosis was established via lab tests, scans, pathology, or autopsy. The CPC educational value is clearcut, but so was there entertainment to see if the noted expert might miss the diagnosis. Of course, there was the expectation that the master clinician—the doctor’s doctor— would always get it right. I vividly remember trying to stump UCSF Professor Larry Tierney during my internal medicine residency training, but it was rare that he didn’t have the right diagnosis in his differential.

That rarity of expert wrong diagnosis differs substantially from real world medicine. After a classic Science 1974 paper about uncertainty, one of its authors, Danny Kahneman, wrote about a study that compared the doctor’s diagnosis before death to the autopsy findings. “Clinicians who were completely certain of the diagnosis antemortem were wrong 40 percent of the time.”

Also worthy of highlighting: 50% of doctor performance is below average.

The CPC benchmark and a new study using GPT-4

The New England Journal CPCs have been the benchmark for evaluating medical diagnostic reasoning, as used in the 1959 paper in Science Magazine, emphasizing the role of mathematical techniques and associated use of computers noting: “This method in no way implies that a computer can take over the physician’s duties.”

In 1982, the INTERNIST-1, a computer-assist diagnostic tool, was compared with clinicians for 19 NEJM CPCs and deemed “not sufficiently reliable for clinical applications.” More recently, CPCs have also been the benchmarks for computer-aid diagnostic tools, also known as differential diagnosis (DDx) generators, for many years.

In this week’s JAMA, Kanjee, Crowe, and Rodman published a comparison of 70 NEJM CPCs for the medical expert diagnosis compared with GPT-4.

The prompt (with thanks to Adam Rodman for forwarding it to me) was the following:

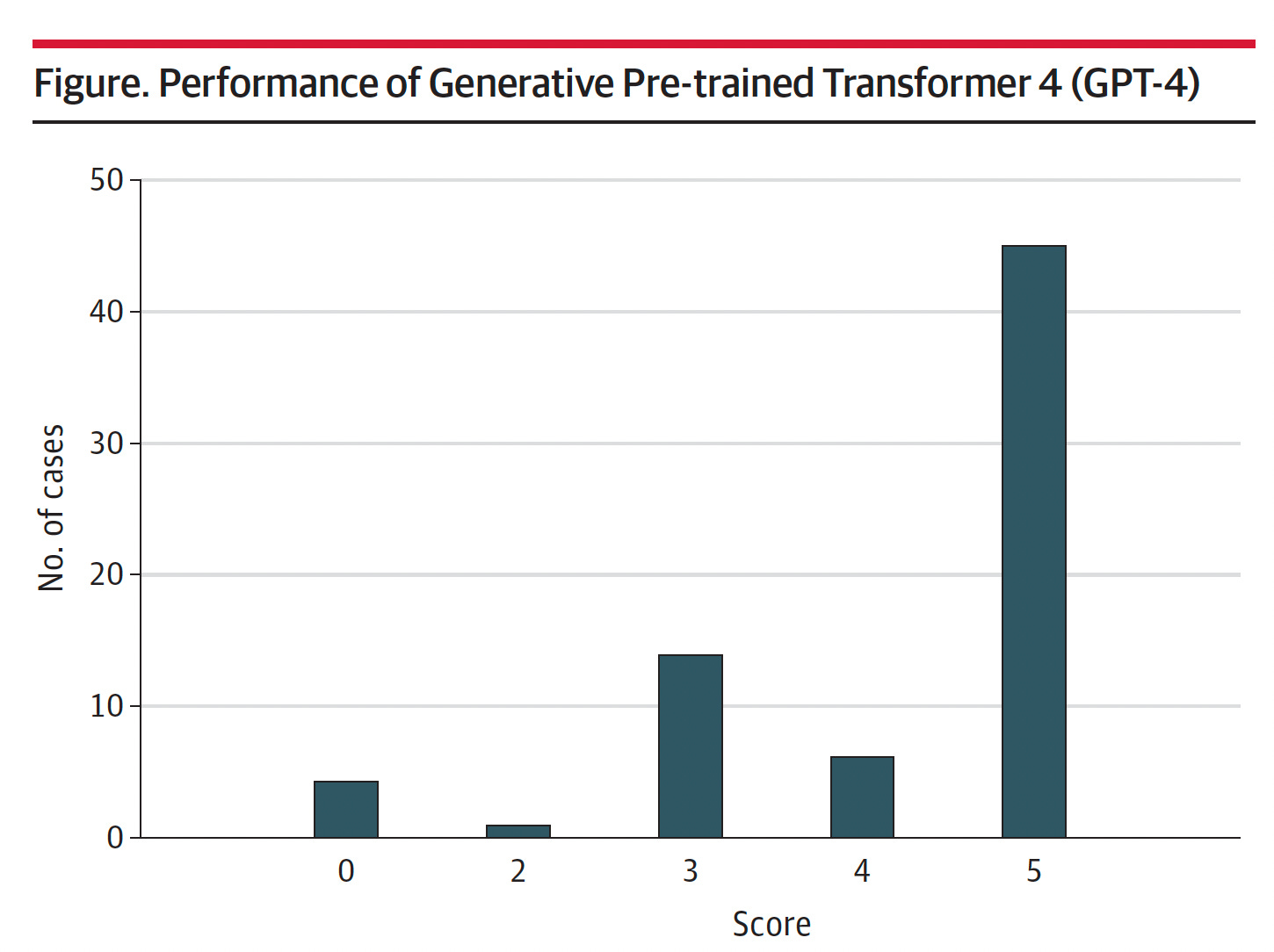

Using a 5-point rating system, a score of 5 corresponded to the actual diagnosis listed in the differential, and a score of 0 means it was missed—that no diagnosis in the differential was close to the actual diagnosis. The cases were independently scored by the first two authors of the paper. The mean score was 4.2. For 45 of the 70 (64%) cases, the correct diagnosis was included in the differential and it was the top diagnosis in 27 of 70 (39%).

To date, the best DDx generator results that have been published are derived from Isabel Health’s tool. In the most recent report with Isabel DDx data, two doctors (not medical experts) got 14 of 50 (28%) of the NEJM CPC final diagnoses. As the current report asserted, “GPT-4 provided a numerically superior mean differential quality score compared with an earlier version of one of these differential diagnosis generators (4.2 vs 3.8).”

The Future Role of LLMs in Diagnosis

Here’s what Adam Rodman, the senior author of the paper, wrote about the findings:

I agree with Dr. Rodman. We need to prospectively assess GPT-4 for its role in facilitating diagnoses. This is a major issue in medicine today: at least 12 million Americans, as out-patients, are misdiagnosed each year. There is real promise for GPT-4 and other large language models (LLMs) to help the accuracy of diagnoses for real world patients, not the esoteric, rare, ultra-challenging NEJM CPC cases. But that has to be proven, and certainly the concern about LLM confabulations is key, potentially leading a physician and patient down a rabbit-hole, towards a major wrong diagnosis and an extensive workup without basis, no less the possibility of an erroneous treatment.

There’s been much buzz about ChatGPT, GPT 3.5, Med-PaLM, and GPT-4 surpassing the 60% pass threshold for the United States Medical Licensing exam (USMLE) (to reach ~86%). These are fairly contrived comparisons using a subset of representative questions and only those with text, not with visual media. It makes for nice bragging right for LLMs, but we aren’t going to be licensing any of them to practice medicine! That’s far less relevant than use of these AI tools for promoting accurate diagnoses.

I’m excited about this particular use case of LLMs in the future, especially as they undergo supervised fine tuning for medical knowledge. It clearly needs dedicated, prospective validation work, but ultimately may become a significant support tool for clinicians and patients. If GPT-4 can perform well with arcane NEJM cases, imagine what might be in store for the common, real world diagnostic dilemmas.

Thanks for reading Ground Truths. If you found this post of interest, please share