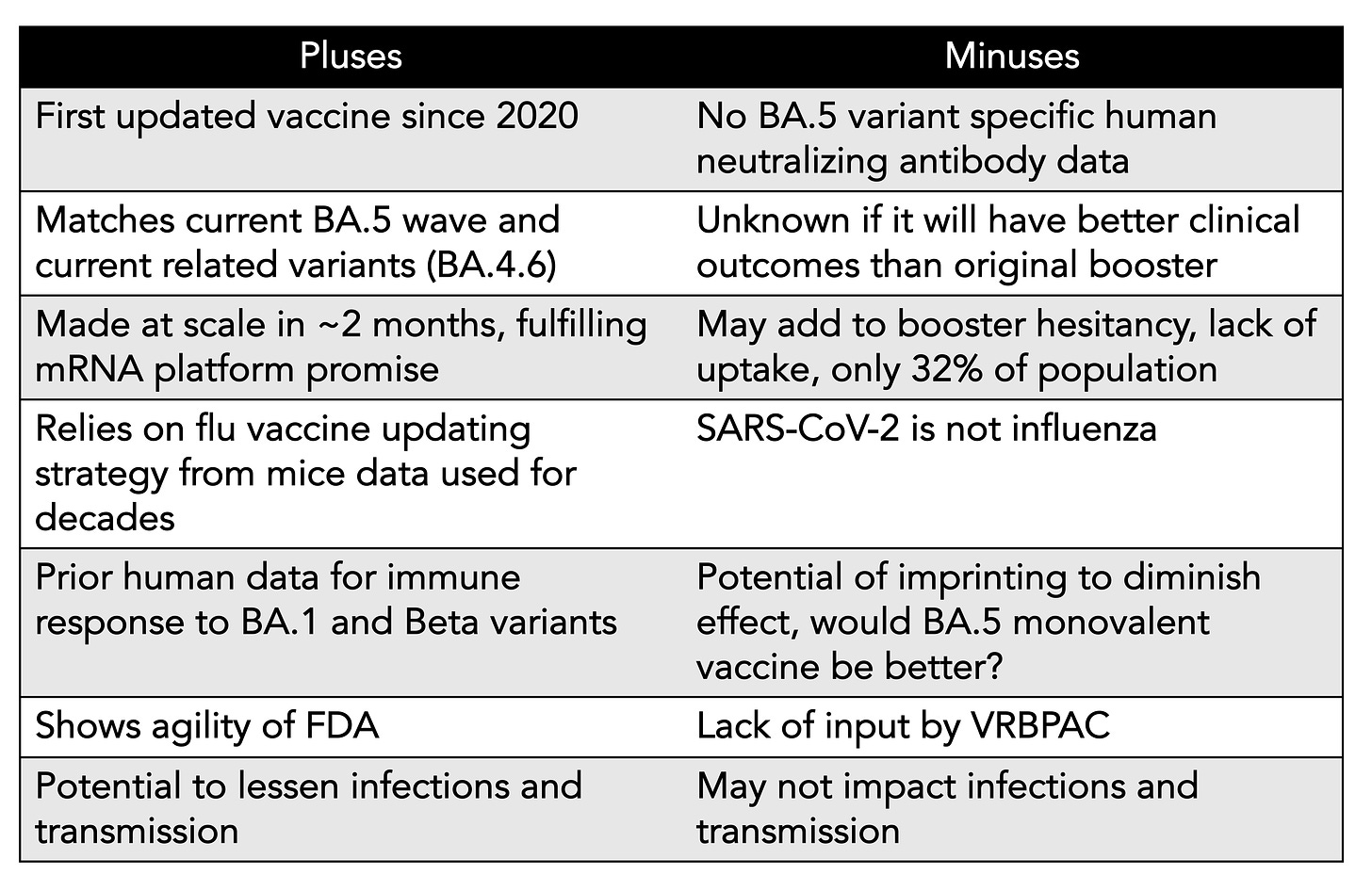

We’ve just learned that in the next few weeks, soon after Labor Day, the first Covid updated vaccine will be available to all Americans age 12+, with over 170 million doses ordered, beginning with the bivalent vaccine (directed to both BA.5 and ancestral strains) from Pfizer/BioNTech, and later, in October, for adults, from Moderna. You’ll see it described as a BA.4/5 vaccine, but the spike protein is identical for these 2 variants and BA.5 is >90% of new cases in the US right now, so I’ve dropped BA.4 in the title of this post and subsequently. There are many considerations going into this plan that I’ve tried to briefly summarize in this Table, and will now get into the data and concerns

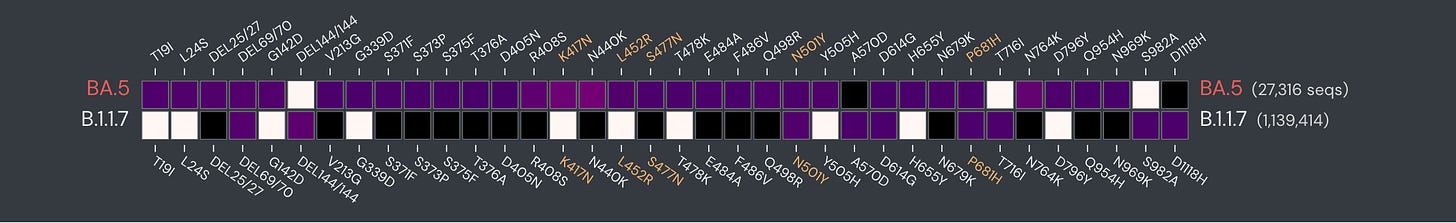

On the face of it, we’re long overdue for an updated Covid vaccine with the marked evolution of the virus since late in 2019. Just take a look at how the spike protein mutations for BA.5 are so dramatically different from the first major variant, Alpha (B.1.1.7).

We do have some data for a BA.1 vaccine (monovalent and bivalent) in people, age 55+, with 3 prior doses of original vaccine, indicating a good induction of neutralizing antibodies vs BA.1 (Figure below, OMI = monovalent, BA.1 only, bivalent = BA.1 and ancestral). As would be expected, the BA.5 response was not as high, and note this is a log-plot. The BA.1 booster is going forward in the UK as their first updated vaccine. Recall that the Omicron variant first surfaced in November 2021, but we didn’t see readiness for a BA.1 booster program for about 7 months.

At the June 28, 2022 FDA Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) review, the decision was to wait for a BA.5 specific vaccine since we were well into the BA.5 wave and had completely passed through BA.1. There are noteworthy differences between these Omicron family variants, as schematically shown below, and biologic properties that I previously reviewed in depth.

At this point, however, there are no data for a BA.5 booster in people. At the same FDA June meeting mice data were presented. As shown below, you can see in a limited number of mice of one strain, who had been given 2 shots of the original vaccine previously, there was a solid BA.5 neutralizing antibody response which was 2-fold higher for the monovalent (OMI, BA.5 only) booster. That’s encouraging compared with the BA.1 shot, but it’s not the same as human data.

Each year the flu vaccine quadrivalent program is updated using mice data, so there’s certainly a precedent for using such data. The totality of data being used to justify going ahead without specific BA.5 neutralization evidence in people stems from both experience with flu vaccines, human data from BA.1 (reviewed above) and a clinical trial with the Beta variant that assessed immune response.

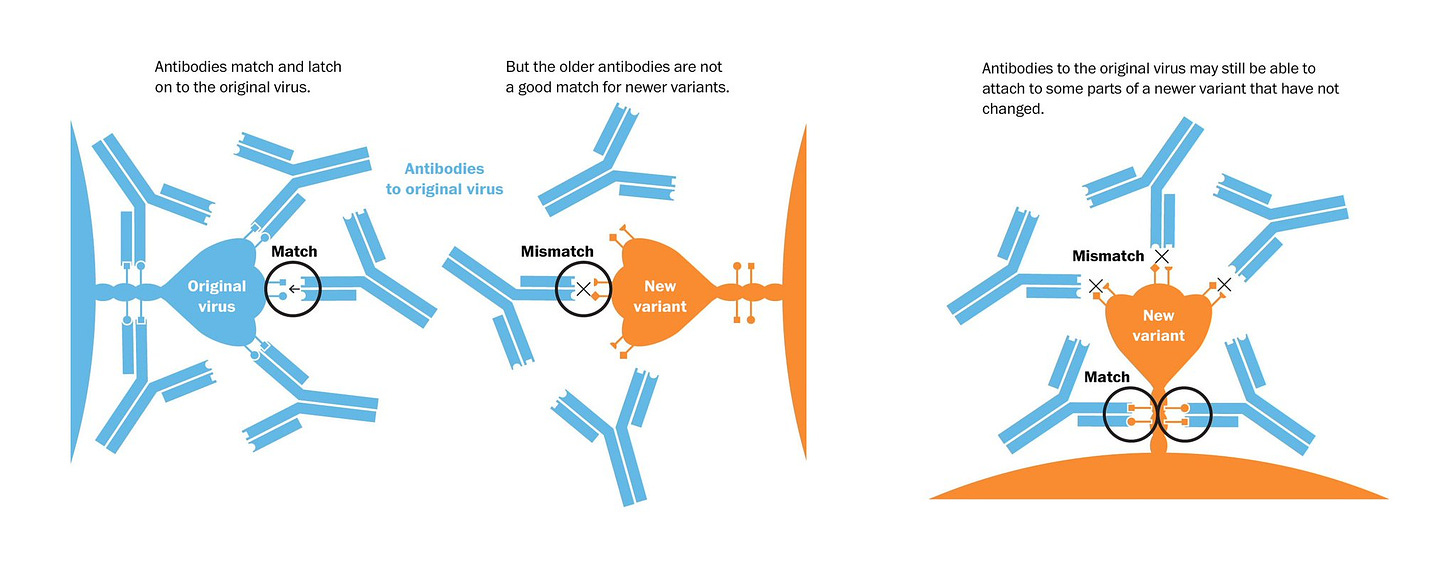

But there’s a concern that it’s not so easy to extrapolate mouse to human for SARS-CoV-2, a virus that’s quite different than influenza. A substantial proportion of people have had 3 or 4 shots of the original vaccine, so there’s the potential for imprinting—that is a preferential revving up of the immune response to what a person was originally exposed to, that is the version of SARS-CoV-2 (also known as original antigenic sin, a poor term since it’s not really a sin, it’s our immune system at work). That concept was just nicely reviewed with an explanatory graphic below.

So we don’t yet know the role of potential imprinting in people receiving the BA.5 booster. Moreover, both Pfizer and Moderna shots are bivalent, whereas the monovalent would be expected to be better, not further inducing an immune response to the obsolete ancestral strain, and with better data in the mouse model (if we’re really embracing data from mice). It’s unclear why a BA.5 monovalent vaccine isn’t going forward at this juncture.

The FDA should be commended for wanting to take an aggressive, expedient approach. BA.5 is the variant now, and the only other co-existing variant in the US at >7% is BA.4.6 which should also be well suited for a BA.5 vaccine. It’s actually striking that in 2 months from the June 28th FDA meeting, there is a BA.5 vaccine booster made at scale. That is finally in keeping with all the excitement about the plasticity of the mRNA vaccine platform, that it could be ideal for rapid updating. We’ve seen that play out now which is exciting. Think pandemic preparedness and management in the years ahead.

But we also need to acknowledge the uncertainties about efficacy and the response from the public. I’m willing to accept that safety will not be an issue based upon the billion of doses of mRNA vaccines that have been given throughout the pandemic, but we’ll await data for that as well.

Efficacy

Our best surrogate marker (pre-Omicron) for efficacy is the level of neutralizing antibodies, from vaccines or infections, as has been established in multiple studies, correlating with protection from severe disease and symptomatic infections (as shown below). But with Omicron and its family of variants, the protection from infections and transmission has dropped substantially.

This is likely tied to the both immune escape and the evolved spike protein’s enhanced binding and fusion (aka fusogenic property) to cells. The problem we have now are “leaky” vaccines, that is the substantially lessened protection from infection and transmission from pre-Omicron. This is central now and must be addressed if containment of the virus is going to be achieved. Not only are we missing human BA.5 neutralization data at this point, but also high levels that are likely to be induced may not achieve the objective of blocking infection and transmission. We know that the recent Omicron family variants, such as BA.5, block interferon, our first line of defense (innate immunity) to a greater degree than pre-Omicron. Antibodies won’t affect that in any way. The question of an imprinting effect, which could diminish efficacy of the BA.5 booster, is also looming. It is likely, however, that neutralizing antibodies will broaden our immune response and protect vs severe disease better, but we don’t even know yet whether another dose (4th or 5th) of the original vaccine booster would be equivalent. Previously it has been shown that with each successive shot of the ancestral vaccine, through a 4th shot, there was broadening of antibody and T-cell immunity. Nonetheless, there appears to be some dropdown in protection vs severe disease with BA.5, along with waning of immunity, so bolstering that level of protection as high as possible would be desirable. That relies on the logical premise that a BA.5 booster will outperform another original vaccine.

On the other hand, the objective of limiting infection and transmission remains unclear, and even if it is actualized, the duration of the effect is uncertain. Recall that with the ancestral strain of the virus through Delta, we had remarkable >90% protection vs symptomatic infections out to at least 4+ months (with a booster), but that all changed once Omicron hit. The Omicron lineages may have evolved to such an extent that shots, no matter how well matched to the spike protein, will not restore the very high level of what we saw vs the original version of the virus.

I still believe the best bet for tackling the infection and transmission challenge is going after a nasal vaccine, which Akiko Iwasaki and I recently wrote about and what we called Operation Nasal Vaccine. That would directly address the problem and we will soon have the readout of efficacy from the first major trial of 4,000 participants, with many more to come in the months ahead—these are booster nasal vaccine program after primary series of shots, with or without a booster shot. They target mucosal immunity, which we have learned is not likely to be attainable via shots.

The Public Perception

A separate (but interdependent) issue from the uncertainties of efficacy is that of public trust. If the new booster campaign is seen as a “rush job” and concerns are heightened that the data is based only from mice, that will certainly not enhance uptake. Framing this further, we have a serious booster lack of uptake in the United States, with only 32% of the population having had any booster shot. That compares quite poorly to our peer countries that are all at least double that rate. The messaging from CDC about boosters—which should be mission critical— was delayed from the get go in the Fall of 2021, and has never gotten on track. For me, it has been the standout disappointment of our CDC’s management of the pandemic, not duly emphasizing the lifesaving benefits (no less reduction of hospitalizations and potential reduction of Long Covid) of boosters (first and second shots) where there is an extraordinary body of evidence to support their need. Just the fact that a 4th shot has marked reduction of mortality in 5 studies compared with a 3rd shot, for cohorts as young as age 50+(including CDC data) but that we have only 11% of people age 50-64 and 26% of Americans 65 and older with a 4th shot tells the story. With the relatively poor uptake of boosters in this country, one could make a case that the need to go to maximum acceleration is reduced. On a side note, this is the last free vaccine that will be distributed by the US government, as the funds have run out and subsequent vaccines, boosters and drugs will be have to be defrayed by other means.

What to Do?

We’ll know much more about the BA.5 bivalent booster in the weeks after the program is launched. Many people will be perfectly comfortable going ahead to get this booster right away and are unconcerned about some of the points I’ve raised. That’s fine. They are quite likely to derive benefit. I am nearly 8 months out from my 4th shot, but will wait to see some data before getting it. Maybe I’m a bit too conservative, maybe too data-driven for my own good.

Most importantly, we need to achieve containment of the virus once and for all, and should not rely only on just the BA.5 booster. The prospects for an effective nasal vaccine are bright. And we’ve got at least 35 different promising virus antigens (epitopes), that we know are the likely substrate for broad neutralizing, variant-proof antibodies. This isn’t influenza, for which a vaccine has never had anywhere close to 95% efficacy, including its nasal vaccine (FluMist), and pill treatments (like Tamiflu) that are nowhere near the impact of Paxlovid. This virus, despite its relentless evolution, has been shown to be more vulnerable. If made a priority, pan-sarbecovirus vaccine candidates could move forward with multiple antigens from what has now accrued to a long list, both in and outside the spike protein. We’ve endured what will soon be 3 years, have seen millions of deaths, and likely at least 10X the number of people suffering Long Covid. We should pull out all the stops to get ahead of the virus, which includes blocking infections and transmission. Perhaps the aggressiveness of the imminent roll out the BA.5 vaccine reflects a new attitude, which is good. But that’s just one dimension of the efforts that can and should be pursued to prevail.