The Updated Red Meat Story

Two new reports shed light on potential risk and mitigation

I haven’t been a red meat eater for over 4 decades. When I’m at a dinner party or gala event, it’s frequently awkward to wait for the vegetarian or seafood request to show up while all the others have their plates in front of them. Or when they are looking at me as a cardiologist and acting sheepish that they are about to eat a steak. But I fully understand that the majority of the population (some ~70%) enjoys and many often crave red meat. There are two new reports, one zooming in on changes in the gut microbiome, and the other on a link between cognitive function and red meat, that are the main topic for this edition of Ground Truths. Before getting into these new studies, a bit of background.

Mechanistic Background

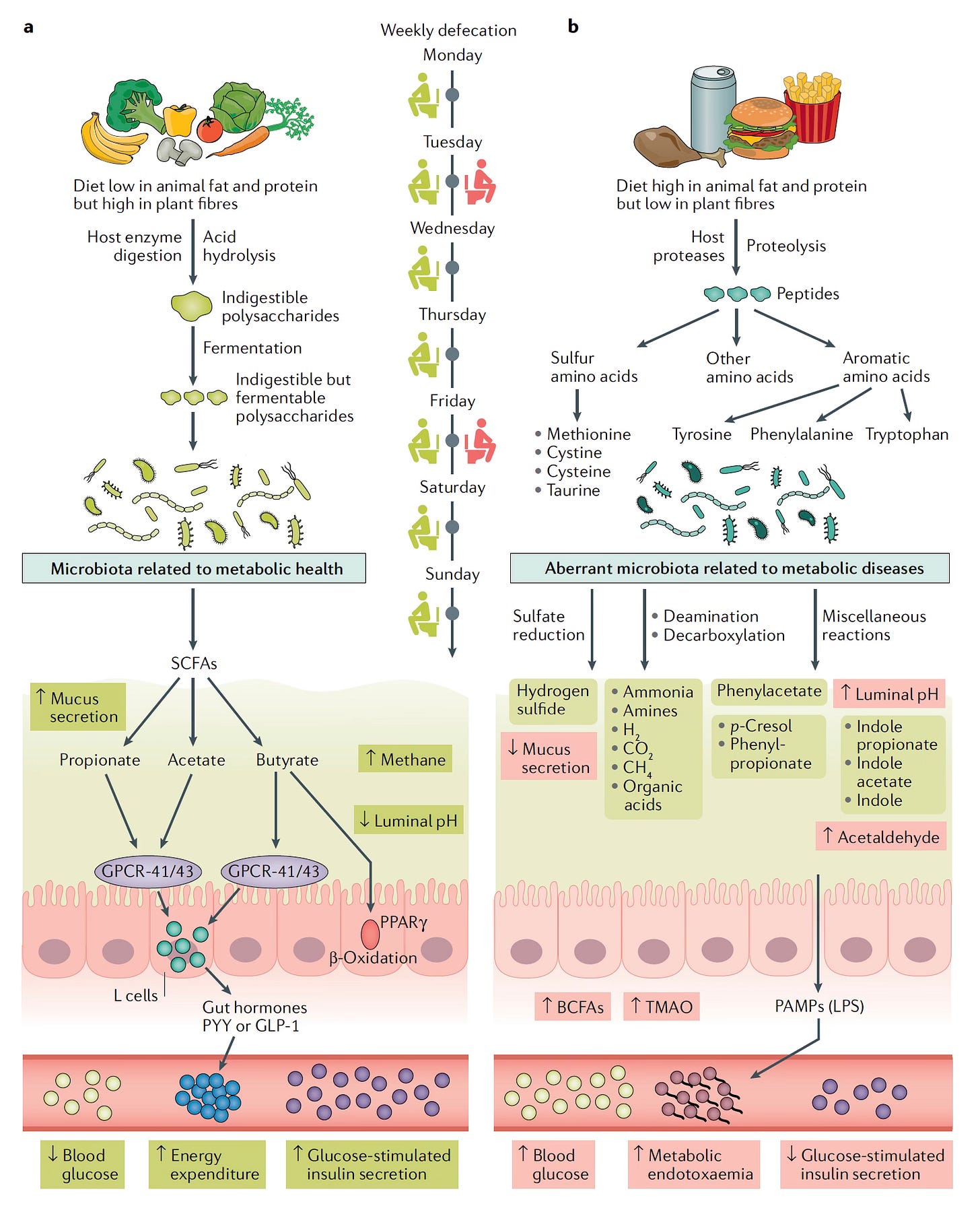

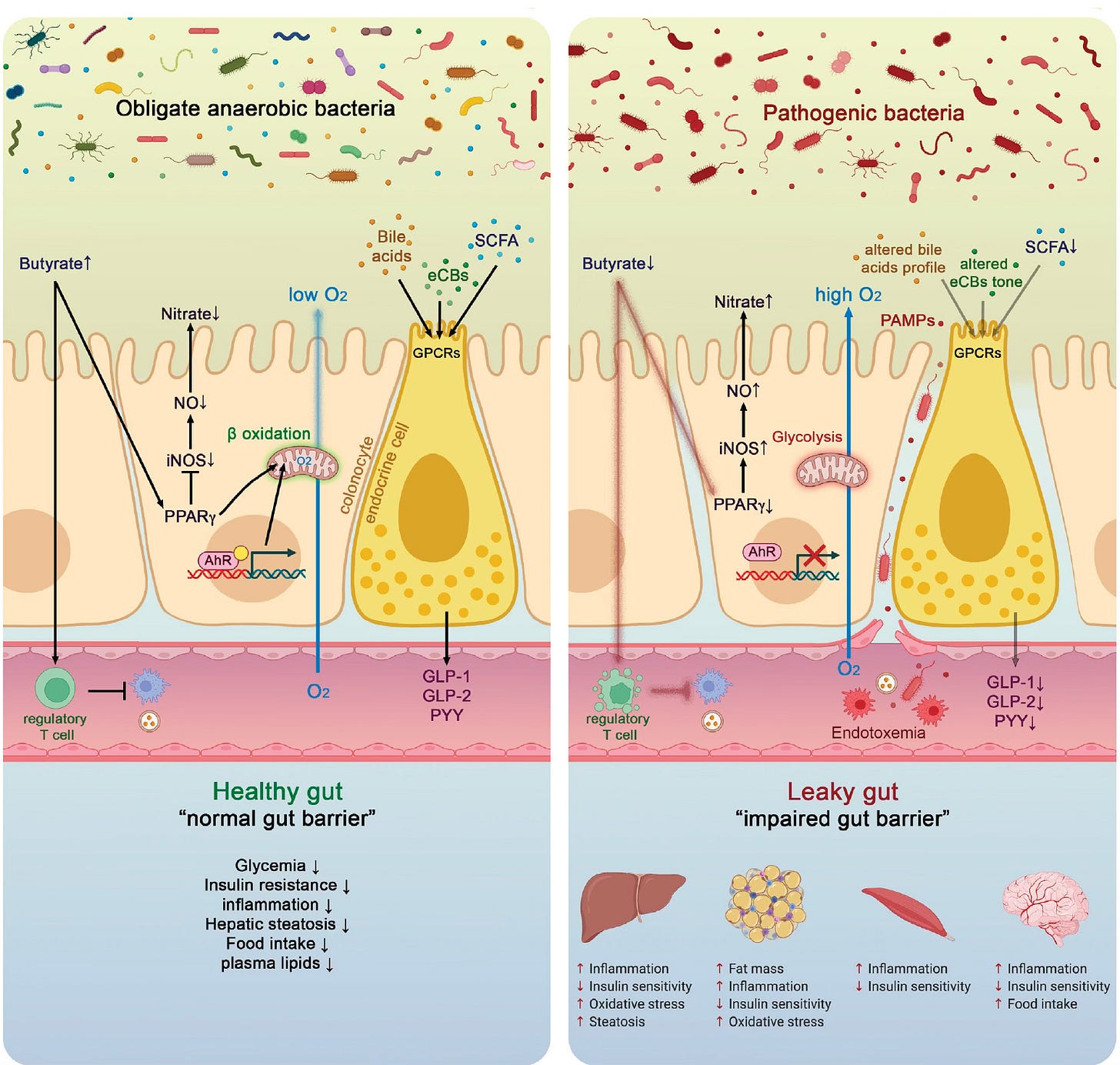

In contrast to plant-based diets that promote a healthy gut lining (mucosa), non-inflamed gut barrier, via indigestible polysaccharides, polyphenols, and promotion of short chain fatty acids (SCFA, such as propionate, acetate, and butyrate), red meat intake reduces SCFAs, can induce a leaky mucosa, leads to gut microbiome production of trimethylamine N-oxide(TMAO), which has been strongly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and potentially also with higher risk of colon cancer. High animal fat ingestion also promotes branched chain fatty acids (BCFAs) and pathogen-associate molecular patterns (PAMPs) as seen below. And yes, the change in transit time from these different diets generally affects weekly defecation.

Also note the favorable effect of plant-based intake on gut hormones (such as GLP-1) for glucose regulation/insulin sensitivity and in the Figure below (left panel, middle portion) on immune system crosstalk, such as the impact of SCFAs to stimulate Treg cells that reduce inflammation.

Epidemiological Background

There are many studies that have looked at red meat intake and outcomes, with the shortcoming that most of these rely on self-reporting, typically via questionnaires or food diaries.

In a prospective, observational study of 53,000 women and 27,000 men with 8-year follow up there was an association of read meat ingestion with ~10% increased risk of all-cause mortality, and a bit higher with processed meat intake. In another prospective study of nearly 30,000 participants, unprocessed red meat intake was linked to higher all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease, at a similar magnitude as the small hazard ratio in the prior study. Yet another prospective study from a ~71,000 participant cohort in Japan that compared plant and red meat intake found reduced risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality as a function of higher plant intake, and reduction of risk for red meat intake when substituted with plant-based foods.

Those results were contradicted in the only randomized trial (of 12 published) that was deemed of acceptable quality. It (Women’s Health Initiative) enrolled nearly 49,000 women and found little evidence for red meat association with cardiovascular or cancer risk, with many issues surrounding that interpretation, such as the focus of the trial was reduction of dietary fat intake, not red meat per se. A systematic review of 56 cohort studies also did not find definitive evidence of harm.

On the other hand, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) previously classified consumption of processed meat as “carcinogenic to humans” and consumption of red meat as “probably carcinogenic to humans” (with respect to colon cancer] based on a meta-analysis of 10 studies with a 17% increased risk per 100 g per day of red meat and an 18% increase per 50 g per day of processed meat.

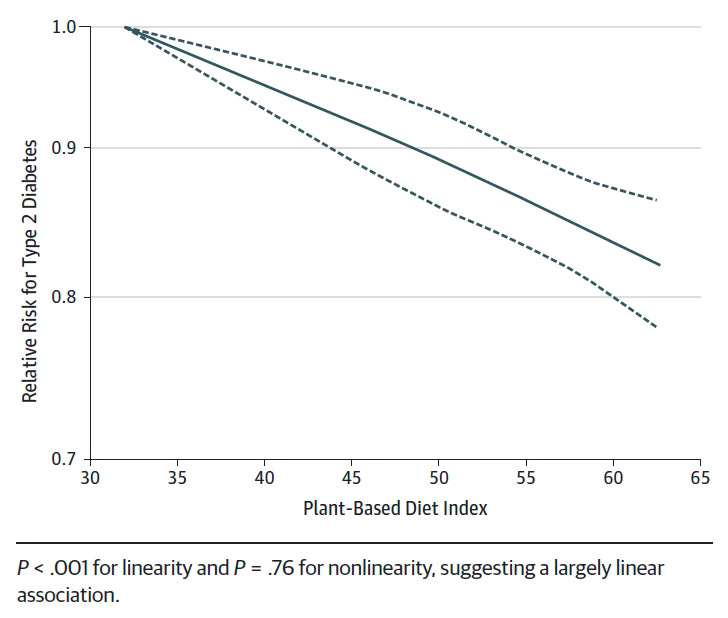

The association of benefit of plant-based diets with improved survival, less cardiovascular events and less cancer has been seen in both a systematic review and meta-analysis of 24 cohorts for reducing animal-based with plant-based foods.

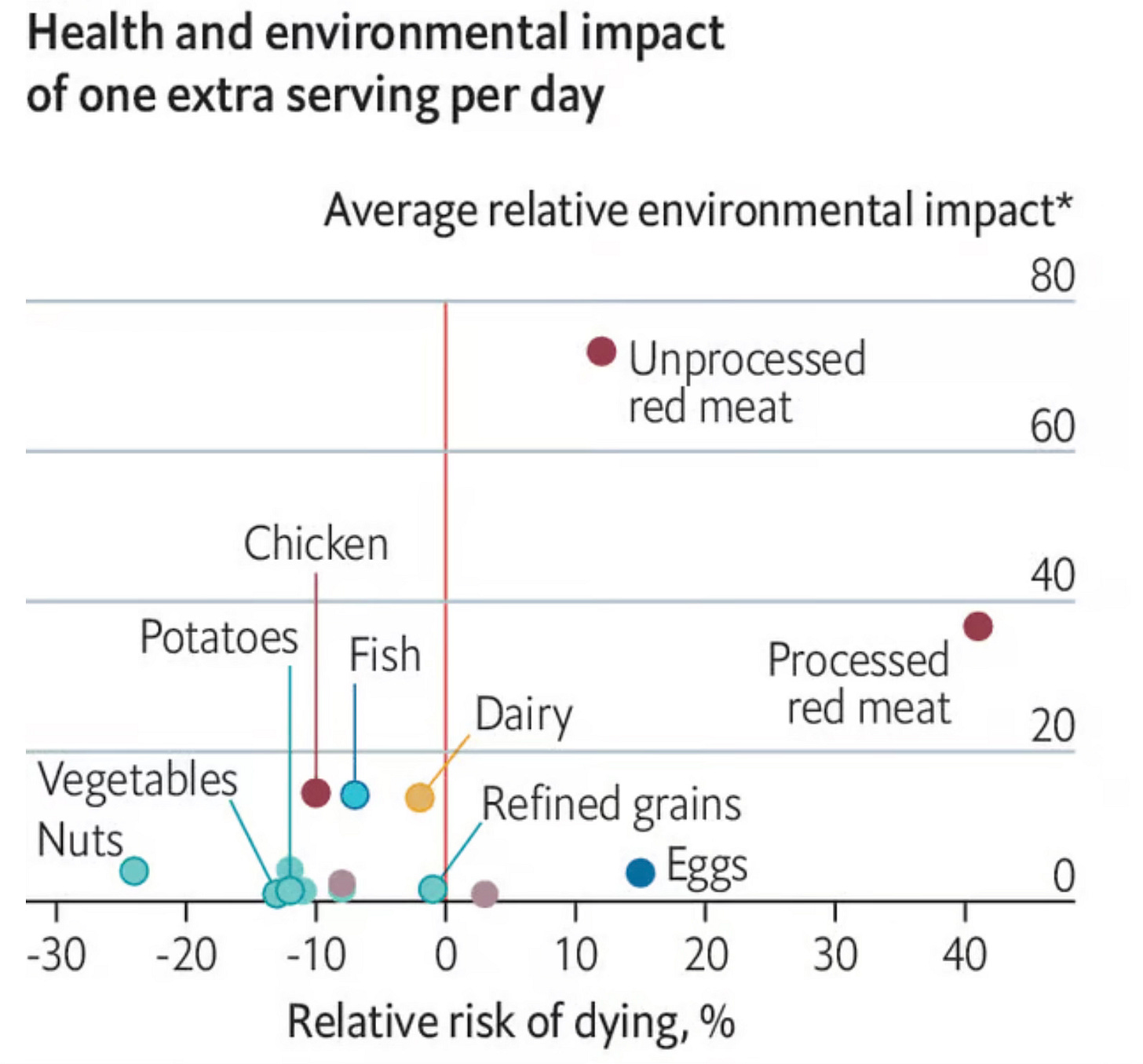

The preponderance of data on red meat intake—both processed and unprocessed—was summarized in a report by Clark and colleagues in PNAS for both relative risk of dying (all-cause mortality) and environmental impact (y-axis, below), with the higher the average relative environmental impact (AREI) index, the more detrimental. The graph shows how foods associated with improved outcomes were also associated with low environmental impacts.

There are many other publications on red meat and plant-based diets, but I hope the ones reviewed here give you a sense of what has been published, with some mixed results and uncertainties.

The New Reports

The Diet-Gut Microbiome Signature Study

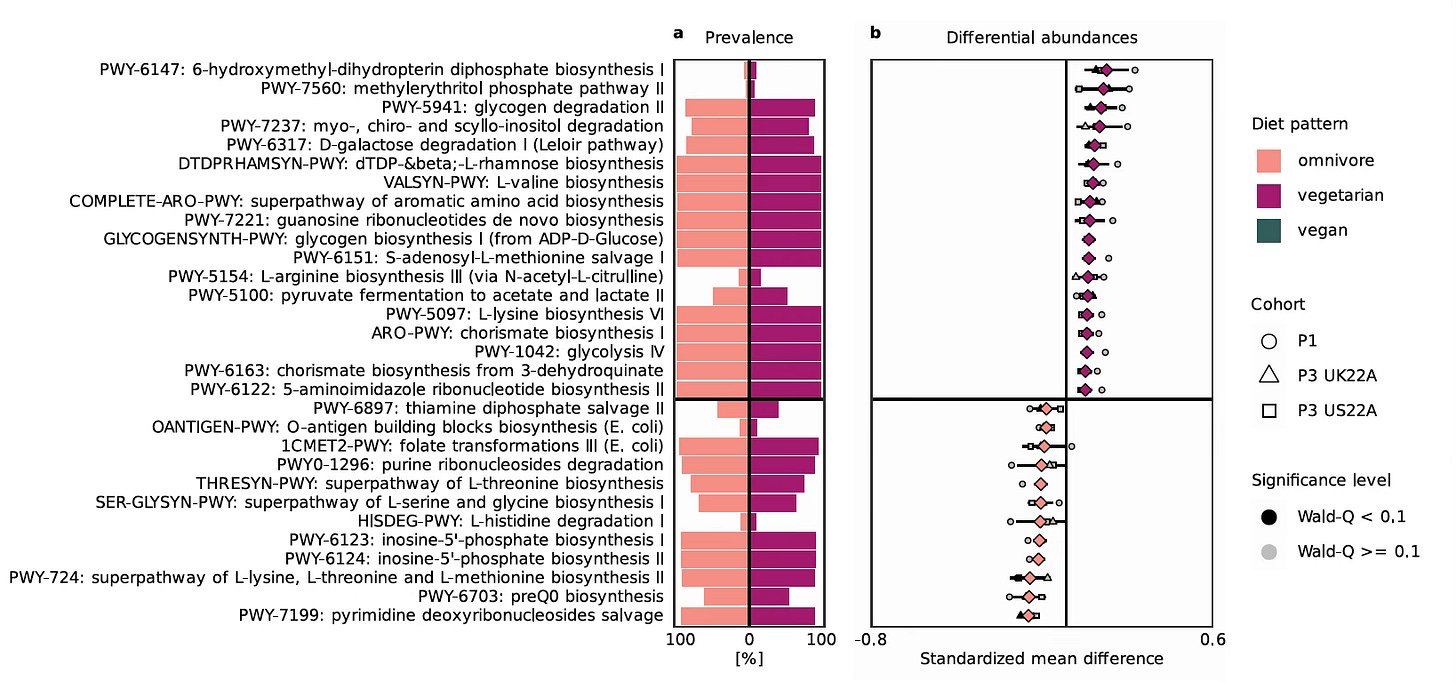

In a new paper by Fackelmann and colleagues in Nature Microbiology, the gut microbiome (using shotgun metagenomic sequencing) was assessed in over 21,500 participants from 5 different cohorts for three diet patterns: omnivore, vegetarian, and vegan. Overall there were 656 vegans, 1,088 vegetarians and 19,187, the vast majority, were omnivores. The 3 diets had microbial profiles—species-level genome bins (SGBs)— that differentiated them. The omnivore microbiome was driven by red meat and the primary microbes were Ruminoccous torques, Alistipes putresinis and Bilophila wadsworthis—microbes associated with inflammation and adverse cardiometabolic health outcomes, previously linked to inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. In contrast, the vegan microbial signature featured Lachnospiraceae, Butyricicoccus sp., and Roseburia hominis, all of which have had the opposite effect of reducing inflammation and promoting cardiometabolic health, in part by producing SCFAs like butyrate. The vegetarian diet SGB was in between these profiles. Biologic pathway analysis of the microbiome signatures showed marked difference between the omnivore and vegetarian diets (Figure below).

A key finding was that omnivores who are more plant-based foods shifted their gut microbiome profile to be favorable, more like the vegan and vegetarian participants.

The Red Meat Dementia and Cognitive Decline Study

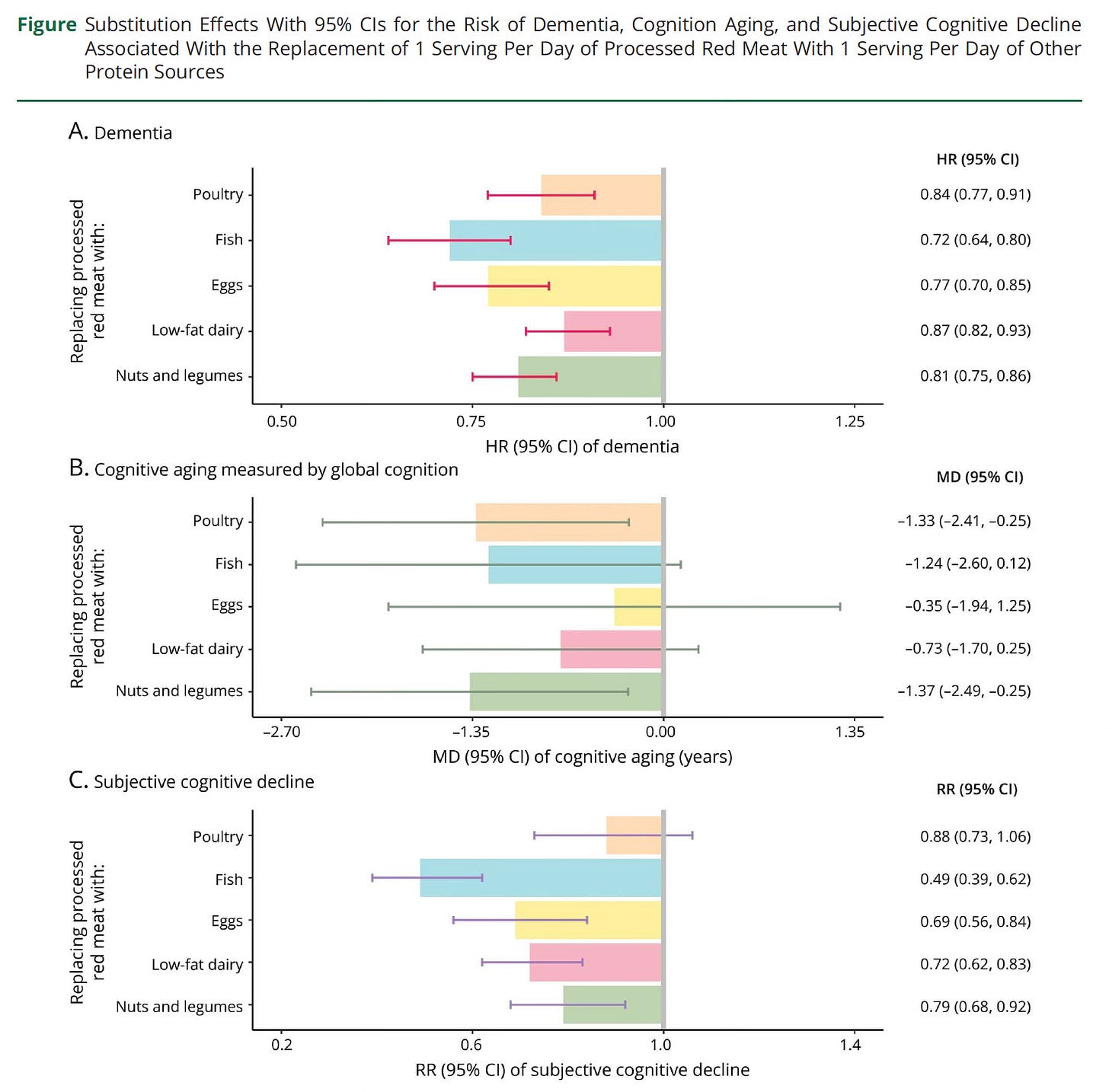

In the journal Neurology, Li et al provided results for prospective follow-up for almost 134,000 participants with a mean age of 49 years at enrollment for dementia analysis. There was also objective cognitive function assessed in over 17,000 women participants, along with subjective cognitive decline in ~44,000 female participants. Processed red meat intake, as partitioned by >0.25 servings per day vs < 0.10 servings per day, was associated with a 13% increase risk of dementia, 14% higher risk of subjective cognitive decline, with a dose-response relationship. Unprocessed red meat (1 serving per day vs <0.50 serving/day) was associated with a 16% elevated risk of subjective cognitive decline.

But, notably, the increased risk of dementia or cognitive decline was mitigated by replacing 1 serving per day of processed red meat with nuts or legumes (Figure, (see other healthier protein source substitutes) with a 19% reduced risk of dementia and 21% lower risk of subjective cognitive decline

Synthesis

The mechanistic work on high consumption of red meat vs plant-based diets provides a solid foundation for concern for cardiovascular and cancer (particularly colon) risk. But the epidemiological studies reviewed here (and 1 randomized trial that is very difficult to interpret for red meat effect) are, overall, more indicative of a small risk that is higher for processed red meat. These studies have the major limitation of being observational and relying on the participant’s memory for food intake, which often changes over time, and represents a very subjective and suboptimal data source.

The new study using gut microbiome evidence of distinct signatures takes this more into the objective realm. However, the microbial species tagged to red meat from the omnivore diet or the plant-based diets were not directly assessed for health outcomes, but instead required extrapolation from prior reports on cardiometabolic health or biomarkers of inflammation. We need studies that directly provide objective data like gut microbiome profile and follow-up for clinical outcomes. Use of organ clocks, as I previously reviewed, high-throughput proteomics, and Mendelian randomization would help. The cause and effect relationship for red meat needs to be established and quantified rather than characterized by various associations.

The finding of red meat intake association with dementia, brain aging, and subjective cognitive decline adds to the body of evidence for cardiovascular and cancer links. However, it, too, is limited from being based on observational data and not definitive.

But there is one thematic message from the new reports. Eating more plant-based foods titrates the risk of red meat intake, at least as reflected by the gut microbiome profile and the lowered risk of adverse clinical outcomes. That takes us back to Michael Pollan’s wise quote: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” Red meat eaters would likely do well by eating more plant-based foods and substituting some of that intake with other healthier protein sources.

********************

Join me for a live zoom conversation on Wednesday, January 29 at 10 AM PST

Here’s the link. We’ll discuss any biomedical topics of interest!

Thanks for reading and subscribing to Ground Truths.

If you found this interesting please share it!

That makes the work involved in putting these together especially worthwhile.

All content on Ground Truths—its newsletters, analyses, and podcasts, are free, open-access.

Paid subscriptions are voluntary and all proceeds from them go to support Scripps Research. They do allow for posting comments and questions, which I do my best to respond to. Many thanks to those who have contributed—they have greatly helped fund our summer internship programs for the past two years.

Great article, thanks. A question that would be important to know: Is there is a difference between exposure to red meat from the uniquely American industrial style meat production vs. from wild game or traditional pasture raised beef or lamb? Most of the rest of the world raises beef and lamb in remarkably different environments than we do, and with a much different diet for the animals themselves.

Duration of exposure is the missing factor in all these studies. Lifespan has increased since prehistoric times, and considerably so in recent centuries and decades. Perhaps exposure mattered less when lifespan was 30 or 40; it's now 70, 80, and 90 years and congruent with a known decline in immune system function with aging.