When the Breakthrough Obesity G-Agonist Drugs Exceed Expectations

The expanding GLP-1 family of drugs and their expanded potential use cases

Back last December I wrote about the The New Obesity Breakthrough Drugs, and specifically the striking results in randomized trials for semaglutide (Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro) for weight loss, their putative mechanism(s), while also emphasizing their very high cost, lack of plan for successful weaning, and exacerbation of health inequities. Since then, the landscape of G-agonists has evolved considerably with respect to both new drugs (triple agonists) and clinical impact beyond obesity per se. In this issue of Ground Truths, I’ll try and review this rapidly advancing field and where we’re headed.

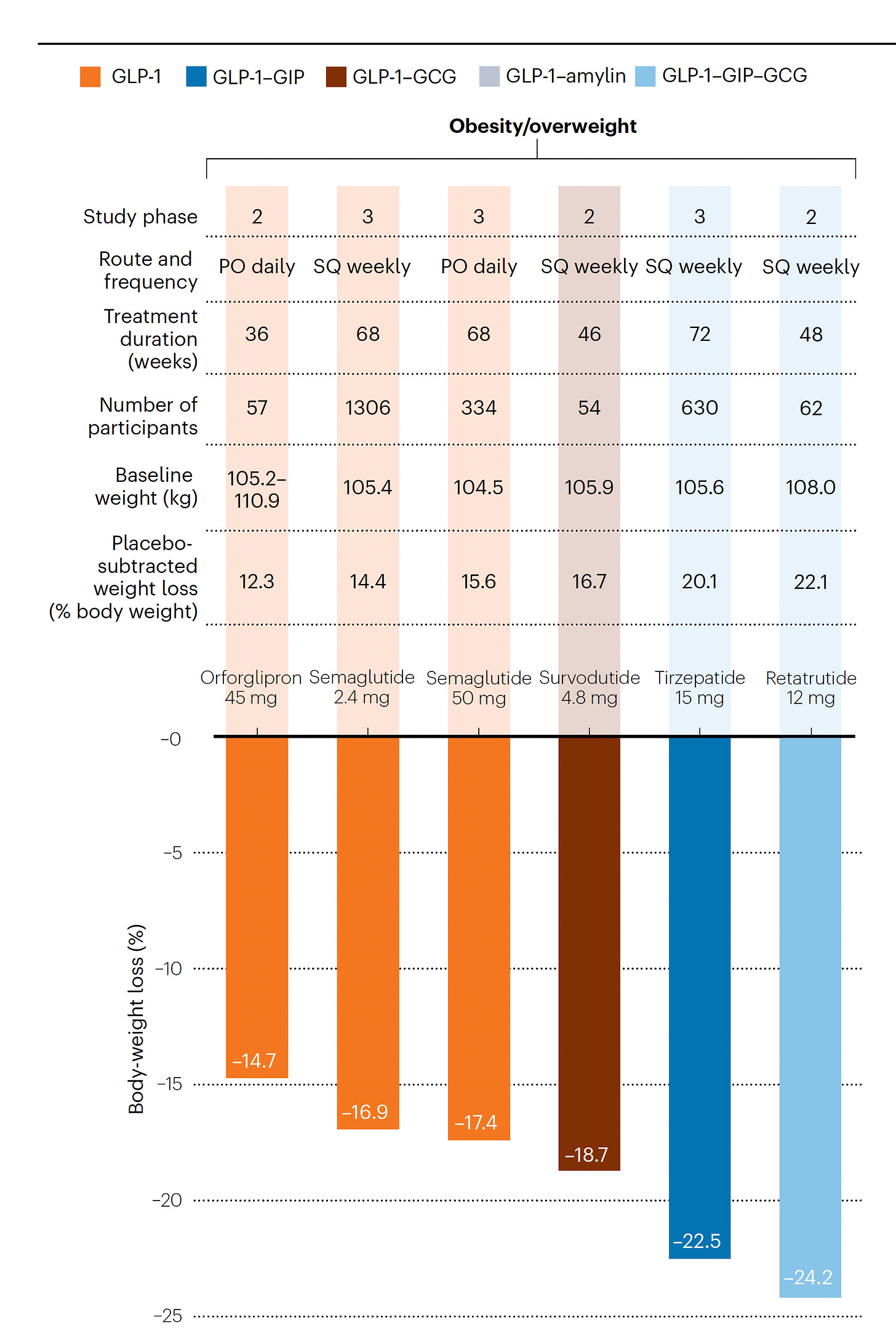

The First Triple G-Agonist

In their Nature Medicine editorial this week “A Revolution in Obesity Treatment,” Lingvay and Agarwal highlighted the results of the first triple incretin-like drug—retatrutide—with completed Phase 2 randomized trials. What is meant by incretin-like and why triple? Incretins are gut secreted hormones, G-protein-coupled receptor peptides, that include glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon (GCG). Each of these 3 incretins have somewhat different effects, both at the gut level and via the brain, regarding reduced appetite, increased energy expenditure, nutrient storage and substrate utilization, insulin secretion, promotion of satiety, delay of gastric emptying, or reduced systemic inflammation. Incretin-like drugs mimic these hormones, and while we do not have any head-to-head trials, you can see from the informative Figure below, summarizing best results of this family of drugs to date, moving from single agonist GLP-1 to double and then triple (GLP-1-GIP-GCG), there is incremental body weight loss.

As in the prior GLP-1 trials reviewed, the GI side effects early that include vomiting, diarrhea, nausea, and constipation, occur in about half of the participants with initial dosing. At the highest dose, 16% of participants taking the triple agonist had to discontinue the drug due to gastrointestinal side-effects. None of the drugs yet have clinical trials with more than 2-year follow-up which leaves us with questions as to micronutrient deficiencies and risk of loss of muscle mass and bone density. In one study with body composition assessed for a subgroup, lean body mass (which includes muscle and bone) accounted for nearly 40% of the weight lost.

The 2 retatrutide Phase 2 trials are summarized graphically below, links here and here. Marked improvement in HbA1c was seen along with even more weight loss among participants with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2. In a subgroup of 98 people with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in the latter trial, liver fat content normalized in 90% at the highest dose of retatrutide. Note the lack of a plateau of weight-loss effect in these trials at 36 and 48 weeks, respectively.

Also noteworthy earlier this month was the publication of a Phase 2 randomized trial in 272 participants without diabetes of orforglipron, an oral GLP-1 agonist, which achieved a 14.7% weight loss (placebo-adjusted 12.3%) at the highest dose

With that brief review of the latest trials and drugs, let’s turn to clinical outcomes, for which most are taking us back to single agonist—GLP-1—drugs.

Reduction of Major Cardiovascular Events

The SELECT trial of semaglutide (vs placebo) will be presented in November at the American Heart Association. It enrolled 17,605 participants, average age 61.6 years, who were obese or overweight (BMI average = 33 kg/m2) without diabetes but with prior heart attack, stroke or peripheral artery disease. Two-thirds of enrollees had abnormal HbA1c (5.7-6.4%). 24% had heart failure at baseline and about half were heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The participants came from 41 countries (6 continents) via 804 clinical sites and enrolled from October 2018 to March 2021, such that we’ll have nearly 5-year follow-up data from the early enrollees. On August 8th, the company had a press release to announce that the primary endpoint—cardiovascular death, heart attack or stroke—was reduced by 20%. We eagerly await the full publication and details of this groundbreaking trial that changes the story from weight loss to protection from major cardiovascular events in people at high-risk.

Reduction of Heart Failure

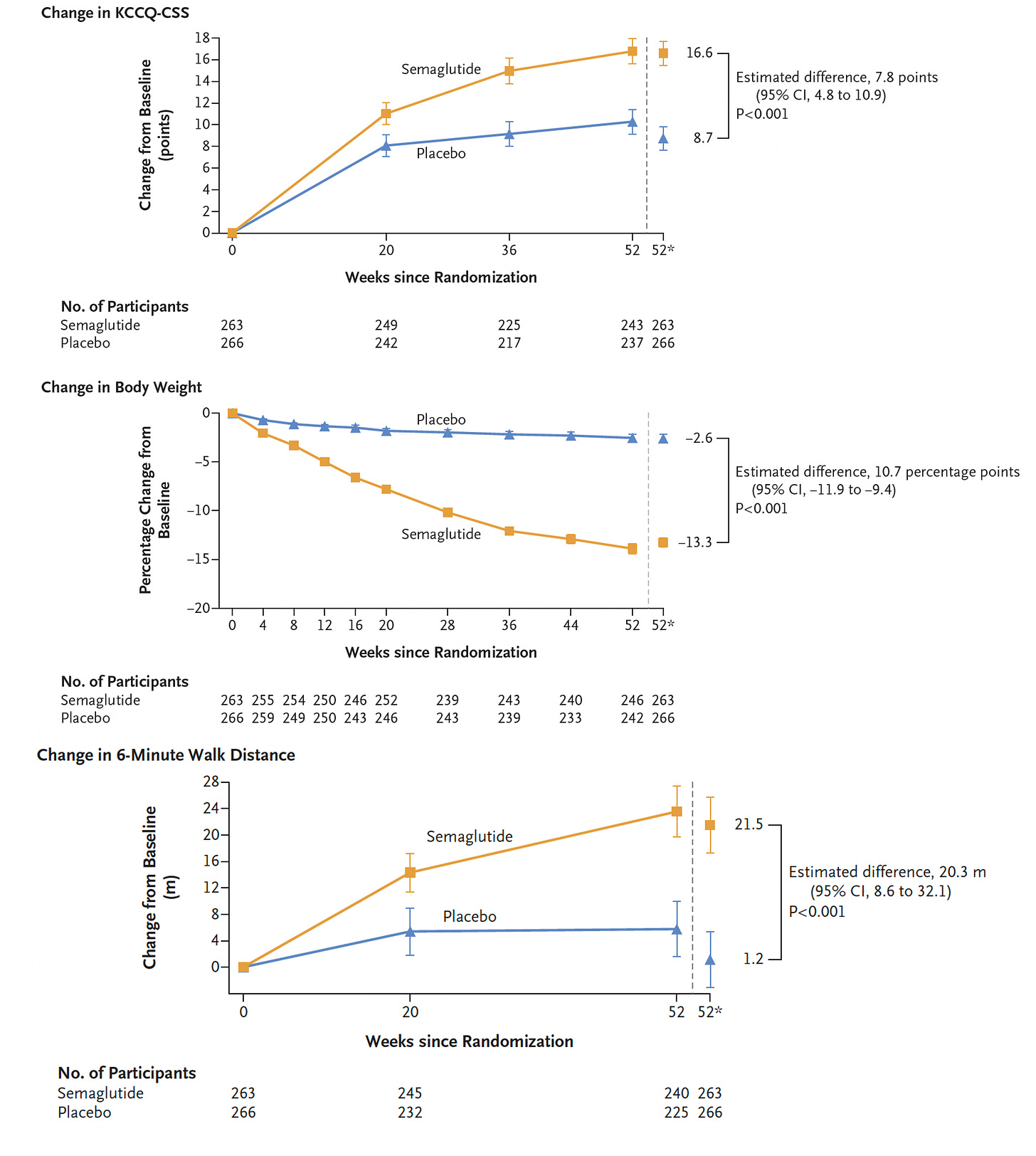

About half of people with heart failure have preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), so rather than diminished pump function it is the impaired ability for the heart to relax and fill (diastolic dysfunction) that accounts for their symptoms. In a randomized trial of semaglutide 2.4 mg vs placebo for 1 year, 529 participants with HFpEF with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2, there was a very large reduction in symptoms, improvement in exercise function in the GLP-1 drug assigned group. As seen below, the change in the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire clinical summary score (KCCQ-CSS), reflecting physical limitations and symptoms, nearly doubled. Body weight reduction was 10.7% correcting for the small weight loss in the placebo group. The 6-minute walk test from baseline improved over 20 meters in the treatment group but only 1 meter in the placebo group.

A subgroup analysis by weight reduction iced the case for proportionate benefit of symptom relief and less inflammation (by biomarkers) as a function of weight loss

These are striking results for people with HFpEf given the only other drugs that have thus far shown benefit are the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. Moreover, it makes the case that obesity (and its metabolic consequences) is the underpinning of HFpEF. The reduction of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was 15% more than placebo, this being an important change in a surrogate marker for improving heart function. It’s a small trial with only 1-year follow up and lacking hard endpoints such as hospitalization or cardiovascular deaths, but the results for symptomatic relief and gain in physical activity are certainly very encouraging.

Potential Role in Early Type 1 (Autoimmune) Diabetes

A few weeks ago Dandong and colleagues published a series of 10 patients with recent diagnosis of autoimmune diabetes (with autoantibody assays), a HbA1c level of 11.7% and fasting C-peptide (reflecting insulin production) of 0.65 ng/ml. All were prescribed basal and meal (prandial) insulin. After treatment with semaglutide, 7 of the 10 patients got off insulin completely and the other 3 no longer required prandial insulin. The HbA1c fell to 5.7% at 1 year follow-up and the C-peptide increased 62% to 1.05 ng/ml. The authors compared these results to 4 historical published reports of early-onset Type 1 diabetes without GLP-1 drug intervention, and all those cohorts had increased HbA1c over time. The fasting C-peptide increase reflects substantial intact pancreatic beta-cell reserve to produce insulin. Whether this can be maintained with longer follow-up is unknown. But what is particularly intriguing is to combine this intervention with a drug that knocks down the self-directed T-cell effect and significantly delayed the onset of Type 1 diabetes with such drugs as teplizumab shown effective in a small trial of at-risk relatives. To put it simply, if a GLP-1 or triple G-agonist even got rid of insulin requirement in 1 out of 10 new onset Type 1 diabetics, that would be a very big deal.

Restoring Impaired Associative Learning

In a recent study in Nature Metabolism, Hanssen and colleagues showed that a GLP-1 drug (liraglutide), in a small trial (N=24 participants) of people with insulin resistance, with a single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled crossover design, with functional brain MRIs, that 1 dose normalized impaired learning of sensory associations, supporting that “metabolic signals profoundly influence neuronal processing.”

Reduced Alcohol Drinking and Potential Anti-addiction Drug Effects

In the experimental model, Chuong and colleagues published in JCI the impact of GLP-1 drugs to inhibit alcohol intake. Other studies in rodents indicate parallel effects for other addictive drugs including nicotine, opioids, and stimulants. Not just drugs, even gambling may be affected. But now this is increasingly being noted in people and prompted The Atlantic’s Sarah Zhang to publish a piece entitled "Did Scientists Accidentally Invent an Anti-addiction Drug?”

The studies in people are limited, such as cases series for cocaine addiction and a small randomized trial for alcohol use disorder, which included fMRI. Clearly the brain/central nervous system effect of these drugs is gaining traction and considerable interest.

Other New Stuff: The Genetics of G-Agonists

In a seminal study of the genomics of glucose regulation in nearly 500,000 people, specific coding variants of the GLP-1 receptor (GLP1R) were associated with potential GLP-1 drug response. That work was furthered by another very recent paper specifically dedicated to GLP-1 receptor variants, with functional analysis of 60 loss-of-function GLP1R variants. The defective insulin secretion and increased adiposity linked with reduced cell surface GLP-1 receptor expression helps our understanding for how these G-agonists work. To note, with the G-agonists, GIP receptors in the brain may respond differently than those peripherally, with less GI side effects.

A Discoverer Shortchanged

In Science this month, there’s a profile of Professor Svetlana Mojsov, a chemist at Rockefeller University, who published key papers on GLP-1 including a landmark one in 1986. Of 3 men who were recognized for the prestigious Gairdner award (Habener, Drucker and Holst) Habener said “I’m on Svetlana’s side, I really feel sympathetic. I wish there was something I could do.” With GLP-1 and G-agonists having the look of the hottest drug class in medical history, it is notable that a woman scientist and co-discoverer was sidelined from recognition. Do Rosalind Franklin and so many others ring a bell?

Bottom Line

Despite some dizzying progress for this class of drugs, there are still so many unknowns (besides lack of explainability as already touched on). For example, why do people with diabetes lose less weight than obese, non-diabetics (first Figure from this post expanded to show the difference for the various drugs)?

For that matter, how precisely do these drugs work? As Aaron Carroll penned in a recent New York Times oped, like antidepressants, “medical treatments should not be dismissed just because we don’t fully grasp their mechanisms.” This lack of explainability (As Dr. Carroll wrote: “I’ve lost 15 pounds in the last five weeks, and I’ve done it with ease. It can’t just be because I’m eating much less, because I haven’t reduced my caloric intake that much. But like everyone else, including scientist, I have no idea why these drugs work so well.”) is akin to large language A.I. models like GPT-4—we really don’t know how they work. A critical point that Al Gore made in our recent podcast. (“We have no idea”).

Beyond these concerns, there’s now a family ranging from single to triple G-agonists and we have no idea how such potent interventions should be optimally used. More importantly, how can we get people taking these drugs weaned from them? It appears the drug manufacturers of G-agonists have no interest in this vital objective, without any ongoing prospective clinical trial efforts directed at cessation of their drugs without reversal of weight gain and assorted benefits. There is no reason to wonder about why this is the case, of course, but something has to be done.

I won’t again review here the issues of exorbitant costs, reimbursement coverage by insurers, health inequities, and lack of availability, since these were previously summarized.

The G-agonists are moving to become the most successful drugs in medical history, eclipsing other widely used and transformative drugs like statins. Their salutary and what appears to be marked impact— beyond losing weight— is getting validated in ways not fully anticipated, affecting cardiovascular outcomes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and perhaps substance and behavioral addiction. In short, while there’s still so much that needs sorting out, we’ve got a breakthrough family of drugs that are already exceeding lofty expectations. Stay tuned!

Thanks for reading and subscribing to Ground Truths. Please share if you found this informative.

NB: I have no relationship with any manufacturer of a GLP-1 or G-agonist.

Reminder: All proceeds from Ground Truths goes to support Scripps Research.

It will not surprise anyone who follows big Phrma that the US is the ONLY country where these drugs are extremely expensive. USA= $936. Second most expensive is Japan at $169. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/prices-of-drugs-for-weight-loss-in-the-us-and-peer-nations/

With such a large patient target population that will benefit from these G-agonists, they should be on the list of drugs requiring price negotiation by Medicare. Second, with funds from multiple NIH Institutes, research should be encouraged into the gut-brain connection affected by these drugs. Perhaps, this research may provide insights into how to wean patients from these drugs without losing all their benefits.