“These two ghosts in the machine, the mind and the tumour, whispering to each other in the dark recesses of the brain, engage in a conversation that could be well worth eavesdropping on.” —George Ibrahim and Michael Taylor

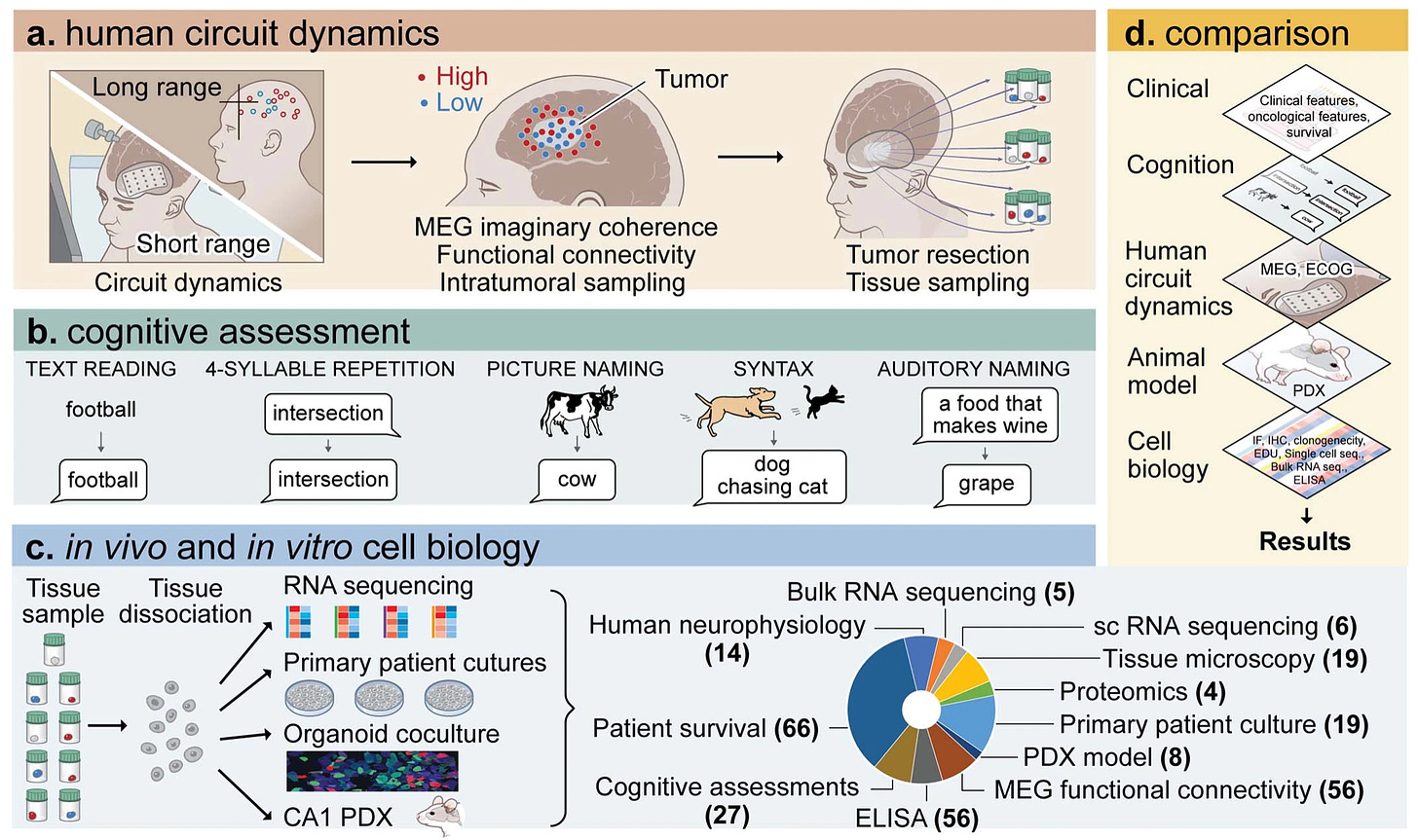

A fascinating study was published at Nature this week: patients with the most aggressive, treatment-resistant, and deadly form of brain cancer—glioblastoma multiforme, glioma—have bidirectional interactions between the tumor and their mind. This is an elegant study involving awake patient brain recordings during surgery with cognitive testing, parallel animal testing, cultured cells in organoids (“brain in a dish”) and extensive biologic characterization as summarized in this graphic below. Surprisingly, despite its importance, it has not been covered by any major media outlet.

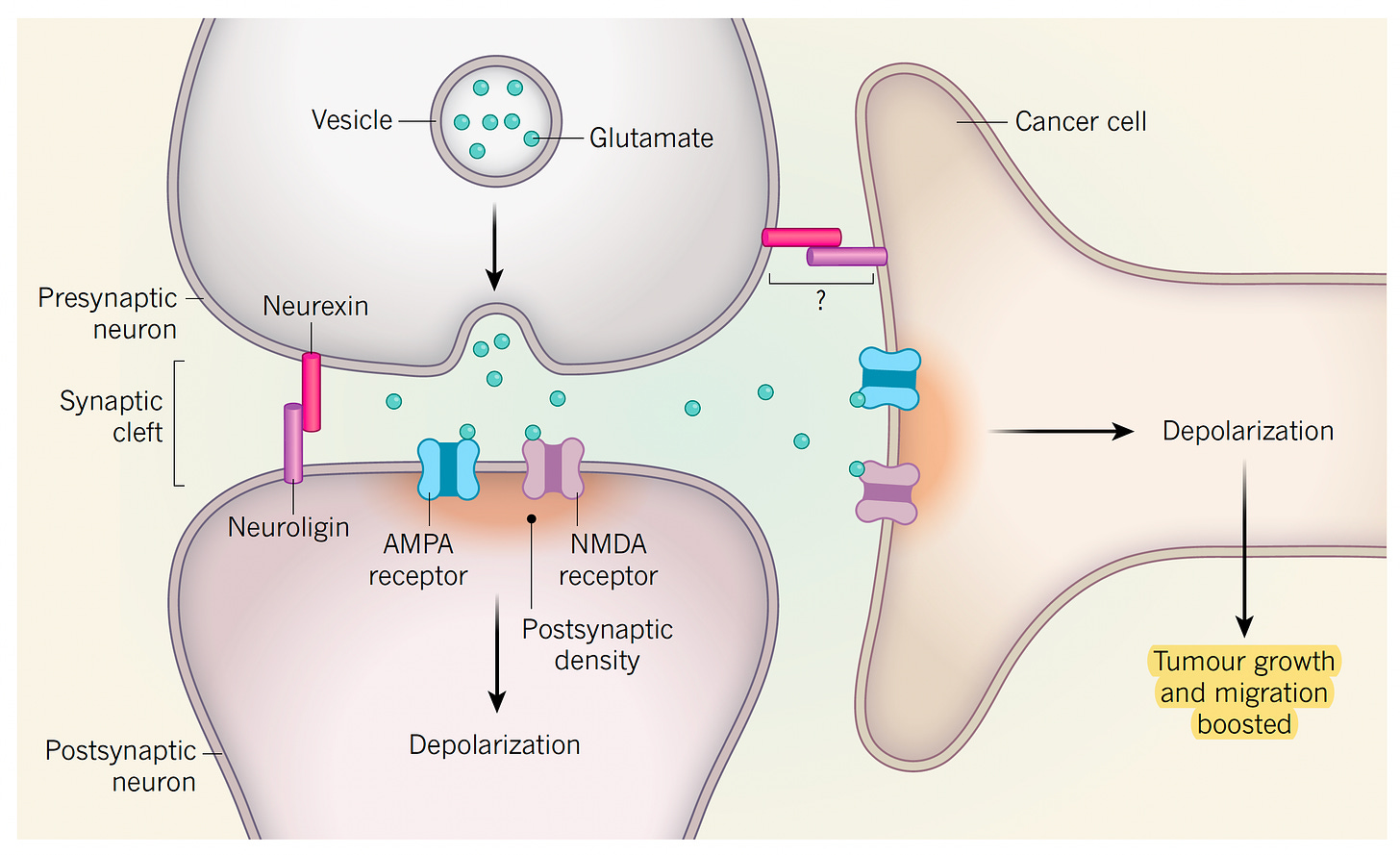

There were multiple publications in 2019 (here, here and here)that established the presence of neurogliomal synapses—the direct connection of neurons with glioma tumor cells, which provided the biologic basis for how tumor growth could be enhanced via this connectivity (as schematically shown below).

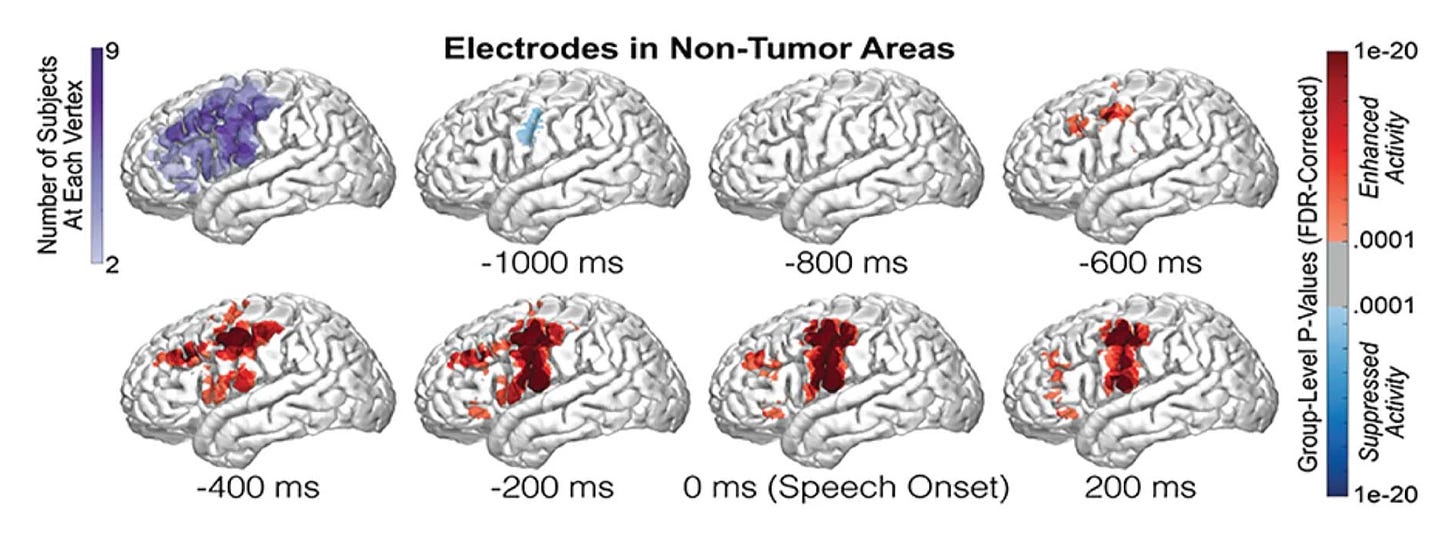

But that seminal work was significantly expanded in the new multi-dimensional study by Prof Shawn Hervey-Jumper and colleagues at UCSF. With the use of intraoperative brain surface electrode monitoring and performance of cognitive tasks in awake patients with gliomas, this work established the mind-tumor connection.

Examples of the simple cognitive testing. See also Panel B (cognitive assessment) in top Figure of this post for other examples.

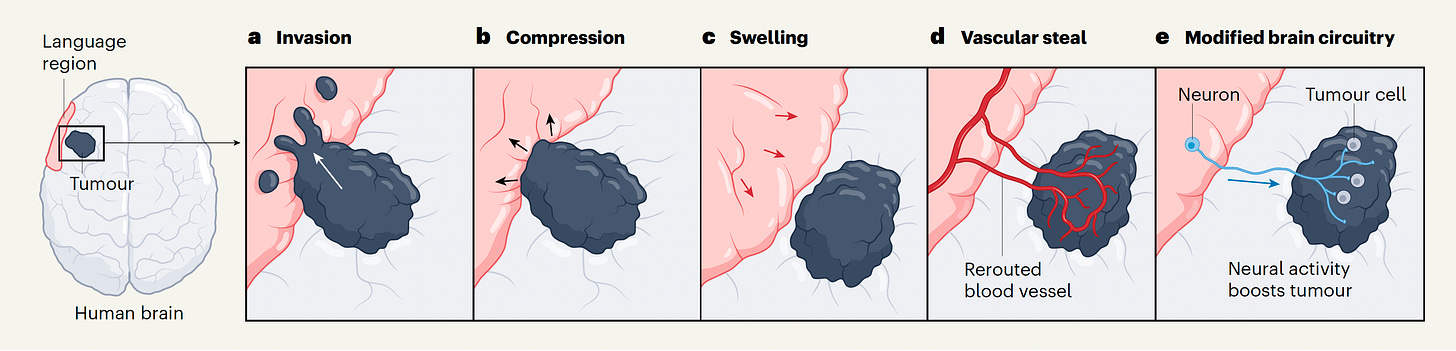

A key finding was that regions of tumor infiltration remote from the language area of the brain had task dependent increased activity (that’s not supposed to happen!), indicating hijacking that had occurred. As Ibrahim and Taylor aptly put it, “The study shows that gliomas attack computational power from the brain by parasitizing neural plasticity, so as to grow at the expense of cognitive function.” This disrupted neuronal circuitry of the brain may in part account for the frequent manifestation of cognitive decline associated with progression of gliomas. Higher functional connectivity, as determined by magnetoencephalography, indicating more tumor-neuronal networking, was associated with more cognitive decline and worse survival. Taking this work considerably further, through 3-D organoid culture, tumor cells and mouse brain, the pivotal role of thrombospondin -1 (TSP-1), a protein participant of synapse formation, was demonstrated along with the potential of blocking this protein to reduce cognitive decline.

This schematic highlights the different mechanisms by which cognition could be affected by a brain tumor, with the new study highlighting the importance of panel e, modified brain circuitry.

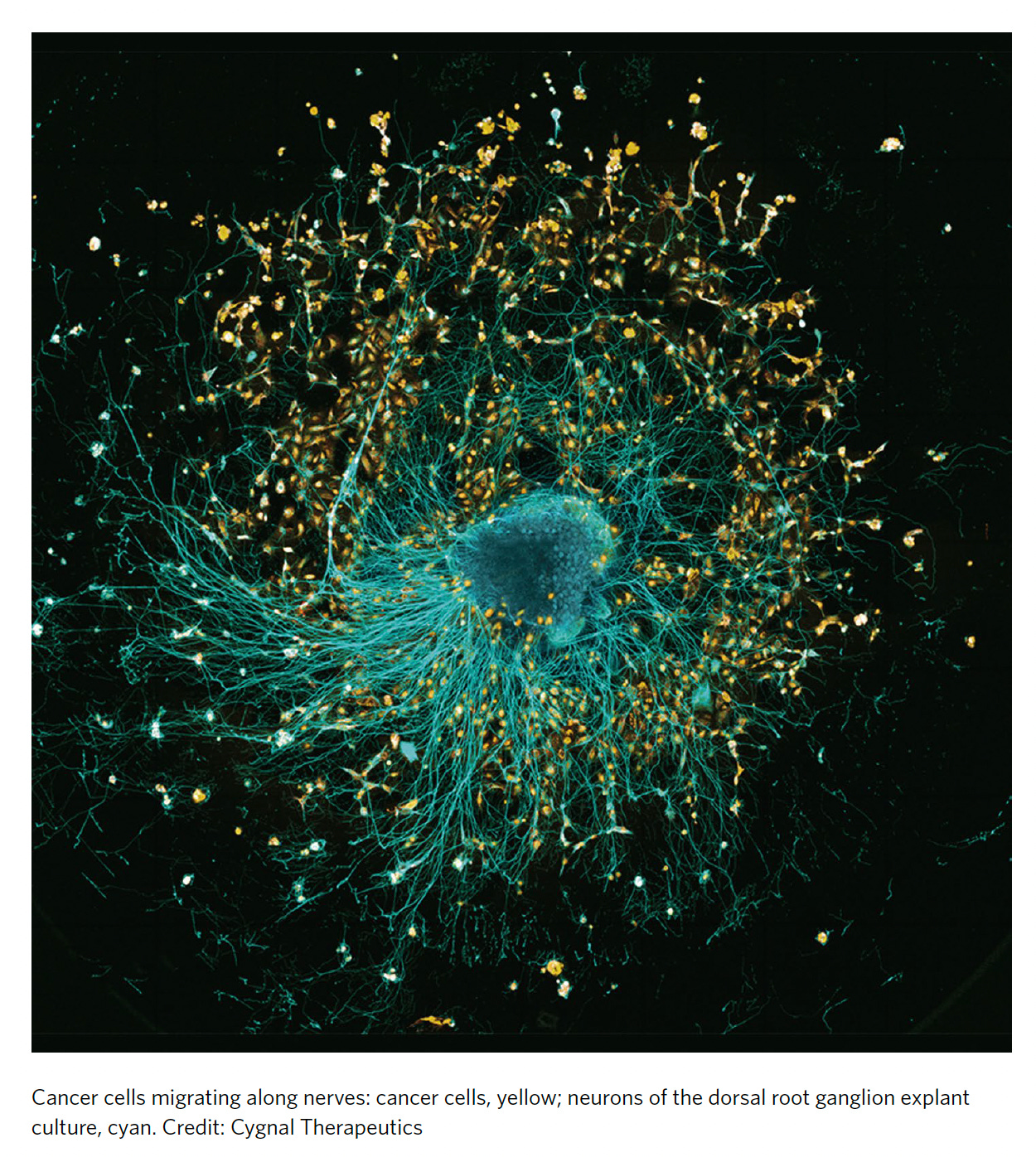

In recent years cancer involvement with neuronal cells has received considerable attention, such as the finding of brain cells in an experimental model of prostate cancer, or the ability of breast cancer metastasis to establish brain neuronal synapses, head and neck cancer, and others. Indeed, a whole new field of “cancer neuroscience” is blossoming with multiple startup companies (the roundup includes the lower Figure below).

But the new study transcends the connection between cancer and neurons, and the potential for tumor growth to be enhanced by such synapses. In patients with gliomas, it has established the bidirectional link between the mind and the tumor. Of course, that doesn’t mean that patients with this brain cancer should stop talking or thinking to reduce tumor spread. But the fact that this crosstalk is happening is stunning, and may well in the future lead to ways to prevent cognitive decline in patients suffering this dreadful type of cancer.

Thank you for reading, subscribing and sharing Ground Truths.

All proceeds from paid subscribers goes to Scripps Research.

I’m excited to announce that the first 2 months of paid subscribers has provided substantial support for many summer interns in our Scripps Research program for high school and college students.