Momentum towards a Covid nasal vaccine is building, thanks to basic science discovery work, results from 2 early clinical trials of different nasal vaccines, and new, major US funding awards to companies to accelerate clinical trials. Before getting into the new details, let me review the rationale.

Rationale and Urgent Need

Back in July 2022, Akiko Iwasaki and I published an editorial in Science Immunology calling for an Operation Nasal Vaccine, to “achieve population-wide respiratory mucosal immunity” to “help us get ahead of the virus and build on the initial success of Covid-19 vaccines.” This piece accompanied a new study in experimental models showing the potential for nasal vaccines to patch up our “leaky” intramuscular vaccines which, after the virus’s evolution to Omicron, have exhibited markedly reduced suppression of infections and transmission. The results of the nasally administered vaccine highlighted that shots don’t provide tissue-level mucosal immunity, but an adenovirus vector nasal vaccine induced marked increases in IgA levels and T-cell immune response in the lung (via bronchoalveolar lavage). Those results were reinforced by many other experimental studies, including Akiko’s group at Yale with the “prime and spike” strategy of a nasal vaccine after 2 mRNA shots that led to strong mucosal immunity (CD8+, CD4+ cells, memory B and T cells, IgA levels), significantly lower viral loads, and less disease and fatality. Another pivotal point is the potential for mucosal immunity to protect against the sarbecovirus family, enabling variant-proof protection, instead of the current approach of coming up with updated booster shots that are unable to keep up with the virus’s persistent evolution (i.e. variant chasing). The virus gets into our body via our upper airway lining (mucosa), so defending this site of entry should, as experimental studies have shown, provide broad protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants. We asserted: “The objective of breaking the chain of transmission at the individual and population level will put us in a far better position to achieve containment of the virus, no less reducing the toll of sickness and long COVID-19.”

There are many skeptics about whether mucosal vaccines (oral or nasal) will be effective and safe, given the track record of multiple failures and the only commercially available one in the United States is FluMist for influenza, which is not highly protective. But Covid is not flu! We pointed out in the editorial that the experience with the influenza virus to date is quite different from SARS-CoV-2 in that Covid shots are markedly more efficacious than flu shots for preventing severe disease (and up to 95% efficacy vs infections prior to Omicron), and the difference between Paxlovid vs Tamiflu for efficacy is striking. We’ve triumphed over SARS-CoV-2 far better than influenza with vaccines and therapeutics because in many ways it’s an easier target. There’s good reason to be optimistic.

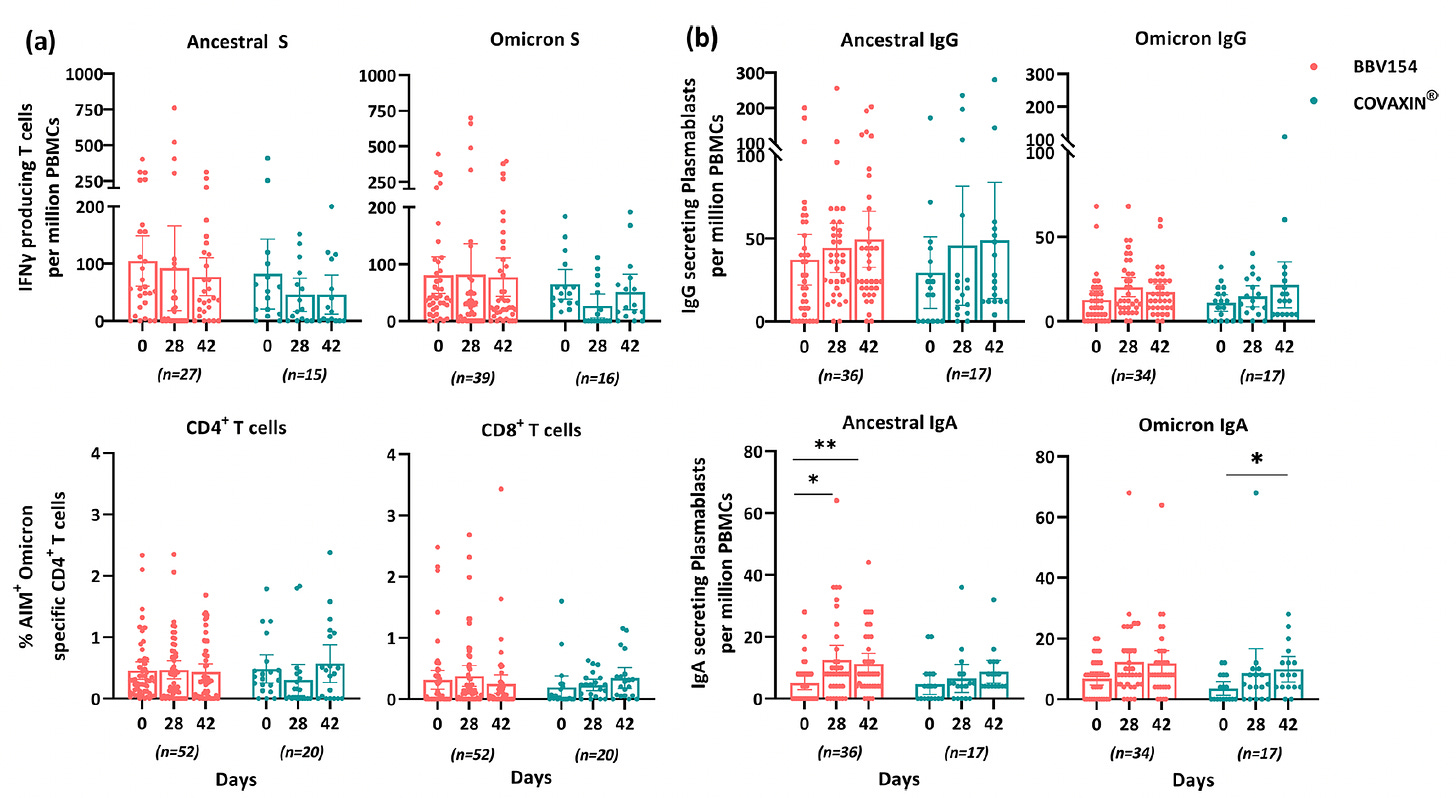

Leading steps of progress in recent weeks was the August 2023 publication of the Bharat Biotech nasal vaccine, commercially approved in India since early 2023 (intellectual property licensed from Diamond lab, Washington University, USA). In the randomized trial comparing the nasal vaccine (BBV154) vs shots (Covaxin), there was higher magnitude and extended duration of mucosal immunity induced.

Even Moderna, which had shown no signs of developing a nasal vaccine, published a 22 September paper in Science Advances with evidence that it worked well, in the hamster model, with “decreased viral loads in the respiratory tract, reduced lung pathology, and prevented weight loss after SARS-CoV-2 challenge.”

Writing in Science this week, Florian Krammer and Ali Ellebedy reviewed the landscape about variants and what’s needed to combat future SARS-CoV-2 variants. They concluded: “Similar broadly protective vaccines, potentially given mucosally (e.g., intranasally), are urgently needed for SARS-CoV-2. These vaccines will provide a much-needed advantage in the ongoing struggle against this virus’s rapid evolution.”

Recent Completed Phase 1 Studies

There are more than 20 nasal Covid vaccines in development, but two companies recently announced their Phase 1 human trial results and have received new US government support.

In July, Castlevax, a spinout from Mount Sinai in New York City (Florian Krammer is on the Advisory Board) released the results of their Phase 1 trial, which tested 2 intranasal doses of their live recombinant vaccine (NDV-HXP-S) using a Newcastle Disease (a para-myxo virus-induced disease in chickens with asymptomatic or only mild, self-limiting impact in humans) vector expressing the SARS-CoV-2 spike in participants who had received prior mRNA shots. Importantly, it uses a 6-proline substitution in the spike instead of the 2-proline that has been incorporated in most commercial Covid vaccine shots (schematic below), the significance of which I will review later (vida infra). Actual data are not yet available but the company’s press release indicates a robust secretory IgA response, which goes along with achieving some degree of mucosal immunity. Previously, in February, Krammer and colleagues published their data for this NDV-HXP-S vaccine for inducing a higher proportion of neutralizing receptor binding domain (RBD) antibodies than mRNA shots.

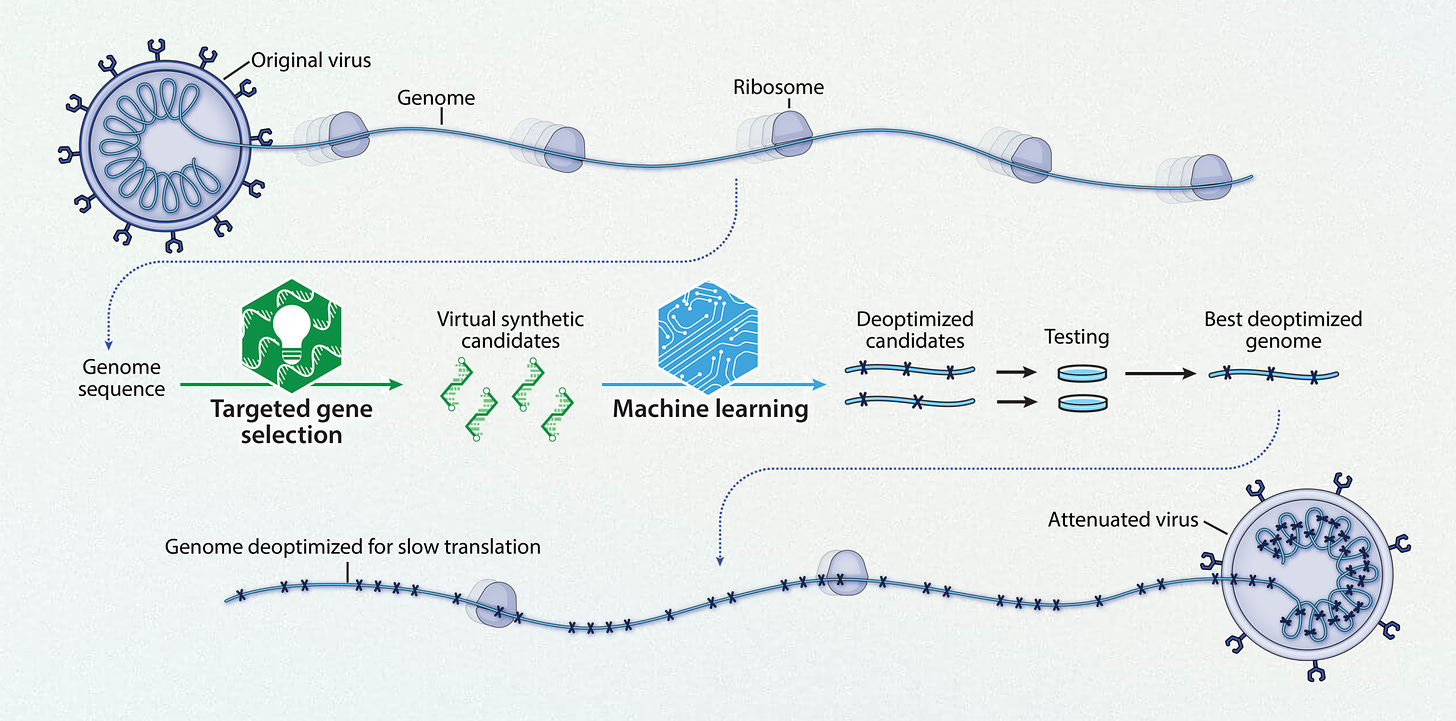

This week Codagenix presented their Phase 1 nasal vaccine (“CoviLiv”) data at the Infectious Disease Society meeting in Boston. This vaccine is a spinout of Stony Brook University, intellectual property from Eckard Wimmer. Using a live-attenuated intranasal vaccine (derived through machine learning as schematically shown below), in a randomized, double-blind, a dose-escalation study (in participants who had not received prior mRNA vaccination) “robust humoral and cellular responses” was induced, with T-cell reactivity to multiple proteins of the virus besides the spike, mimicking natural infection.

The actual results were presented by the investigators at the meeting, summarized as follows: “After 2 doses of CoviLiv, all participants exceeded a 2-fold increase in spike-specific IgG with a geometric mean fold rise of 19.5 (95% CI 3.4-113.8) on day 57. Neutralizing antibodies at this timepoint were induced 2.6-fold (CI 1.0-7.0) and 4.9-fold (CI 1.4-16.6). On day 36 post-vaccination, IFNγ response increased 4.5-fold (CI 2.8-7.4) in the 2-dose cohort and 2.5-fold (CI 1.4-4.2) in the 1-dose cohort.”

Of note, this vaccine is being assessed in an ongoing large Phase 3 trial with the World Health Organization SOLIDARITY multicenter (multinational) clinical trial unit that conducted multiple randomized trials during the pandemic.

Project NextGen Kicks In

The United States government announced Project NextGen in April and subsequently published its objectives in NEJM in August: “This $5 billion investment will focus on three main areas: vaccines that provide broader immunity both against new SARS-CoV-2 variants and across the family of epidemic-prone sarbecoviruses, vaccines that generate effective mucosal immunity to block infection and transmission, and monoclonal antibodies that can weather viral evolution and serve as a basis for our arsenal against new threats from betacoronaviruses.”

On October 13th, the HHS announced funding for Codagenix and Castlevax, initially for $10 million and $8.5 million respectively, but after achieving milestones up to $389 million each. The goal of funding is to accelerate clinical development for large trials of 10,000 participants—as soon as possible—who had mRNA shots and receive these nasal vaccines as a booster. Due to lack of Congressional support, it took a long time to establish Project NextGen, and once formed time to select the programs/companies with best prospects for acceleration of nasal vaccines. Finally, we’re seeing it happen and it’s certainly good news. And whatever comes from the investments will very likely be helpful for future pandemics.

A Triple Intranasal Vaccine Against Measles, Mumps, and Covid

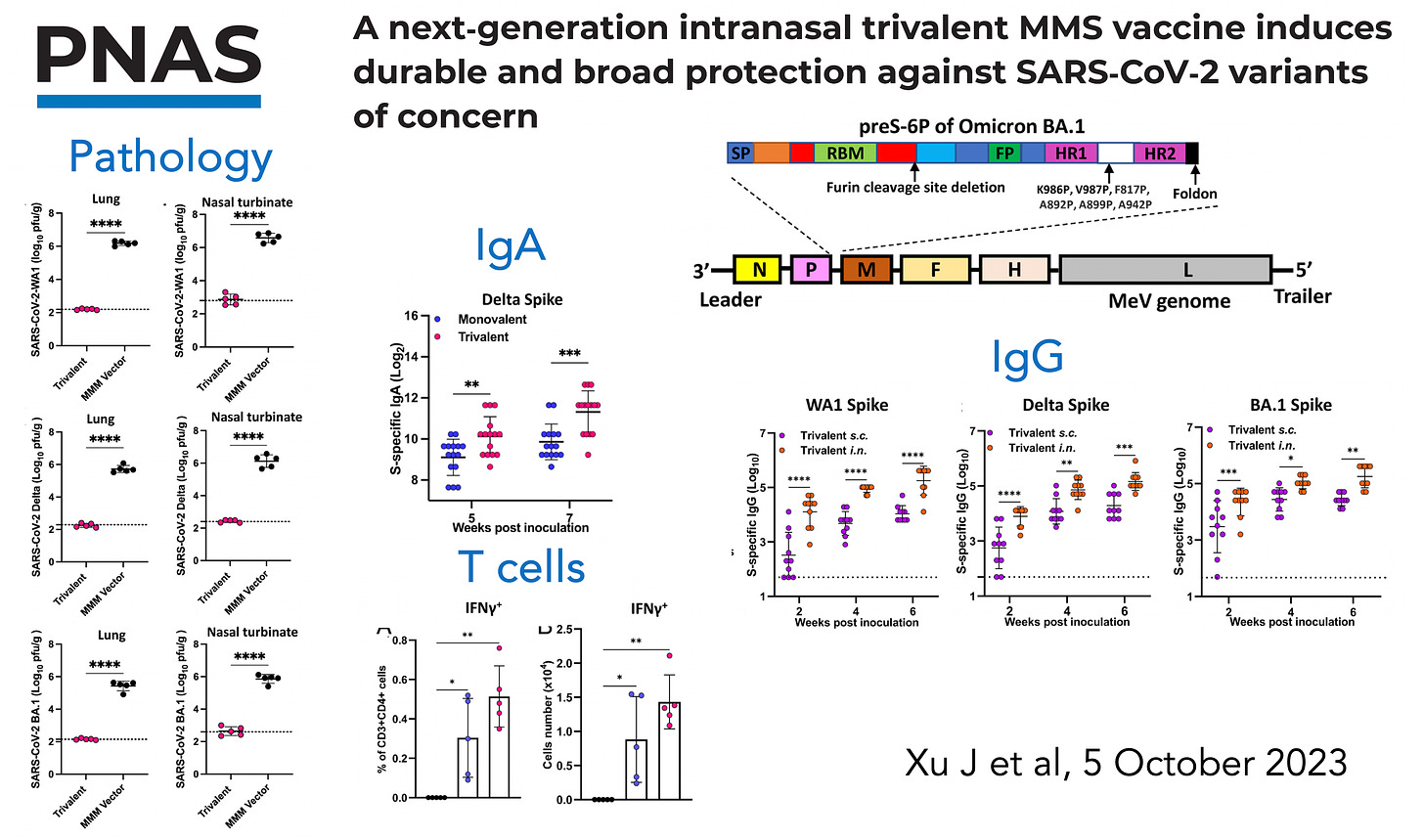

Earlier this month, researchers at Ohio State published an impressive study taking the MMR vaccine (measles, mumps, and rubella) that has been safe and effective for >50 years, and with that as a foundation constructed a MMS vaccine (mumps, measles, SARS-CoV-2) given intranasally, with the use of the 6-proline substitution to stabilize the prefusion spike protein. The graphic below summarizes the findings in 2 different animal models for pathology, mucosal immunity reflected by IgA induced, effect on T cells (interferon assay, among many others) and IgG antibodies to multiple variants (Wuhan, Delta, and Omicron).

The potent immune response for this nasal vaccine was likely facilitated by the 6-proline substitution. The 2-proline substitution (top of diagram below), from discovery work by Jason McLellan, Barney Graham, and Andrew Ward, was incorporated in nearly all of the Covid vaccines (Pfizer, Moderna, J&J, and others) because it stabilized the spike protein, so that once it entered the cell, a far greater immune response was elicited. Subsequently, Jason McLellan and colleagues have published marked improvement for a 6-proline substitution (HexaPro) (bottom of graphic below). Multiple other reports have confirmed a much stronger immune response and protection, such as 70% lung protection with HexaPro vs 20% with the 2-proline substitution across different variants in the experimental Covid model.

Much of the above was captured in my conversation with Ira Flatow this week on Science Friday. If you have a chance to listen to the podcast (transcript not yet available) you’ll be in touch with the excitement about these new developments.

Summary

While there is no major wave of Covid infections at the moment, the number of people who are still getting infected or reinfected each day is substantial. We have no good way to prevent these infections besides non-pharmacological interventions (masks, physical distancing, air ventilation and filtration, etc). Shots provide only moderate (30-40% reduction) and brief (<6-8 weeks) protection from infections. Pandemic fatigue is full blown; the world is doing all possible to move on even though the virus forges ahead on its evolutionary arc, destined to find new ways to infect (and mostly reinfect) more hosts. There are known variants, currently at low levels, that will be more problematic than what we are seeing right now (such as the FLips, recently reviewed) with a new wave likely to be seen in November. Despite our progress with updated XBB.1.5 monovalent vaccines and Paxlovid availability, these infections carry a risk, some of which is unpredictable, for severe Covid and Long Covid.

The big gap in our armamentarium is an easy to administer, durable, potent, variant-proof, safe nasal vaccine that blocks infections and transmission. Even if it was necessary to take it every 3 or 4 months, the protection it would provide would help our exit ramp from Covid concerns, further moving us back towards pre-pandemic life.

We’re not there yet, but there have been many recent and important steps forward. The 6-P (proline) substitution would have ideally been incorporated into our Covid shots some time ago, but this basic science advance may wind up as a way to get nasal vaccines onto a successful path. Getting funding support from the government has been frustrating, to say the least, but it is finally off the ground. While it may not be the Operation Nasal Vaccine that we asked for, the financial support and milestone incentives will definitely help accelerate the requisite clinical trials.

A frequent question that I get asked: “When may we see a Covid nasal vaccine in the United States?” Maybe never. But I think there’s increasing likelihood that it may happen before the end of 2024. Yes, that’s too long a wait given its “urgent need” and the promising results emanating from so many US academic labs over the past couple of years. But remember Covid will be with us for many years to come, so a highly effective and safe nasal vaccine will be most welcome whenever it’s ready.

Thanks for reading and subscribing to Ground Truths!

Please share if you found it helpful.

All proceeds from Ground Truths go to Scripps Research.

A nasal vaccine by the end of 2024 may be too long in many ways, but to me it sounds like relief really may be here in my lifetime, which I don’t take lightly. There have been many days where I have assumed that I would never do many things again because it wouldn’t be safe. Any hope is welcome.

A great review thank you. The skeptic in me was relieved to read this line:

“Even if it was necessary to take it every 3 or 4 months”

Given the very short incubation time, this virus will never be eradicated with vaccination like other, slower viruses like polio, smallpox, etc.

I’ll hope for good outcomes data, without major safety concerns, and gladly get a spray 2-3 times a year if needed!