The Hospital-at-Home movement

The pandemic gave it a jolt and it's just getting started

In 1946, George Orwell wrote in How the Poor Die that the hospital is a sort of “antechamber to the tomb.” While we have been well aware of the escalating costs of hospitalization, along with nosocomial infections (acquired in hospital), the unnecessary procedures performed, and the medical errors that are frequently made, it took the pandemic to awaken the fledgling hospital-at-home strategy in the United States.

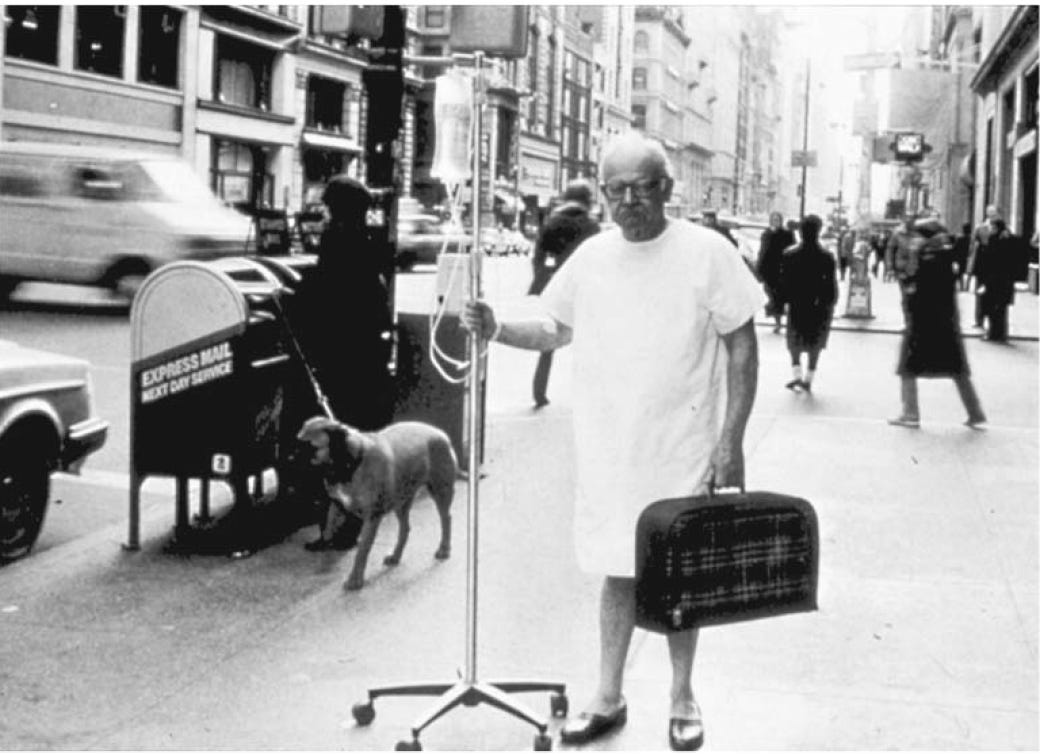

Back in 1988, as we were getting accustomed to myocardial reperfusion therapy, I led a small randomized trial of early hospital discharge 3-days after an uncomplicated heart attack, as compared with the conventional 7 to 10 days. Not only did this save an average of over $5,000 (in 1987 dollars), but also led to earlier return to work. At the time such a short stay in the hospital was unthinkable, and advertisements like the one below (which I found especially humorous) poked fun at the concept.

Over the years since there has been a marked reduction of length of stay for heart attack, with the average in some countries, such as Norway, down to 3 days. It’s about 5 days in the US now, an average of all types (complicated and uncomplicated) heart attacks. We’ve learned time and time again in in medical practice that it takes a long time to see change. After reading this essay, my friend Chris Handel sent me this 1896 JAMA article quote: “It is a remarkable and lamentable fact that many years often elapse before an important and scientifically established discovery in either the theory or practice of medicine becomes an essential constituent of diagnosis and treatment in the hands of the practicing physician."

In The Patient Will See You Now book that was published in 2015, I had a chapter entitled “The Edifice Complex” and wrote :”Hospitals, as we know them today, will eventually become extinct.” As I see it, in the years ahead, patients not requiring an intensive care unit or emergency room assessment, will be more safely and inexpensively cared for in the comfort of their own home.

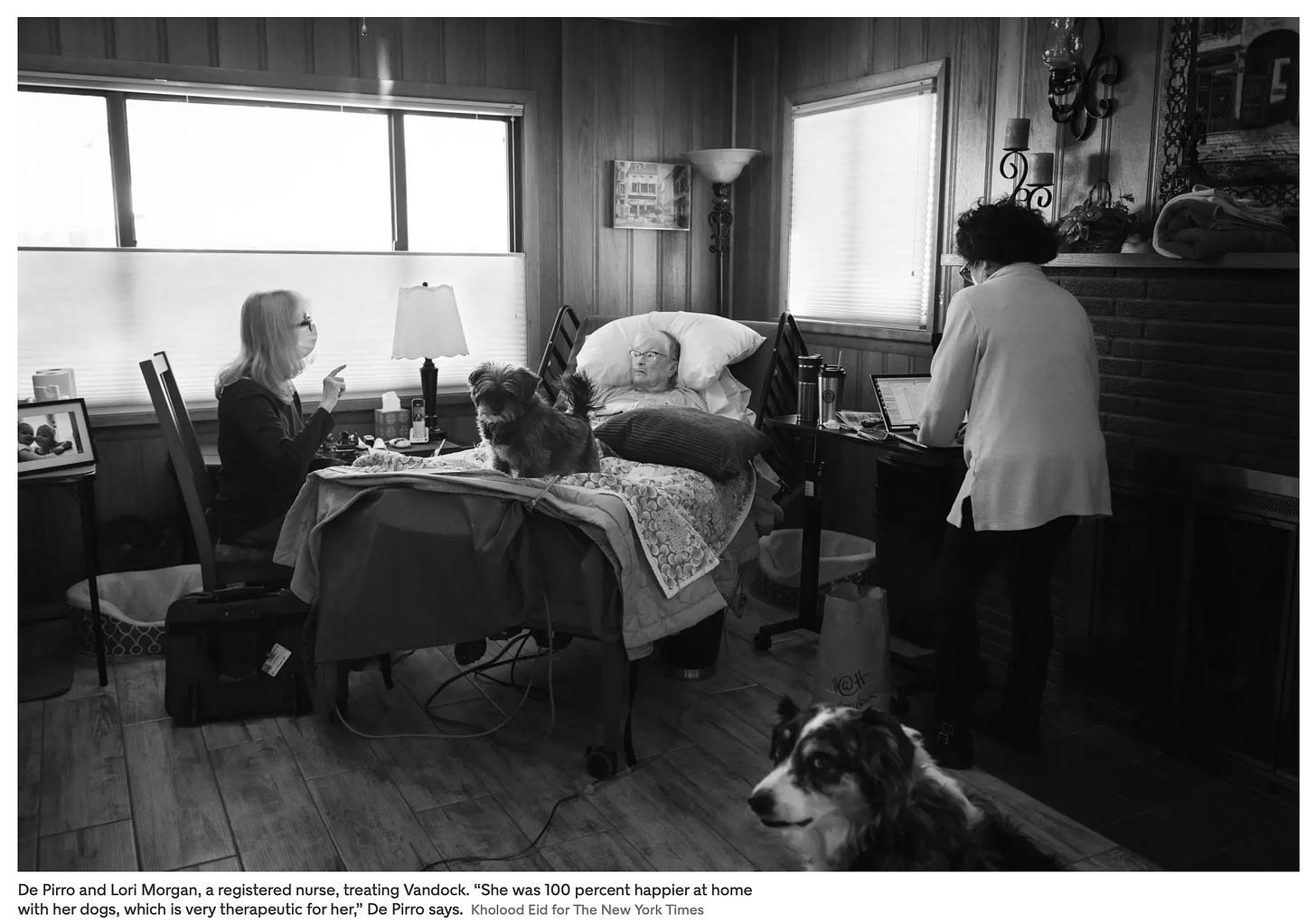

A couple of weeks ago, Dr. Helen Ouyang, one of the most talented American physician-writers, had a feature in the New York Times Magazine “Your Next Hospital Bed Might Be at Home.” She reviewed some of the important history. In 2005, Dr. Bruce Leff of Johns Hopkins authored a paper in Annals of Internal Medicine prospectively showing feasibility and safety of hospital-at-home in 3 health systems, with lower costs and some evidence of fewer complications. The patients were age 65+ and the diagnoses were restricted to heart failure, chronic obstructive lung disease, pneumonia or skin infections (cellulitis). As an outgrowth of this report, a few years later in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the Presbyterian Healthcare at Home program, one of the first in the United States, got started. Many of the photos from Dr. Ouyang’s piece were of patients in this program, also showing Dr. Elizabeth De Pirro in the lower photo below, who conducts rounds of the patients in their homes, often driving 100 miles a day around the city.

Over the course of the past 15 years, the Presbyterian program has cared for less than 1,600 patients. In lieu of the hospital, hundreds of patients were treated at home in the Mount Sinai program in New York City, led by Drs. Albert Siu and Linda DeCherrie, also nicely showing feasibility and safety, supported by CMS (a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services innovation grant). The 8-year-old program at Faulkner Hospital (of Brigham Hospital in Massachusetts) provided care for 600 patients at home in 2021. The Hospital at Home Users Group, a US and Canada collaboration, organized by Drs. Leff, Siu, DeCherrie and Levine, lends guidance for developing HaH programs. But before the pandemic, the programs mentioned here were about the limit of scale—small.

The Pandemic Opens the Floodgate

After many years of incubation, telemedicine only blossomed during the pandemic out of necessity. With the need for physical distancing, telehealth visits went up exponentially. Besides fulfilling the patient-clinician ability to meet virtually, there was one major factor that changed: the visits were reimbursed by Medicare and private insurers.

The same phenomenon occurred in November 2020 with CMS—the ability for health systems to get a waiver such that patients treated at home would be reimbursed at the same level as in-hospital. Prior to this waiver, CMS required 24/7 presence of a registered nurse for parity in reimbursement, which obviously greatly constrained its use—now that is waived. Quickly >5% of US hospitals, >250 health systems (many with multiple hospitals) in 37 states, have obtained a waiver. As a result, many companies to facilitate HaH for health systems have gotten legs, including Medically Home which notably has worked with Kaiser Permanente since the pandemic began to help them treat over 2,000 patients at home. That’s with Medically home based in Boston providing remote nurse virtual video connects to Kaiser’s home patients on the West coast (CA, WA, OR). That’s very different from the Presbyterian program model which is all in-person. As I’ve emphasized in Deep Medicine and other writings, the importance of human touch cannot be over-emphasized, such that programs that can integrate in-person clinician visits may have a higher likelihood of success.

The waiver led to an explosion of interest in HaH, but it’s unclear whether it will be continued. On the other hand, what has become clear from this experience is that just obtaining the waiver is quite different than launching a successful HaH program at scale.

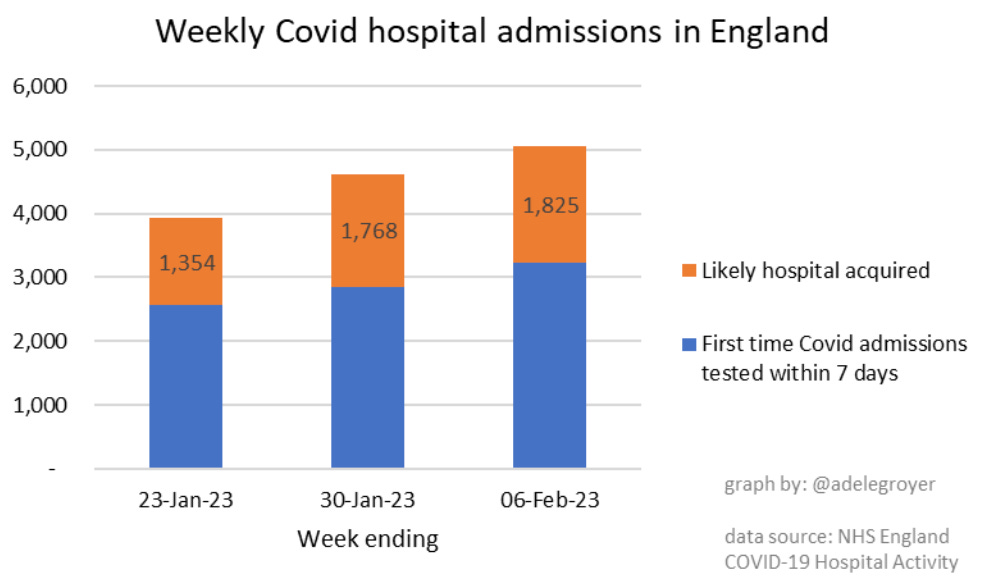

One other important thing the pandemic brought to light: the high number of Covid hospitalizations that are attributable to nosocomial (in-hospital acquired) infections, as shown in a recent slide of NHS England data posted by Adele Groyer. This has also been borne out in many countries that are carefully tracking nosocomial Covid. At times, up to half of Covid hospitalizations were nosocomial.

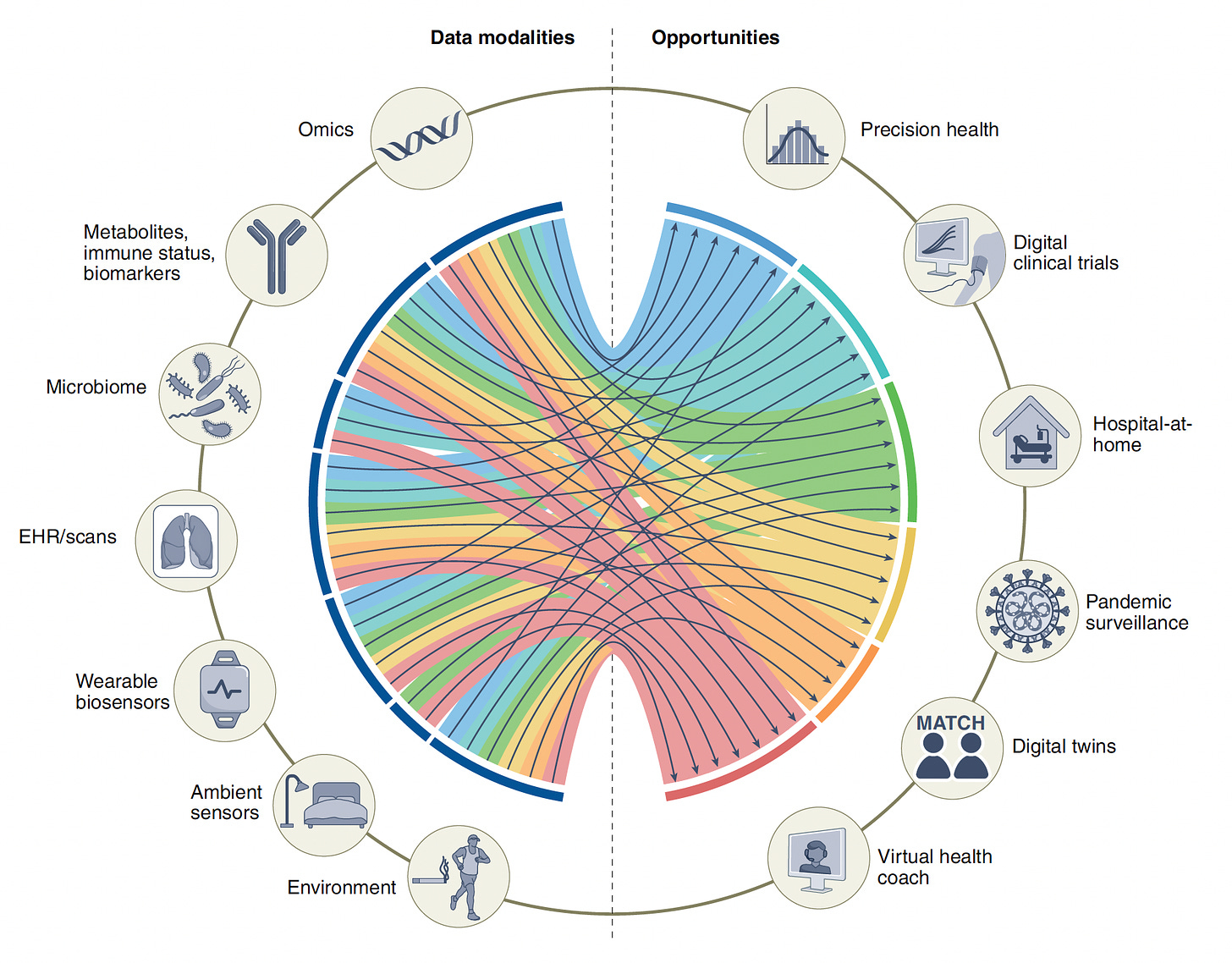

Hospital-at-Home 2.0

Besides the need for investment to launch and operate an HaH program, they are now void of any deep data about the patient. Whether it’s an at-home set of vital signs or a wearable sensor patch (the Ouyang NYT Mag piece brought out the technical difficulties with Biofourmis’s patch and connectivity), it’s still the tip of the iceberg of what data can now be captured and integrated to help understand a patient’s status—in real time and, if need be, continuously. Bringing all the data modalities together for analytics involves multimodal AI, which I recently reviewed with my colleagues in Nature Medicine. The Figure below from that review shows the opportunity for HaH, and other use cases, going forward. The ability to integrate such data has been a limiting issue, but large language models (LLMs) that can deal with over a trillion parameters, including the interface between text, speech and images, are well suited to actualize this capability. I recently reviewed these LLMs or foundation models, the exemplar ChatGPT is certainly the craze right now. While there’s been much interest in sensors that collect physiologic data, the progress in wearable patches for self-ultrasound imaging is also notable. Let me emphasize that for HaH and any other use cases in the Figure below, this—multimodal AI—has not been done yet. It’s an aspiration which may be accelerated with LLMs but the case hasn’t been cracked yet.

This is similar to telemedicine visits, which are for the most part simply a video chat now. As we’ve written, telemedicine 2.0 will evolve to be an active data exchange between the patient and clinician. The same holds for HaH’s future, although at a much deeper and richer scale.

The dynamics in the financial space demonstrates keen interest. Venture capital is backing HaH technology companies such as Biofourmis which already has a $1.3 billion valuation. Best Buy acquired Current Health for $400 million, a sensor used to monitor patients with moderate Covid at home. Allina Health, a Minneapolis based health system, invested $20 million in Inbound, an HaH company. The acquisition of Signify Health by CVS health and AMC Health partnership with GE Healthcare further show interest for large companies to have a home presence for remote monitoring.

Where Do We Go From Here?

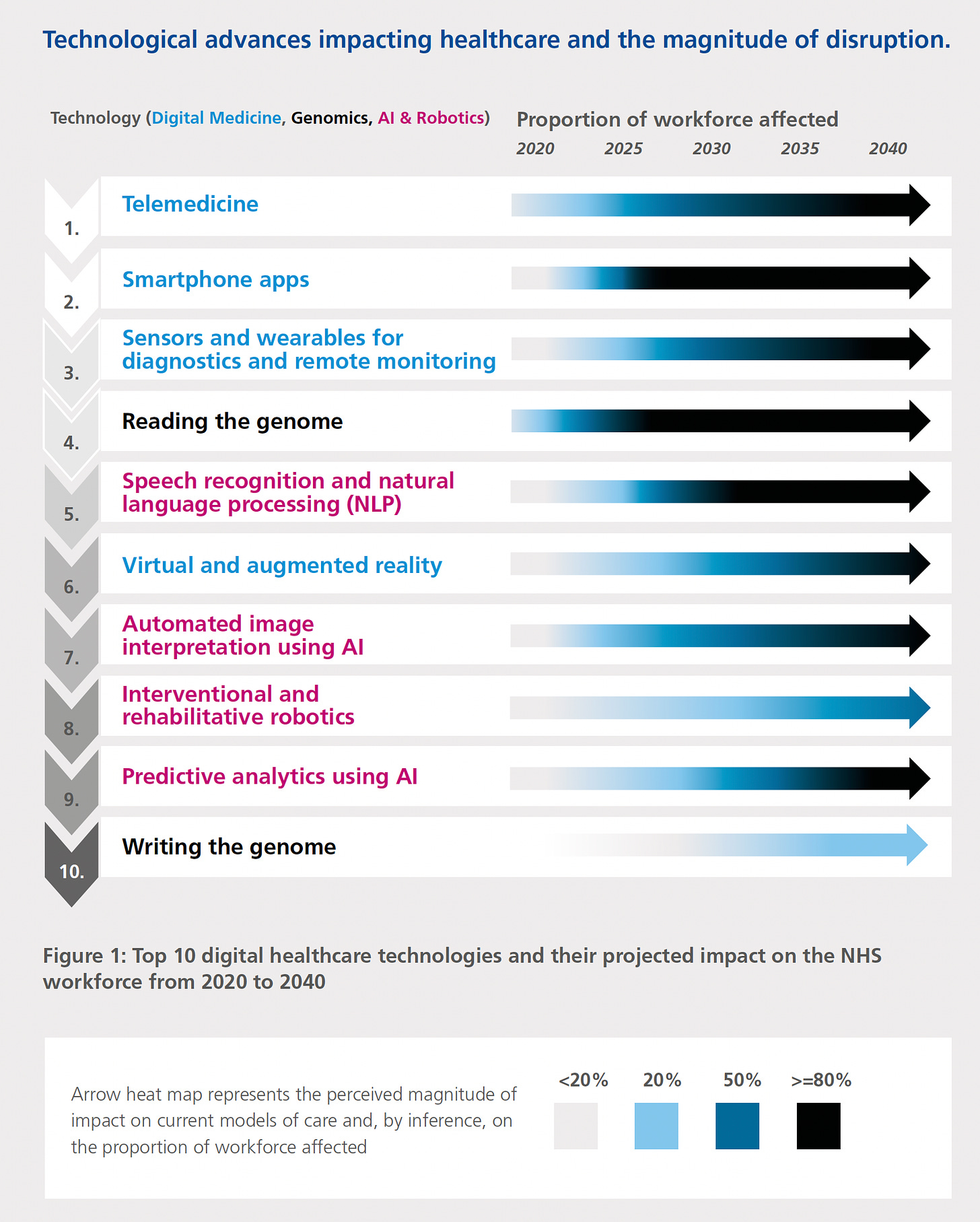

The United States is poorly positioned to be a leader for HaH. More than a third of the $4.3 trillion health expenditures in 2021 went to hospitals and the American Hospital Association (AHA) is one of the country’s (5th) leading lobbying groups for the government. To put it mildly, the AHA has zero interest in HaH’s success. Unless there is a dramatic change in reimbursement, such as has been incentivized short-term by the CMS pandemic waiver, there is no financial reason why health systems will make up front investments to pursue HaH. We have already seen other countries take the lead in HaH, such as Australia, Canada, and several in Europe. Places with universal health care (i.e. all industrialized nations except the United States) are better suited, such as the UK. Researchers in Osaka, Japan published a preprint of hospital-at-home during the pandemic. When I did the review of the UK National Health Service for use of AI and digital technologies in 2019, with a gifted inter-disciplinary team, we identified remote patient monitoring, with hospital-at-home, to be the most transformative potential technology in the next 2 decades. The graph below shows our consensus ranking of the different technologies on the horizon.

The Need for Compelling Evidence

A meta-analysis of 61 small randomized HaH (vs hospitalization trials showed a 19% reduction of mortality, 25% lower readmission rates, and significant reductions in cost. Patient satisfaction was higher in 21 of the 22 studies for which it was tallied. These trials were conducted without sensor technology or AI analytics, which have the potential to further increase safety. That, in itself, remains an unanswered question. That’s an excellent body of evidence to start with, but it’s not enough.

In order to take hold once and for all, there needs to be larger scale, multicenter randomized trials of HaH vs hospitalization to demonstrate safety, lower cost, and patient preference. There are obvious choices as to a narrow set of diagnoses, like Leff used in 2005, or a much broader, all-comer approach. Different diagnoses and patients may require different data tracking systems. When asked to participate, many sick patients will understandably not be comfortable without being in a hospital, which will introduce a bias of ascertainment and a constraint for extrapolating the results.

A critical component will be to develop multimodal algorithms that track a patient well enough to predict an accurate trend of potential decompensation, with enough time in advance such that an intervention can be deployed remotely or a clinician team will be dispatched and arrive at the patient’s home. Even before such a pilot or full scale trial can be launched, we need to address the liability issues that Simon and colleagues have aptly highlighted. There is concern about exacerbating inequities in care, but it was good to see the New York City report that HaH worked well for economically disadvantaged patients. If you have an Apple Watch and like me received an alert that you have fallen, and ask whether 911 be called, you know full well—when you haven’t fallen— the unnecessary stress such errors induce. Accuracy is obviously paramount. We know there are biases and limitations of current biosensors, such as inaccuracy of oximetry for dark skinned individuals. The general concerns of AI including embedded biases, explainability, privacy and security, all fully apply here. At the same time, we should keep in mind that the hospital “gold standard” for safety does not deserve its benchmark status, such that the bar for proof of non-inferiority or superiority is not expected to be so high or formidable.

HaH has profound promise for how we render healthcare in the future. It could ultimately be even bigger than the major movement from in-patient to out-patient for procedures. It will require that some clinicians become “home-ists” rather than hospitalists and a very substantial reconfiguration of the use of current facilities, things that are major challenges to the typical sclerotic health system. But if we’re interested in leveraging current technology and analytics, reducing costs, and providing the best care and comfort for our patients, we should be prioritizing HaH research now to pave the way.