Now into the third year of the Covid pandemic, it’s beyond disheartening. But there’s another way to look at it that’s far more upbeat, not losing sight of good fortune, invoking the Pollyanna principle: the tendency for people to remember pleasant items more accurately than unpleasant ones.

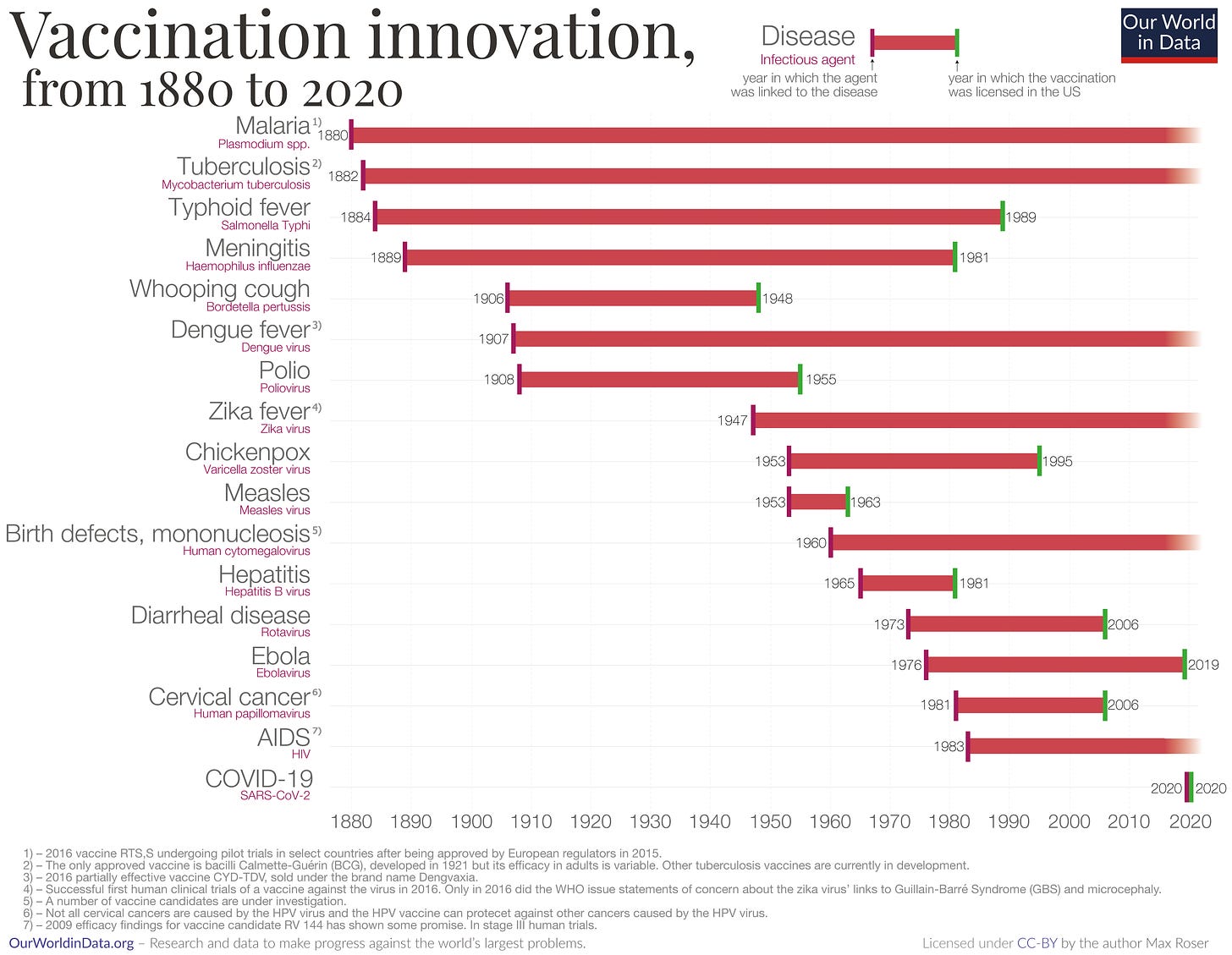

That it took 10 months from having the sequence of SARS-CoV-2 to development of mRNA vaccines and completion of large scale trials with over 70,000 participants —no less with 95% efficacy against symptomatic infections—is historic. For reference, from 1880 to present, the average time it has taken to develop a successful vaccine is nearly 10 years. That’s a best case scenario since for many pathogens, like HIV, we still don’t have a vaccine after many decades. The 95% mRNA vaccine efficacy is a veritable standout as very few vaccines have achieved such a high level.

We’ll never know precisely how many hundreds of thousands of deaths and perhaps millions of hospitalizations that have been prevented by vaccines, but many modeling reports have suggested that to be sizeable.

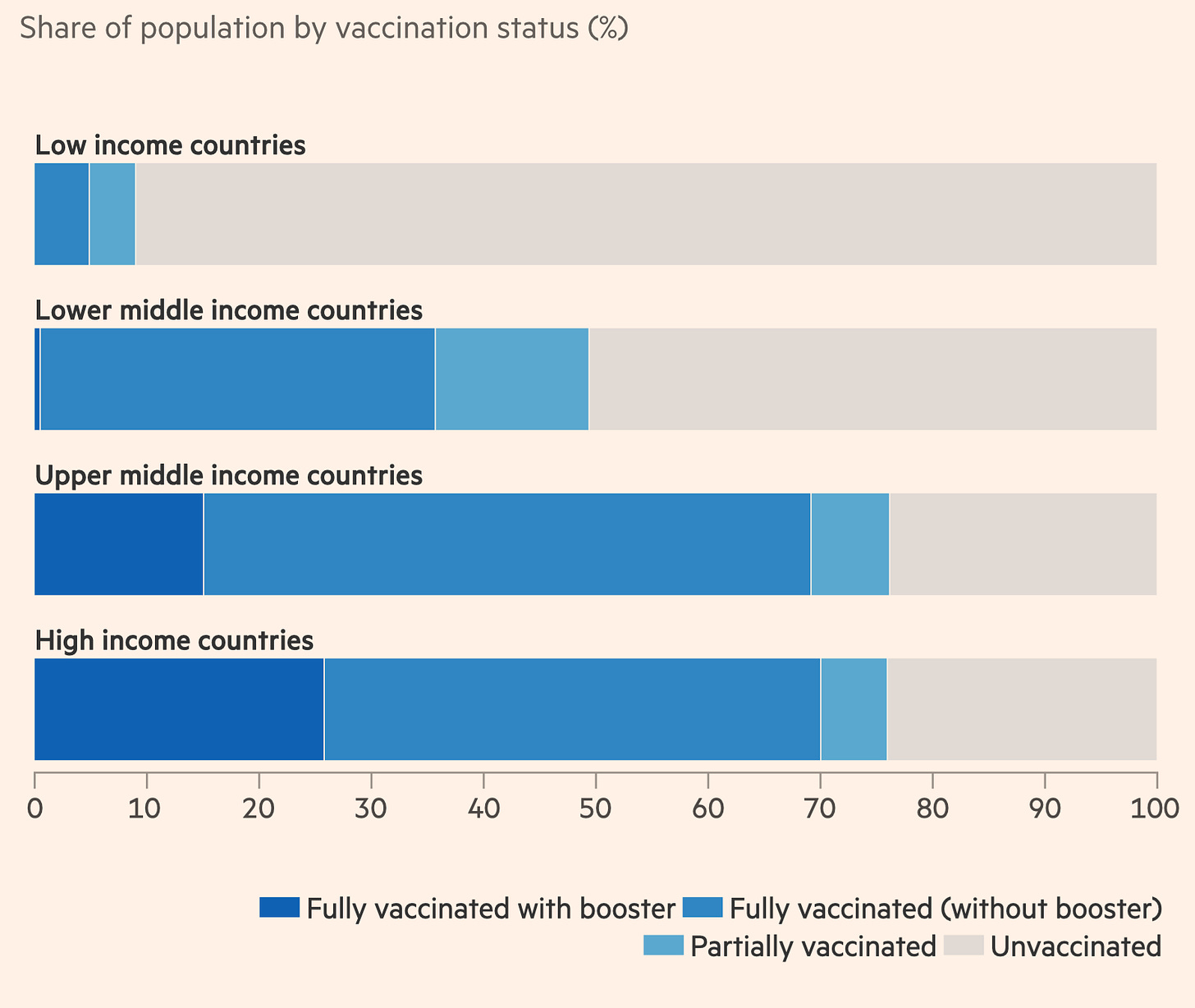

Already, there’s been more than 9.4 billion doses of vaccines administered throughout the world with remarkable safety, yet quite unevenly distributed among 7.9 billion people. Yes, the “lucky” qualifier applies only to upper and upper middle income countries. Hopefully we’ll see far improved production and distribution in 2022 to achieve the global vaccine equity that must occur to achieve containment and endemicity.

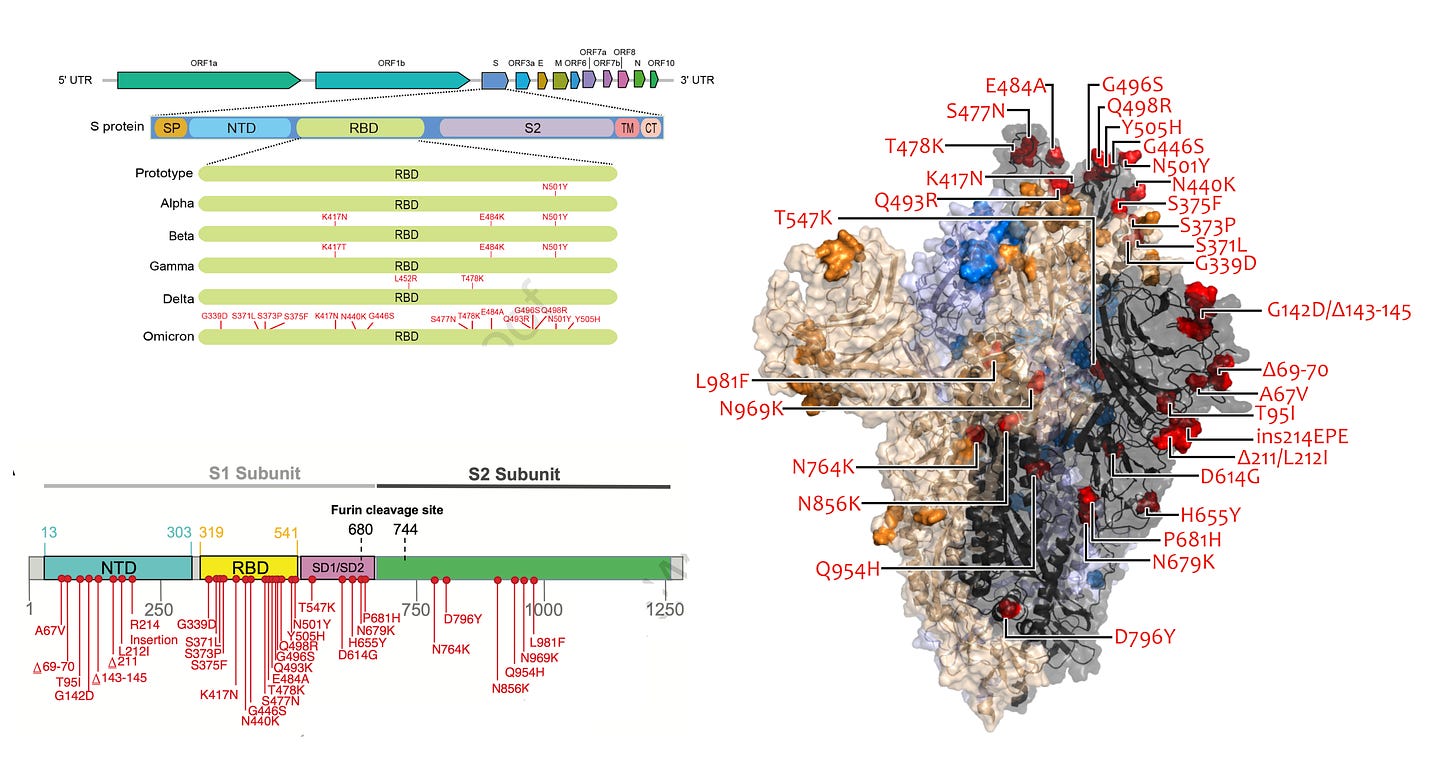

But to continue with the lucky streak, the original vaccines were targeted to the Wuhan ancestral strain’s spike protein from 2019. The spike protein, no less the rest of the original SARS-CoV-2 structure, is almost unrecognizable now in the form of the Omicron strain (see antigenic drift from prior post). While there’s naturally been much focus on the extraordinary number of mutations in the receptor binding domain and the rest of the spike protein, over 50 mutations are spread out throughout Omicron, making the prior major variants of concern (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta) lightweights with respect to changes in structure that are not just linear or uni-dimensional. Each mutation can interact with others (epistasis); any mutation or combination of mutations has the potential to change the 3D structure of the virus. In this sense, Omicron is an overwhelming reboot of the ancestral strain.

So why are we “lucky” with respect to Omicron? Clearly the immunity wall that has been built by vaccinations, boosters, and prior infections has lessened the hit. That does not appear to be playing out nearly as well in the United States as it has in Denmark, Ireland, Norway, Israel, and the United Kingdom to date because vaccination and booster rates are much lower. Beyond the immunity wall, there is now abundant evidence from both clinical and experimental studies that Omicron infections are less severe. That does not mean this strain is incapable of killing or inducing severe disease. It can and does. But the aggregate evidence so far suggests the immunity wall and intrinsic properties of the virus are associated with about 50-70% less severe disease. With all the mutations, it certainly would have been possible for Omicron to be more virulent and induce more severe disease.

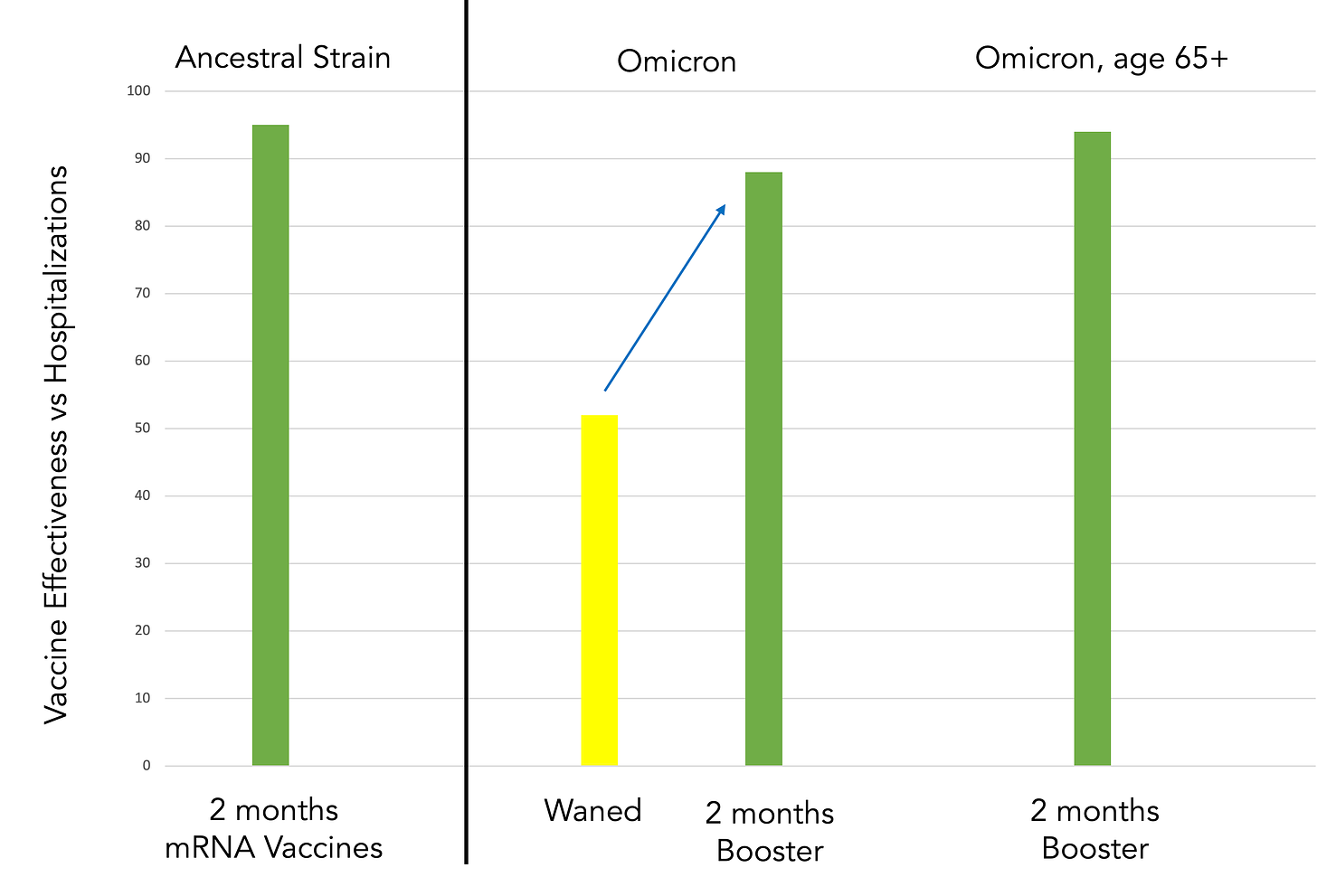

It’s not just the fastest development of highly effective and safe vaccines, not just the less severity of the hyper-mutated Omicron that we should consider ourselves lucky. There’s another big reason. Our vaccines, with a third shot, are holding up remarkably well. In 2020, the original mRNA vaccines had 95% efficacy vs symptomatic infections at 2 months of follow-up, and a similar efficacy vs hospitalizations and deaths. Now in 2022, with such a substantially distinct strain of the virus, a 3rd shot of mRNA vaccine restores the waned effectiveness across all age groups from 52 to 88%. And also from the United Kingdom Health Security Agency new data that shows in the high risk group of people age 65+, the vaccine effectiveness at 2 months from the booster vs hospitalizations was 94%. The decline at more than 10 weeks was to 89%, which is in keeping with the original vaccine attrition over time. These are of course point estimates and the 95% confidence intervals can be found in the links. Nevertheless, this level of effectiveness of 3-shots of the original vaccine vs Omicron, in consideration of its extensive evolution, is nothing short of extraordinary. And lucky.

If there were enough vaccines for everyone around the world to get the protection equivalent of 3-shots, and people took them, the pandemic would be over now. That’s indeed the unfortunate part—that in countries such as the United States the uptake of vaccination and boosters has been so profoundly disappointing and has even led to anti-vaxxers and many others claiming the vaccines don’t work. When in fact their protection from the biggest challenge we’ve had to date—the strain with the outlier immune escape property—is still quite powerful.

A major explanation for why the vaccines with a 3rd/booster shot have held up so well has little to do with vaccine ingenuity, but rather our immune response, with broadening recognition by our on-demand, memory T cells and specialist B cells, as explained previously.

To recap, the list of luck:

✓ Highly effective and safe vaccines achieved at the highest velocity in history

✓ Omicron has less clinical and experimental severity

✓ A third shot vaccine provides equivalent very high protection vs Omicron as 2-shots did against the original strain vs hospitalizations and severe disease

✓ The human cellular immune response is remarkable

To add to this list, I go back to the development of Paxlovid, the first pill/drug specifically designed to attack SARS-CoV-2. This complex small molecule, which blocks the virus’s main protease and its replication, moved through development to successful placebo-controlled clinical trials in less than 2 years. That, in itself, for a new molecular entity, is parallel to the unprecedented velocity of the success of Covid vaccines. A reminder that most new molecular entities fail in clinical trials—when they work so well and are this safe there’s some element of luck involved. I called it a “just-in-time” breakthrough because, in the context of Omicron, unlike vaccines and monoclonal antibodies, it does not rely on our immune system at all. The problem we have now is its very short supply, which could have been pre-empted had there been large orders made last summer when it wasn’t known whether the drug would work or be safe. Nevertheless, its production and availability will ramp up in the next few months and the drug likely will fulfill its promise as the second most important medical advance after vaccines for the pandemic. For that we also need global pill equity.

We’re all weary and sick of Covid. Omnipresent infections from Omicron have added a rough chapter to this ordeal. But let’s not forget there’s a lot to be thankful for. And that we will eventually prevail over the virus.