How the Science of Aging Can Extend Healthspan

A Time of Optimism for Primary Prevention of the Major Age-Related Diseases

Before getting right into this topic, check out recent related Ground Truths posts which are helpful for background

—The Breakthrough Test for Alzheimer’s

—The Business of Promoting Longevity and Healthspan

—Our Sleep, Brain Aging, and Waste Clearance

—What Can 11,000 Proteins in Our Blood Tell Us

—The Emergence of Protein Organ Clocks

—Exercise May Be the Single Most Potent Medical Intervention Ever Known

As I wrote in Science last year, our ability to do accurate medical forecasting at the individual level is about to take off. While much of the science of aging is focused on reversing aging, the part that has not adequately acknowledged is our newfound capability to precisely and accurately measure the process in a person, not just body-wide (a molecular clock that quantifies the gap between a person’s chronological age vs biological age) but also at the organ level (see the protein organ clocks link above), and temporally (number of years in advance before symptoms develop).

While there are many shots on goal to reverse aging (such as cellular reprogramming, senolytics, rapamycin, rejuvenation of the thymus gland, NAD+, etc), none are proven in people and all carry some risk. In contrast, we have many ways now to prevent the major 3 age-related diseases—cancer, cardiovascular, neurodegenerative. One example, organ clocks for the brain, heart and immune system, will be essential to help guide the way. As you can see from the links at the top of the post, lifestyle factors of diet, sleep and exercise play a critical role in (and there’s much more to that!).

Here’s a gift link to my op-ed in the New York Times today that is a preview to my SUPER AGERS book coming out in 2 weeks.

The full text with some links is below, fact-checked by NYT (which is far more extensive than what is done for medical journal articles)

The dream of reversing aging has captivated humans for centuries, and today science is closer than it ever has been to achieving that goal. Which is to say: It’s still pretty far away.

That’s not for lack of trying. Some researchers are attempting to reprogram cells to make them biologically younger, which has been shown to reverse features of aging in older animals. Unfortunately, this can also induce cancer. Other researchers are studying drugs called senolytics, which aim to clear aging cells out of the body. However, they can also destroy other cells humans need to survive.

Transfusions of blood from young mice appear to rejuvenate older mice, but companies offering this unproven treatment for humans are charging a lot for a potentially dangerous therapy. And while some longevity enthusiasts are taking the drug rapamycin because studies have shown it helps animals live longer, it also weakens the immune system and hasn’t been proved to work in people.

I find these efforts intriguing and worth pursuing. But most people don’t simply want to live until 110. They want to extend the amount of time they live free of serious disease, a concept known as health span. That’s why the most sensible approach is to reduce the toll of three major age-related diseases: cancer, heart disease and neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease. It may be less flashy, but it’s more attainable than ever.

It’s estimated that at least 80 percent of cardiovascular disease cases, 40 percent of cancer cases and 45 percent of Alzheimer’s cases are preventable. Even with a long lag — these diseases can each take 20 years or more to develop — researchers have struggled to accurately define a person’s risk early enough to intervene effectively. Sure, someone can take a genetic test and learn he’s at a heightened risk for Alzheimer’s disease, but what good is that if he doesn’t know whether the disease will emerge early, when he’s 95 or not at all?

In the near future, doctors may not only be able to identify whether a person is at high risk for a serious, age-related disease, they may also be able to predict when that disease is most likely to manifest and how quickly it could progress. Several recent discoveries from the science of aging are making this increasingly possible.

Since the 2000s, scientists have used a person’s genetic sequence to calculate his inherited risk for certain diseases. In just the past five years, the amount of data the medical field can glean about a person’s health on top of that has ballooned. Beyond traditional tools such as medical records, routine lab results and imaging, doctors can draw from a range of biological clocks that help track how the body is aging.

For example, scientists can now measure thousands of proteins from a single vial of blood to generate what are called proteomic organ clocks. These recently discovered clocks can estimate the pace of aging for the brain, heart, liver, kidneys and immune system. These clocks can reveal, for instance, if a person’s heart is aging faster than the rest of her body — like a car mechanic discovering everything is working as it should, except for the rear brakes. Other molecular clocks can calculate a person’s biological age compared to his chronological age. The most rigorously studied one is the so-called epigenetic clock — a reading of parts of our DNA that can be taken from a saliva sample. New blood tests can also detect early signs of the three major diseases linked to aging.

Layering all of this biological information with recent advances in artificial intelligence allows health providers to make increasingly sophisticated predictions about a person’s likelihood of developing a disease.

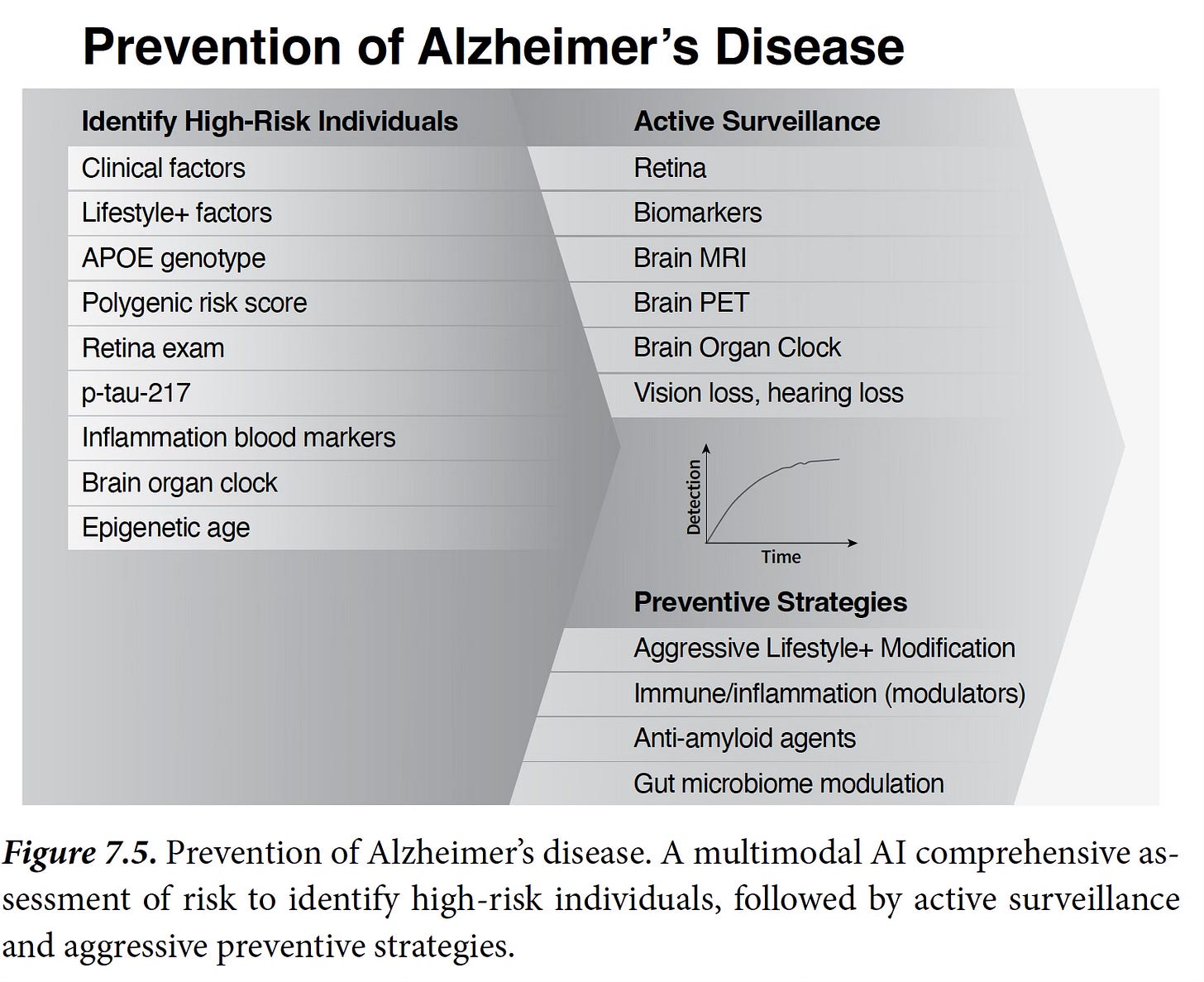

Take a person who wants to determine her risk of Alzheimer’s disease. She can now undergo a blood test for a protein that quantifies plaque buildup in the brain that’s associated with the disease. Soon a doctor might also use a proteomic organ clock to assess whether her brain appears to be aging faster than the rest of her body or analyze a photo of her retina, an emerging tool that, when combined with A.I., can help estimate the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease in the next five to seven years. There are similar tests that can be done to assess cancer and heart disease risk.

This level of insight can usher in a new way to approach such diseases: active surveillance paired with aggressive lifestyle changes. A person deemed at high risk for Alzheimer’s might undergo regular assessments and brain imaging while also taking preventive steps to lower her risk. That could include cutting back on ultra-processed foods, increasing physical activity and addressing any changes to hearing or vision loss — factors that can influence cognitive decline. Doctors could also recommend prioritizing sleep, reducing alcohol and social isolation or getting the shingles vaccine, which has recently been shown to reduce dementia risk. Some might also consider taking GLP-1s, diabetes and weight loss drugs, which appear to reduce harmful inflammation in the brain and body and are being tested in clinical trials to prevent Alzheimer’s.

Pulling together this medical information and turning it into individual plans for preventing chronic diseases is different from today’s approach. Cancer screening protocols, for instance, rely largely on a person’s age. This is also where A.I. models can best benefit medicine. These models are improving in accuracy and reasoning and could one day incorporate data from our gut microbiomes or immune systems to make disease predictions even more precise.

Getting this right will require further study and investment. We don’t want to exacerbate health inequalities by making this kind of medical care accessible only to a wealthy few. The Trump administration’s major reductions in governmental support of medical research will dim these prospects.

Getting an injection of youthful blood or taking the latest trendy anti-aging supplement might seem like a shortcut to a longer life. But extending the years people live without the burden of major age-related diseases is what should be a national priority.

*****************************

Here’s a Figure from the book mapping out the strategy for Alzheimer’s

A Quick Poll

**********************

As you can imagine, I’m excited to get my new book out. I've worked with my publisher, Simon & Schuster, to share an exclusive offer just for Ground Truths subscribers. Through May 5, you can pre-order a hardcover copy of the book at Bookshop.org and get 15% off with code SUPERAGERS15. It’s notable that Bookshop.org supports independent bookstores across the country. Of course there’s also Amazon which currently offers a discount on the book, but it’s certainly not helping these bookstores.

In this post, I’ve only scratched the surface about the content of the book. Here’s the back cover to give you an idea of what some people had to say about it.

Thanks for reading and subscribing to Ground Truths.

If you found this interesting please share it!

That makes the work involved in putting these together especially worthwhile.

All content on Ground Truths—its newsletters, analyses, and podcasts, are free, open-access.

Paid subscriptions are voluntary and all proceeds from them go to support Scripps Research. They do allow for posting comments and questions, which I do my best to respond to. Please don't hesitate to post comments and give me feedback. Many thanks to those who have contributed—they have greatly helped fund our summer internship programs for the past two years.

I appreciate, as always, getting the news you bring on these very promising developments and also being reminded that some straightforward lifestyle choices within one’s own control can be helpful to increase healthspan. Interestingly, though, when responding to your questionnaire, I found the most applicable choice to be “unsure.” This has a good deal to do with my age (76) and the concomitant desire to keep tests and MD appointments to an absolute minimum.

What I see in older friends and am beginning to experience myself is that, as one grows older, interface with the medical establishment can quickly become a hamster wheel one must fight to get off. I hope therefore, as the advances you describe come to fruition, along with that will be some serious thought as to how to deliver the testing and healthcare required in a way that is far less episodic and uncoordinated than it is today. I envision, for example, geriatric health care centers with admin that makes it possible for older people to “one-stop-shop” several routine appointments in a single day. As it is, when I think about the possible need for ongoing tests and visits to monitor a health condition, I want to go running for the exits. But I will definitely continue to take my daily walks and eat a healthy diet inasmuch as is humanly possible!

Hi Dr. Topol,

What if you stop the clocks before age-related issues hit? Or reset them? The key is to find the right targets to do so.

My work (1976-2008) was in characterization of natural products for treating cancers, bio-energetics, and solution protein structure. It was a time where protein structures in the were rare commodities and natural products structures took many months. One set of compounds I worked on in the 80's and 90's were dolastatins and bryostatins. Potent anti-cancer agents but toxic as hell. They also were strong hdac inhibitors.

I morphed into working on the disease Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) in 1998-2006. I have SMA and had to cut my career short in 2006 from my inevitable SMA downward path, some of it cognitive. I've also been on the SMA drugs Spinraza and Evrysdi that came from the early efforts. As a patient/researcher, I've been gotten to experience neuromuscular and cognitive declines and partial reversals in a very personal way.

So, where's the target to stop the aging clock? If you look at the various antibiotics, polyphenols, senolytics, etc., you'll find that the actual target may be the Survival of Motor Neuron Protein (SMN) and SMN genes that cause SMA. Resveratrol, VPA, rapamycin, various polyphenols, EGCG, curcumin all increase SMN expression. SMN has critical roles in rna biogenesis, translation and transcription. SMN is a key protein in axon transport and maintaining motor neurons and neural plates. SMN is increasingly being shown to have multiple tissue-specific roles. SMA offers a wealth of insights for individuals involved in age-related disease. The genetics are complicated (and why we have human brains). I'm outlining how SMN may play a key role in aging in an upcoming conference and followup publication.

For now, I'll leave it at solving the aging issue may be simpler than we think.