Before getting into this new podcast, have you checked out the recent newsletter editions and podcasts of Ground Truths?

—the first diagnostic immunome

—a Covid nasal vaccine update

—medical storytelling and uncertainty

—why did doctors with A.I. get outperformed by A.I. alone?

The audio is available on iTunes and Spotify.

The full video is embedded here, at the top, and also can be found on YouTube.

Transcript with links to Audio and External Links

Eric Topol (00:07):

Well, hello. It's Eric Topol with Ground Truths, and I am just thrilled today to welcome Carl Zimmer, who is one of the great science journalists of our times. He's written 14 books. He writes for the New York Times and many other venues of great science, journalism, and he has a new book, which I absolutely love called Air-Borne. And you can see I have all these rabbit pages tagged and there's lots to talk about here because this book is the book of air. I mean, we're talking about everything that you ever wanted to know about air and where we need to go, how we missed the boat, and Covid and everything else. So welcome, Carl.

Carl Zimmer (00:51):

Thanks so much. Great to be here.

A Book Inspired by the Pandemic

Eric Topol (00:54):

Well, the book starts off with the Skagit Valley Chorale that you and your wife Grace attended a few years later, I guess, in Washington, which is really interesting. And I guess my first question is, it had the look that this whole book was inspired by the pandemic, is that right?

Carl Zimmer (01:18):

Certainly, the seed was planted in the pandemic. I was working as a journalist at the New York Times with a bunch of other reporters at the Times. There were lots of other science writers also just trying to make sense of this totally new disease. And we were talking with scientists who were also trying to make sense of the disease. And so, there was a lot of uncertainty, ambiguity, and things started to come into focus. And I was really puzzled by how hard it was for consensus to emerge about how Covid spread. And I did some reporting along with other people on this conflict about was this something that was spreading on surfaces or was it the word people were using was airborne? And the World Health Organization said, no, it's not airborne, it's not airborne until they said it was airborne. And that just seemed like not quantum physics, you know what I'm saying? In the sense that it seemed like that would be the kind of thing that would get sorted out pretty quickly. And I think that actually more spoke to my own unfamiliarity with the depth of this field. And so, I would talk to experts like say, Donald Milton at the University of Maryland. I'd be like, so help me understand this. How did this happen? And he would say, well, you need to get to know some people like William Wells. And I said, who?

Eric Topol (02:50):

Yeah, yeah, that's what I thought.

Carl Zimmer (02:53):

Yeah, there were just a whole bunch of people from a century ago or more that have been forgotten. They've been lost in history, and yet they were real visionaries, but they were also incredibly embattled. And the question of how we messed up understanding why Covid was airborne turned out to have an answer that took me back thousands of years and really plunged me into this whole science that's known as aerobiology.

Eric Topol (03:26):

Yeah, no, it's striking. And we're going to get, of course, into the Covid story and how it got completely botched as to how it was being transmitted. But of course, as you go through history, you see a lot of the same themes of confusion and naysayers and just extraordinary denialism. But as you said, this goes back thousands of years and perhaps the miasma, the moral stain in the air that was start, this is of course long before there was thing called germ theory. Is that really where the air thing got going?

A Long History of Looking Into Bad Air

Carl Zimmer (04:12):

Well, certainly some of the earliest evidence we have that people were looking at the air and thinking about the air and thinking there's something about the air that matters to us. Aristotle thought, well, there's clearly something important about the air. Life just seems to be revolve around breathing and he didn't know why. And Hippocrates felt that there could be this stain on the air, this corruption of the air, and this could explain why a lot of people in a particular area, young and old, might suddenly all get sick at the same time. And so, he put forward this miasma theory, and there were also people who were looking at farm fields and asking, well, why are all my crops dead suddenly? What happened? And there were explanations that God sends something down to punish us because we've been bad, or even that the air itself had a kind of miasma that affected plants as well as animals. So these ideas were certainly there, well over 2,000 years ago.

Eric Topol (05:22):

Now, as we go fast forward, we're going to get to, of course into the critical work of William and Mildred Wells, who I'd never heard of before until I read your book, I have to say, talk about seven, eight decades filed into oblivion. But before we get to them, because their work was seminal, you really get into the contributions of Louis Pasteur. Maybe you could give us a skinny on what his contributions were because I was unaware of his work and the glaciers, Mer de Glace and figuring out what was going on in the air. So what did he really do to help this field?

Carl Zimmer (06:05):

Yeah, and this is another example of how we can kind of twist and deform history. Louis Pasteur is a household name. People know who Louis Pasteur is. People know about pasteurization of milk. Pasteur is associated with vaccines. Pasteur did other things as well. And he was also perhaps the first aerobiologist because he got interested in the fact that say, in a factory where beet juice was being fermented to make alcohol, sometimes it would spoil. And he was able to determine that there were some, what we know now are bacteria that were getting into the beet juice. And so, it was interrupting the usual fermentation from the yeast. That in itself was a huge discovery. But he was saying, well, wait, so why are there these, what we call bacteria in the spoiled juice? And he thought, well, maybe they just float in the air.

Carl Zimmer (07:08):

And this was really a controversial idea in say, 1860, because even then, there were many people who were persuaded that when you found microorganisms in something, they were the result of spontaneous generation. In other words, the beet juice spontaneously produced this life. This was standard view of how life worked and Pasteur was like, I'm not sure I buy this. And this basically led to him into an incredible series of studies around Paris. He would have a flask, and he'd have a long neck on it, and the flask was full of sterile broth, and he would just take it places and he would just hold it there for a while, and eventually bacteria would fall down that long neck and they would settle in the broth, and they would multiply in there. It would turn cloudy so he could prove that there was life in the air.

Carl Zimmer (08:13):

And they went to different places. He went to farm fields, he went to mountains. And the most amazing trip he took, it was actually to the top of a glacier, which was very difficult, especially for someone like Pasteur, who you get the impression he just hated leaving the lab. This was not a rugged outdoorsman at all. But there he is, climbing around on the ice with this flask raising it over his head, and he caught bacteria there as well. And that actually was pivotal to destroying spontaneous generation as a theory. So aerobiology among many, many other things, destroyed this idea that life could spontaneously burst into existence.

Eric Topol (08:53):

Yeah, no. He says ‘these gentlemen, are the germs of microscopic beings’ shown in the existence of microorganisms in the air. So yeah, amazing contribution. And of course, I wasn't familiar with his work in the air like this, and it was extensive. Another notable figure in the world of germ theory that you bring up in the book with another surprise for me was the great Robert Koch of the Koch postulates. So is it true he never did the third postulate about he never fulfilled his own three postulates?

Carl Zimmer (09:26):

Not quite. Yeah, so he had these ideas about what it would take to actually show that some particular pathogen, a germ, actually caused a disease, and that involved isolating it from patients, culturing it outside of them. And then actually experimentally infecting an animal and showing the symptoms again. And he did that with things like anthrax and tuberculosis. He nailed that. But then when it came to cholera, there was this huge outbreak in Egypt, and people were still battling over what caused cholera. Was it miasma? Was it corruption in the air, or was it as Koch and others believe some type of bacteria? And he found a particular kind of bacteria in the stool of people who were dying or dead of cholera, and he could culture it, and he consistently found it. And when he injected animals with it, it just didn't quite work.

Eric Topol (10:31):

Okay. Yeah, so at least for cholera, the Koch’s third postulate of injecting in animals, reproducing the disease, maybe not was fulfilled. Okay, that's good.

Eric Topol (10:42):

Now, there's a lot of other players here. I mean, with Fred Meier and Charles Lindbergh getting samples in the air from the planes and Carl Flügge. And before we get to the Wells, I just want to mention these naysayers like Charles Chapin, Alex Langmuir, the fact that they said, well, people that were sensitive to pollen, it was just neurosis. It wasn't the pollen. I mean, just amazing stuff. But anyway, the principles of what I got from the book was the Wells, the husband and wife, very interesting characters who eventually even split up, I guess. But can you tell us about their contributions? Because they're really notable when we look back.

William and Mildred Wells

Carl Zimmer (11:26):

Yeah, they really are. And although by the time they had died around 1960, they were pretty much forgotten already. And yet in the 1930s, the two of them, first at Harvard and then at University of Pennsylvania did some incredible work to actually challenge this idea that airborne infection was not anything real, or at least nothing really to worry about. Because once the miasmas have been cleared away, people who embrace the germ theory of disease said, look, we've got cholera in water. We've got yellow fever in mosquitoes. We've got syphilis in sex. We have all these ways that germs can get from one person to the next. We don't need to worry about the air anymore. Relax. And William Wells thought, I don't know if that's true. And we actually invented a new device for actually sampling the air, a very clever kind of centrifuge. And he started to discover, actually, there's a lot of stuff floating around in the air.

Carl Zimmer (12:37):

And then with a medical student of his, Richard Riley started to develop a physical model. How does this happen? Well, you and I are talking, as we are talking we are expelling tiny droplets, and those droplets can potentially contain pathogens. We can sneeze out big droplets or cough them too. Really big droplets might fall to the floor, but lots of other droplets will float. They might be pushed along by our breath like in a cloud, or they just may be so light, they just resist gravity. And so, this was the basic idea that he put forward. And then he made real headlines by saying, well, maybe there's something that we can do to these germs while they're still in the air to protect our own health. In the same way you'd protect water so that you don't get cholera. And he stumbled on ultraviolet light. So basically, you could totally knock out influenza and a bunch of other pathogens just by hitting these droplets in the air with light. And so, the Wells, they were very difficult to work with. They got thrown out of Harvard. Fortunately, they got hired at Penn, and they lasted there just long enough that they could run an experiment in some schools around Philadelphia. And they put up ultraviolet lamps in the classrooms. And those kids did not get hit by huge measles outbreak that swept through Philadelphia not long afterwards.

Eric Topol (14:05):

Yeah, it's pretty amazing. I had never heard of them. And here they were prescient. They did the experiments. They had this infection machine where they could put the animal in and blow in the air, and it was basically like the Koch's third postulate here of inducing the illness. He wrote a book, William and he’s a pretty confident fellow quoted, ‘the book is not for here and now. It is from now on.’ So he wasn't a really kind of a soft character. He was pretty strong, I guess. Do you think his kind of personality and all the difficulties that he and his wife had contributed to why their legacy was forgotten by most?

Carl Zimmer (14:52):

Yes. They were incredibly difficult to work with, and there's no biography of the Wellses. So I had to go into archives and find letters and unpublished documents and memos, and people will just say like, oh my goodness, these people are so unbearable. They just were fighting all the time. They were fighting with each other. They were peculiar, particularly William was terrible with language and just people couldn't deal with them. So because they were in these constant fights, they had very few friends. And when you have a big consensus against you and you don't have very many friends to not even to help you keep a job, it's not going to turn out well, unfortunately. They did themselves no favors, but it is still really remarkable and sad just how much they figured out, which was then dismissed and forgotten.

Eric Topol (15:53):

Yeah, I mean, I'm just amazed by it because it's telling about your legacy in science. You want to have friends, you want to be, I think, received well by your colleagues in your community. And when you're not, you could get buried, your work could get buried. And it kind of was until, for me, at least, your book Air-Borne. Now we go from that time, which is 60, 70 years ago, to fast forward H1N1 with Linsey Marr from Virginia Tech, who in 2009 was already looking back at the Wells work and saying, wait a minute there's something here that this doesn't compute, kind of thing. Can you give us the summary about Linsey? Of course, we're going to go to 2018 again all before the pandemic with Lydia, but let's first talk about Linsey.

Linsey Marr

See my previous Ground Truths podcast with Prof Marr here

Carl Zimmer (16:52):

Sure. So Linsey Marr belongs to this new generation of scientists in the 21st century who start to individually rediscover the Welles. And then in Lind\sey Marr's case, she was studying air pollution. She's an atmospheric scientist and she's at Virginia Tech. And she and her husband are trying to juggle their jobs and raising a little kid, and their son is constantly coming home from daycare because he's constantly getting sick, or there's a bunch of kids who are sick there and so on. And that got Linsey Marr actually really curious like what's going on because they were being careful about washing objects and so on, and doing their best to keep the kids healthy. And she started looking into ideas about transmission of diseases. And she got very interested in the flu because in 2009, there was a new pandemic, in other words that you had this new strain of influenza surging throughout the world. And so, she said, well, let me look at what people are saying. And as soon as she started looking at it, she just said, well, people are saying things that as a physicist I know make no sense. They're saying that droplets bigger than five microns just plummet to the ground.

Carl Zimmer (18:21):

And in a way that was part of a sort of a general rejection of airborne transmission. And she said, look, I teach this every year. I just go to the blackboard and derive a formula to show that particles much bigger than this can stay airborne. So there's something really wrong here. And she started spending more and more time studying airborne disease, and she kept seeing the Welles as being cited. And she was like, who are these? Didn't know who they were. And she had to dig back because finding his book is not easy, I will tell you that. You can't buy it on Amazon. It's like it was a total flop.

Eric Topol (18:59):

Wow.

Carl Zimmer (19:00):

And eventually she started reading his papers and getting deeper in it, and she was like, huh. He was pretty smart. And he didn't say any of the things that people today are claiming he said. There's a big disconnect here. And that led her into join a very small group of people who really were taking the idea of airborne infection seriously, in the early 2000s.

Lydia Bourouiba

Eric Topol (19:24):

Yeah, I mean, it's pretty incredible because had we listened to her early on in the pandemic and many others that we're going to get into, this wouldn't have gone years of neglect of airborne transmission of Covid. Now, in 2018, there was, I guess, a really important TEDMED talk by Lydia. I don't know how you pronounce her last name, Bourouiba or something. Oh, yeah. And she basically presented graphically. Of course, all this stuff is more strained for people to believe because of the invisibility story, but she, I guess, gave demos that were highly convincing to her audience if only more people were in her audience. Right?

Carl Zimmer (20:09):

That's right. That's right. Yeah. So Lydia was, again, not an infectious disease expert at first. She was actually trained as a physicist. She studied turbulence like what you get in spinning galaxies or spinning water in a bathtub as it goes down the drain. But she was very taken aback by the SARS outbreak in 2003, which did hit Canada where she was a student.

Carl Zimmer (20:40):

And it really got her getting interested in infectious diseases, emerging diseases, and asking herself, what tools can I bring from physics to this? And she's looked into a lot of different things, and she came to MIT and MIT is where Harold Edgerton built those magnificent stroboscope cameras. And we've all seen these stroboscope images of the droplets of milk frozen in space, or a bullet going through a card or things like that that he made in the 1930s and 1940s and so on. Well, one of the really famous images that was used by those cameras was a sneeze actually, around 1940. That was the first time many Americans would see these droplets frozen in space. Of course, they forgot them.

Carl Zimmer (21:34):

So she comes there and there's a whole center set up for this kind of high-speed visualization, and she starts playing with these cameras, and she starts doing experiments with things like breathing and sneezes and so on. But now she's using digital video, and she discovers that she goes and looks at William Wells and stuff. She's like, that's pretty good, but it's pretty simple. It's pretty crude. I mean, of course it is. It was in the 1930s. So she brings a whole new sophistication of physics to studying these things, which she finds that, especially with a sneeze, it sort of creates a new kind of physics. So you actually have a cloud that just shoots forward, and it even carries the bigger droplets with it. And it doesn't just go three feet and drop. In her studies looking at her video, it could go 10 feet, 20 feet, it could just keep going.

Eric Topol (22:24):

27 feet, I think I saw. Yeah, right.

Carl Zimmer (22:26):

Yeah. It just keeps on going. And so, in 2018, she gets up and at one of these TEDMED talks and gives this very impressive talk with lots of pictures. And I would say the world didn't really listen.

Eric Topol (22:48):

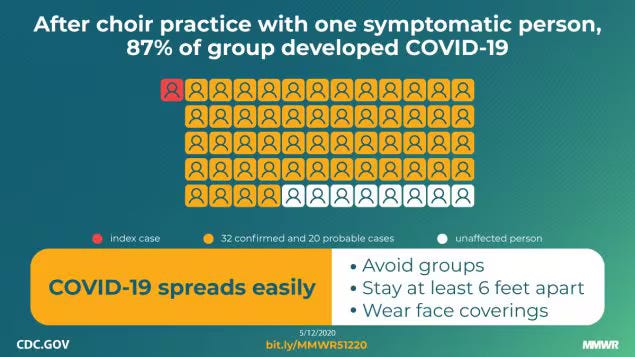

Geez and amazing. Now, the case that you, I think centered on to show how stupid we were, not everyone, not this group of 36, we're going to talk about not everyone, but the rest of the world, like the WHO and the CDC and others was this choir, the Skagit Valley Chorale in Washington state. Now, this was in March 2020 early on in the pandemic, there were 61 people exposed to one symptomatic person, and 52 were hit with Covid. 52 out of 61, only 8 didn't get Covid. 87% attack rate eventually was written up by an MMWR report that we'll link to. This is extraordinary because it defied the idea of that it could only be liquid droplets. So why couldn't this early event, which was so extraordinary, opened up people's mind that there's not this six-foot rule and it’s all these liquid droplets and the rest of the whole story that was wrong.

Carl Zimmer (24:10):

I think there's a whole world of psychological research to be done on why people accept or don't accept scientific research and I'm not just talking about the public. This is a question about how science itself works, because there were lots of scientists who looked at the claims that Linsey Marr and others made about the Skagit Valley Chorale outbreak and said, I don't know, I'm not convinced. You didn't culture viable virus from the air. How do you really know? Really, people have said that in print. So it does raise the question of a deep question, I think about how does science judge what the right standard of proof is to interpret things like how diseases spread and also how to set public health policy. But you're certainly right that and March 10th, there was this outbreak, and by the end of March, it had started to make news and because the public health workers were figuring out all the people who were sick and so on, and people like Linsey Marr were like, this kind of looks like airborne to me, but they wanted to do a closer study of it. But still at that same time, places like the World Health Organization (WHO) were really insisting Covid is not airborne.

“This is so mind-boggling to me. It just made it obvious that they [WHO] were full of shit.”—Jose-Luis Jimenez

Getting It Wrong, Terribly Wrong

Eric Topol (25:56):

It's amazing. I mean, one of the quotes that there was, another one grabbed me in the book, in that group of the people that did air research understanding this whole field, the leaders, there's a fellow Jose-Luis Jimenez from University of Colorado Boulder, he said, ‘this is so mind-boggling to me. It just made it obvious that they were full of shit.’ Now, that's basically what he's saying about these people that are holding onto this liquid droplet crap and that there's no airborne. But we know, for example, when you can't see cigarette smoke, you can't see the perfume odor, but you can smell it that there's stuff in the air, it's airborne, and it's not necessarily three or six feet away. There's something here that doesn't compute in people's minds. And by the way, even by March and April, there were videos like the one that Lydia showed in 2018 that we're circling around to show, hey, this stuff is all over the place. It's not just the mouth going to the other person. So then this group of 36 got together, which included the people we were talking about, other people who I know, like Joe Allen and many really great contributors, and they lobbied the CDC and the WHO to get with it, but it seemed like it took two years.

Carl Zimmer (27:32):

It was a slow process, yes. Yes. Because well, I mean, the reason that they got together and sort of formed this band is because early on, even at the end of January, beginning of February 2020, people like Joe Allen, people like Linsey Marr, people like Lidia Morawska in Australia, they were trying to raise the alarm. And so, they would say like, oh, I will write up my concerns and I will get it published somewhere. And journals would reject them and reject them and reject them. They'd say, well, we know this isn't true. Or they'd say like, oh, they're already looking into it. Don't worry about it. This is not a reason for concern. All of them independently kept getting rejected. And then at the same time, the World Health Organization was going out of their way to insist that Covid is not airborne. And so, Lidia Morawska just said like, we have to do something. And she, from her home in Australia, marshaled first this group of 36 people, and they tried to get the World Health Organization to listen to them, and they really felt very rebuffed it didn't really work out. So then they went public with a very strong open letter. And the New York Times and other publications covered that and that really started to get things moving. But still, these guidelines and so on were incredibly slow to be updated, let alone what people might actually do to sort of safeguard us from an airborne disease.

Eric Topol (29:15):

Well, yeah, I mean, we went from March 2020 when it was Captain Obvious with the choir to the end of 2021 with Omicron before this got recognized, which is amazing to me when you look back, right? That here you've got millions of people dying and getting infected, getting Long Covid, all this stuff, and we have this denial of what is the real way of transmission. Now, this was not just a science conflict, this is that we had people saying, you don't need to wear a mask. People like Jerome Adams, the Surgeon General, people like Tony Fauci before there was an adjustment later, oh, you don't need masks. You just stay more than six feet away. And meanwhile, the other parts of the world, as you pointed out in Japan with the three Cs, they're already into, hey, this is airborne and don't go into rooms indoors with a lot of people and clusters and whatnot. How could we be this far off where the leading public health, and this includes the CDC, are giving such bad guidance that basically was promoting Covid spread.

Carl Zimmer (30:30):

I think there are a number of different reasons, and I've tried to figure that out, and I've talked to people like Anthony Fauci to try to better understand what was going on. And there was a lot of ambiguity at the time and a lot of mixed signals. I think that also in the United States in particular, we were dealing with a really bad history of preparing for pandemics in the sense that the United States actually had said, we might need a lot of masks for a pandemic, which implicitly means that we acknowledge that the next pandemic might to some extent be airborne. At least our healthcare folks are going to need masks, good masks, and they stockpiled them, and then they started using them, and then they didn't really replace them very well, and supplies ran out, or they got old. So you had someone like Rick Bright who was a public health official in the administration in January 2020, trying to tell everybody, hey, we need masks.

The Mess with Masks

Carl Zimmer (31:56):

And people are like, don't worry about it, don't worry about it. Look, if we have a problem with masks, he said this, and he recounted this later. Look, if the health workers run out of masks, we just tell the public just to not use masks and then we'll have enough for the health workers. And Bright was like, that makes no sense. That makes no sense. And lo and behold, there was a shortage among American health workers, and China was having its own health surge, so they were going to be helping us out, and it was chaos. And so, a lot of those messages about telling the public don't wear a mask was don't wear a mask, the healthcare workers need them, and we need to make sure they have enough. And if you think about that, there's a problem there.

Carl Zimmer (32:51):

Yeah, fine. Why don't the healthcare workers have their own independent supply of masks? And then we can sort of address the question, do masks work in the general community? Which is a legitimate scientific question. I know there are people who are say, oh, masks don't work. There's plenty of studies that show that they can reduce risk. But unfortunately, you actually had people like Fauci himself who were saying like, oh, you might see people wearing masks in other countries. I wouldn't do it. And then just a few weeks later when it was really clear just how bad things were getting, he turns around and says, people should wear masks. But Jerome Adams, who you mentioned, Surgeon General, he gets on TV and he's trying to wrap a cloth around his face and saying, look, you can make your own mask. And it was not ideal, shall we say?

Eric Topol (33:55):

Oh, no. It just led to mass confusion and the anti-science people were having just a field day for them to say that these are nincompoops. And it just really, when you look back, it's sad. Now, I didn't realize the history of the N95 speaking of healthcare workers and fitted masks, and that was back with the fashion from the bra. I mean, can you tell us about that? That's pretty interesting.

Carl Zimmer (34:24):

Yeah. Yeah, it's a fascinating story. So there was a woman who was working for 3M. She was consulting with them on just making new products, and she really liked the technology they used for making these sort of gift ribbons and sort of blown-fiber. And she's like, wow, you should think about other stuff. How about a bra? And so, they actually went forward with this sort of sprayed polyester fiber bra, which was getting much nicer than the kind of medieval stuff that women had to put up with before then. And then she's at the same time spending a lot of time in hospitals because a lot of her family was sick with various ailments, and she was looking at these doctors and nurses who were wearing masks, which just weren't fitting them very well. And she thought, wait a minute, you could take a bra cup and just basically fit it on people's faces.

Carl Zimmer (35:29):

She goes to 3M and is like, hey, what about this? And they're like, hmm, interesting. And at first it didn't seem actually like it worked well against viruses and other pathogens, but it was good on dust. So it started showing up in hardware stores in the 70s, and then there were further experiments that basically figured showed you could essentially kind of amazingly give the material a little static charge. And that was good enough that then if you put it on, it traps droplets that contain viruses and doesn't let them through. So N95s are a really good way to keep viruses from coming into your mouth or going out.

Eric Topol (36:14):

Yeah. Well, I mean it's striking too, because in the beginning, as you said, when there finally was some consensus that masks could help, there wasn't differentiation between cotton masks, surgical masks, KN95s. And so, all this added to the mix of ambiguity and confusion. So we get to the point finally that we understand the transmission. It took way too long. And that kind of tells the Covid story. And towards the end of the book, you're back at the Skagit Valley Chorale. It's a full circle, just amazing story. Now, it also brings up all lessons that we've learned and where we're headed with this whole knowledge of the aerobiome, which is fascinating. I didn't know that we breathe 2000 to 3000 gallons a day of air, each of us.

Every Breath We Take

Eric Topol (37:11):

Wow, I didn't know. Well, of course, air is a vector for disease. And of course, going back to the Wells, the famous Wells that have been, you've brought them back to light about how we're aerial oysters. So these things in the air, which we're going to get to the California fires, for example, they travel a long ways. Right? We're not talking about six feet here. We're talking about, can you tell us a bit about that?

Carl Zimmer (37:42):

Well, yeah. So we are releasing living things into the air with every breath, but we're not the only ones. So I'm looking at you and I see beyond you the ocean and the Pacific Ocean. Every time those waves crash down on the surf, it's spewing up vast numbers of tiny droplets, kind of like the ocean's own lungs, spraying up droplets, some of which have bacteria and viruses and other living things. And those go up in the air. The wind catches them, and they blow around. Some of them go very, very high, many, many miles. Some of them go into the clouds and they do blow all over the place. And so, science is really starting to come into its own of studying the planetary wide pattern of the flow of life, not just for oceans, but from the ground, things come out of the ground all of the time. The soil is rich with microbes, and those are rising up. Of course, there’s plants, we are familiar with plants having pollen, but plants themselves are also slathered in fungi and other organisms. They shed those into the air as well. And so, you just have this tremendous swirl of life that how high it can go, nobody's quite sure. They can certainly go up maybe 12 miles, some expeditions, rocket emissions have claimed to find them 40 miles in the air.

Carl Zimmer (39:31):

It's not clear, but we're talking 10, 20, 30 miles up is where all this life gets. So people call this the aerobiome, and we're living in it. It's like we're in an ocean and we're breathing in that ocean. And so, you are breathing in some of those organisms literally with every breath.

Eric Topol (39:50):

Yeah, no, it's extraordinary. I mean, it really widens, the book takes us so much more broad than the narrow world of Covid and how that got all off track and gives us the big picture. One of the things that happened more recently post Covid was finally in the US there was the commitment to make buildings safer. That is adopting the principles of ventilation filtration. And I wonder if you could comment at that. And also, do you use your CO2 monitor that you mentioned early in the book? Because a lot of people haven't gotten onto the CO2 monitor.

Carl Zimmer (40:33):

So yes, I do have a CO2 monitor. It's in the other room. And I take it with me partly to protect my own health, but also partly out of curiosity because carbon dioxide (CO2) in the room is actually a pretty good way of figuring out how much ventilation there is in the room and what your potential risk is of getting sick if someone is breathing out Covid or some other airborne disease. They're not that expensive and they're not that big. And taking them on planes is particularly illuminating. It's just incredible just how high the carbon dioxide rate goes up when you're sitting on the plane, they've closed the doors, you haven't taken off yet, shoots way up. Once again, the air and the filter system starts up, it starts going down, which is good, but then you land and back up again. But in terms of when we're not flying, we're spending a lot of our time indoors. Yeah, so you used the word commitment to describe quality standards.

Eric Topol (41:38):

What's missing is the money and the action, right?

Carl Zimmer (41:42):

I think, yeah. I think commitment is putting it a little strongly.

Eric Topol (41:45):

Yeah. Sorry.

Carl Zimmer (41:45):

Biden administration is setting targets. They're encouraging that that people meet certain targets. And those people you mentioned like Joe Allen at Harvard have actually been putting together standards like saying, okay, let's say that when you build a new school or a new building, let's say that you make sure that you don't get carbon dioxide readings above this rate. Let's try to get 14 liters per second per person of ventilated fresh air. And they're actually going further. They've actually said, now we think this should be law. We think these should be government mandates. We have government mandates for clean water. We have government mandates for clean food. We don't just say, it'd be nice if your bottled water didn't have cholera on it in it. We'll make a little prize. Who's got the least cholera in their water? We don't do that. We don't expect that. We expect more. We expect when you get the water or if you get anything, you expect it to be clean and you expect people to be following the law. So what Joseph Allen, Lidia Morawska, Linsey Marr and others are saying is like, okay, let's have a law.

Eric Topol (43:13):

Yeah. No, and I think that distinction, I've interviewed Joe Allen and Linsey Marr on Ground Truths, and they've made these points. And we need the commitment, I should say, we need the law because otherwise it's a good idea that doesn't get actualized. And we know how much keeping ventilation would make schools safer.

Carl Zimmer (43:35):

Just to jump in for a second, just to circle back to William and Mildred Wells, none of what I just said is new. William and Mildred Wells were saying over and over again in speeches they gave, in letters they wrote to friends they were like, we've had this incredible revolution in the early 1900s of getting clean water and clean food. Why don't we have clean air yet? We deserve clean air. Everyone deserves clean air. And so, really all that people like Linsey Marr and Joseph Allen and others are doing is trying to finally deliver on that call almost a century later.

Eric Topol (44:17):

Yeah, totally. That's amazing how it's taken all this time and how much disease and morbidity even death could have been prevented. Before I ask about planning for the future, I do want to get your comments about the dirty air with the particulate matter less than 2.5 particles and what we're seeing now with wildfires, of course in Los Angeles, but obviously they're just part of what we're seeing in many parts of the world and what that does, what carries so the dirty air, but also what we're now seeing with the crisis of climate change.

Carl Zimmer (45:01):

So if you inhale smoke from a wildfire, it's not going to start growing inside of you, but those particles are going to cause a lot of damage. They're going to cause a lot of inflammation. They can cause not just lung damage, but they can potentially cause a bunch of other medical issues. And unfortunately, climate change plus the increasing urbanization of these kinds of environments, like in Southern California where fires, it's a fire ecology already. That is going to be a recipe for more smoke in the air. We will be, unfortunately, seeing more fire. Here in the Northeast, we were dealing with really awful smoke coming all the way from Canada. So this is not a problem that respects borders. And even if there were no wildfires, we still have a huge global, terrible problem with particulate matter coming from cars and coal fire power plants and so on. Several million people, their lives are cut short every year, just day in, day out. And you can see pictures in places like Delhi and India and so on. But there are lots of avoidable deaths in the United States as well, because we're starting to realize that even what we thought were nice low levels of air pollution probably are still killing more people than we realized.

Eric Topol (46:53):

Yeah, I mean, just this week in Nature is a feature on how this dirty air pollution, the urbanization that’s leading to brain damage, Alzheimer’s, but also as you pointed out, it increases everything, all-cause mortality, cardiovascular, various cancers. I mean, it's just bad news.

Carl Zimmer (47:15):

And one way in which the aerobiome intersects with what we're talking about is that those little particles floating around, things can live on them and certain species can ride along on these little particles of pollution and then we inhale them. And there's some studies that seem to suggest that maybe pathogens are really benefiting from riding around on these. And also, the wildfire smoke is not just lofting, just bits of dead plant matter into the air. It's lofting vast numbers of bacteria and fungal spores into the air as well. And then those blow very, very far away. It's possible that long distance winds can deliver fungal spores and other microorganisms that can actually cause certain diseases, this Kawasaki disease or Valley fever and so on. Yeah, so everything we're doing is influencing the aerobiome. We're changing the world in so many ways. We're also changing the aerobiome.

Eric Topol (48:30):

Yeah. And to your point, there were several reports during the pandemic that air pollution potentiated SARS-CoV-2 infections because of that point that you're making that is as a carrier.

Carl Zimmer (48:46):

Well, I've seen some of those studies and it wasn't clear to me. I'm not sure that SARS-CoV-2 can really survive like long distances outdoors. But it may be that, it kind of weakens people and also sets up their lungs for a serious disease. I'm not as familiar with that research as I'd like to be.

Eric Topol (49:11):

Yeah, no, it could just be that because they have more inflammation of their lungs that they're just more sensitive to when they get the infection. But there seems like you said, to be some interactions between pathogens and polluted air. I don't know that we want to get into germ warfare because that's whole another topic, but you cover that well, it's very scary stuff.

Carl Zimmer (49:37):

It’s the dark side of aerobiology.

Eric Topol (49:39):

Oh my gosh, yes. And then the last thing I wanted just to get into is, if we took this all seriously and learned, which we don't seem to do that well in some respects, wouldn’t we change the way, for example, the way our cities, the way we increase our world of plants and vegetation, rather than just basically take it all down. What can we do in the future to make our ecosystem with air a healthier one?

Carl Zimmer (50:17):

I think that's a really important question. And it sounds odd, but that's only because it's unfamiliar. And even after all this time and after the rediscovery of a lot of scientists who had been long forgotten, there's still a lot we don't know. So there is suggestive research that when we breathe in air that's blowing over vegetation, forest and so on. That's actually in some ways good for our health. We do have a relationship with the air, and we've had it ever since our ancestors came out the water and started breathing with their lungs. And so, our immune systems may be tuned to not breathing in sterile air, but we don't understand the relationship. And so, I can't say like, oh, well, here's the prescription. We need to be doing this. We don't know.

Eric Topol (51:21):

Yeah. No, it's fascinating.

Carl Zimmer (51:23):

We should find out. And there are a few studies going on, but not many I would have to say. And the thing goes for how do we protect indoor spaces and so on? Well, we kind of have an idea of how airborne Covid is. Influenza, we're not that sure and there are lots of other diseases that we just don't know. And you certainly, if a disease is not traveling through the air at all, you don't want to take these measures. But we need to understand they're spread more and it's still very difficult to study these things.

Eric Topol (52:00):

Yeah, such a great point. Now before we wrap up, is there anything that you want to highlight that I haven't touched on in this amazing book?

Carl Zimmer (52:14):

I hope that when people read it, they sort of see that science is a messy process and there aren't that many clear villains and good guys in the sense that there can be people who are totally, almost insanely wrong in hindsight about some things and are brilliant visionaries in other ways. And one figure that I learned about was Max von Pettenkofer, who really did the research behind those carbon dioxide meters. He figured out in the mid-1800s that you could figure out the ventilation in a room by looking at the carbon dioxide. We call it the Pettenkofer number, how much CO2 is in the room. Visionary guy also totally refused to believe in the germ theory of disease. He shot it tooth in the nail even. He tried to convince people that cholera was airborne, and he did it. He took a vial. He was an old man. He took a vial full of cholera. The bacteria that caused cholera drank it down to prove his point. He didn't feel well afterwards, but he survived. And he said, that's proof. So this history of science is not the simple story that we imagine it to be.

Eric Topol (53:32):

Yeah. Well, congratulations. This was a tour de force. You had to put in a lot of work to pull this all together, and you're enlightening us about air like never before. So thanks so much for joining, Carl.

Carl Zimmer (53:46):

It was a real pleasure. Thanks for having me.

**********************************************

Thanks for listening, watching or reading Ground Truths. Your subscription is greatly appreciated.

If you found this podcast interesting please share it!

That makes the work involved in putting these together especially worthwhile.

All content on Ground Truths—newsletters, analyses, and podcasts—is free, open-access.

Paid subscriptions are voluntary and all proceeds from them go to support Scripps Research. They do allow for posting comments and questions, which I do my best to respond to. Many thanks to those who have contributed—they have greatly helped fund our summer internship programs for the past two years. And such support is becoming more vital In light of current changes of funding by US biomedical research at NIH and other governmental agencies.

Share this post